What is wrong with Performance Measurement?

smartKPIs.com Performance Architect update 19/2010

A simple answer is over-reliance on measurement and its merits.

Since ancient times, humans had a fascination with measurement. In discovering the natural universe, measurement has its merits and one might say it is indispensable. Evaluating the physical properties of the world around us, we have gradually developed a rather objective and accurate way to determine distance, weight, density among others.

In administrative science things are different, tough. Measurement is done by humans and results are used by humans in a much more subjective environment, conducive of errors. It is not something new, and it will not be easily addressed, if ever.

Protagoras of Abdera, who lived between 480-410 B.C. famously said: “Man is the measure of all things”. His words have deep philosophical meanings that reverberate deeply in a performance measurement context. The implications are on one hand at a practical level, as ancient Greek measurement systems used in construction and architecture were based on the dimensions of the human body. On the other hand, at conceptual level, it underpins some of the human evaluation dilemmas that has been in place for centuries.

A relevant example of this dilemma is the practice of conducting individual performance evaluation. The precise origin of performance appraisals is not known but the practice dates back to the third century when the emperors of the Wei Dynasty (221-265AD) rated the performance of the official family members (Banner & Cooke (1984); Coens and Jenkins (2000)). Fairness of raters was questioned since the third century by the Chinese philosopher Sin Yu who reportedly criticized a rater employed by the Wei Dynasty with the following words: “The Imperial Rater of Nine Grade seldom rates men according to their merits, but always according to his likes and dislikes” (Patten (1977) as cited in Banner & Cooke (1984)).

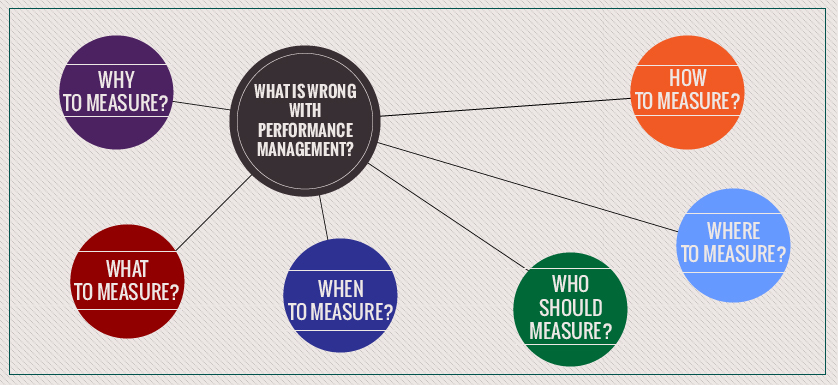

Fast forward a few hundred years and at the turn of the 20th century a performance measurement revolution is announced and driven by Harvard Business School researchers. Eccles published his famous manifesto on 1991 and Kaplan and Norton seized the opportunity to give the world the tool to drive change, fueling it with an equally famous article in 1992 that promoted the Balanced Scorecard as a performance measurement tool. They have quickly realized that measurement is not the key and shifted their efforts towards strategy and performance measurement overall. However, as a result of the growing popularity of the Balanced Scorecard as a strategic performance management system, the efforts of many researchers and practitioners focused on the measurement side of things, trusting that performance management is taken care of. Thousands of articles and books on performance measurement were written in the 90s, many addressing questions such as:

- Why to measure?

- What to measure?

- When to measure?

- Who should measure?

- Where to measure?

- How to measure?

By the beginning of the 21st century, the attitude towards Performance Measurement as a discipline was similar to the one towards Physics a century ago, when Lord Kelvin said: “There is nothing new to be discovered in physics now. All that remains is more and more precise measurement.”

Fueled by advanced in technology, accelerated rate of change in the environment in which many organizations operate and the enthusiastic momentum of the 90s, performance measurement continued dominate the Performance Management research and practice agenda. The fascination of the measurement promise is similar to the one in Physics. There seems to be an attitude that there is nothing new to be discovered in Performance Management now. All that remains is more and more precise performance measurement. As in Physics this view is far from being accurate. There are two major flows with is:

- It is not the data that matters, but what you do with it and the impact. Having a very accurate set of data that is used incorrectly and leads to the wrong decisions is worse than having a less accurate set of data, but used smartly in leading to the correct decisions.

- We should not discount the possibility that data accuracy in human administration is an elusive desideratum. Coming back to Physics, Nield Bohr’s statement gives food for thought: “Accuracy and clarity of statement are mutually exclusive”.

One of today’s tragedies provides the scene to put things into context. We might never know exactly the amount of oil that leaked in the Gulf of Mexico as a result of the The Deepwater Horizon incident. What matters more is not the exact quantities and linking them to bonuses for cleaning or penalties for the accident taking place. Learning the right lessons from such an incident, changing attitudes and behaviors and making a positive impact on both recovery efforts and the future operations of the company, response teams, the industry, local community and the regulators is what matters.

Performance measurement puts too much value on measurement. And as Benjamin Franklin once said “I conceive that the great part of the miseries of mankind are brought upon them by false estimates they have made of the value of things.”

Stay smart! Enjoy smartKPIs.com!

Aurel Brudan

Performance Architect, www.smartKPIs.com

References

- Banner, D.K., & Cooke, R.A. (1984). Ethical dilemmas in performance appraisal. Journal of Business Ethics, No. 3, pp. 327-333.

- Coens,T., & Jenkins, M. (2000). Abolishing performance appraisals: why they backfire and what to do instead. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers

- Eccles, R.G. 1991, “The performance measurement manifesto”, Harvard Business Review, Vol 69, No.1 January-February, pp. 131-137.

- Kaplan, R. S. and Norton D. P. (1992, Jan-Feb) ‘The Balanced Scorecard – Measures That Drive Performance’, Harvard Business Review, Vol.70, No.1, pp.71-79

- Patten, T.H., Jr (1977), Pay: Employee Compensation and Incentive Plans, pp. 352 Free Press, London.

Tags: Aurel Brudan, Performance Architect Update, Performance Measurement, Theory