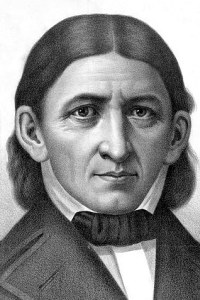

Fröbel, Friedrich (1782–1852)

Article by Helmut Heiland

In his main work entitled Die Menschenerziehung [On the education of man, (1826)], Fröbel defined his pedagogical principles, which owe much to neo-humanist educational theory, in the following words:

In his main work entitled Die Menschenerziehung [On the education of man, (1826)], Fröbel defined his pedagogical principles, which owe much to neo-humanist educational theory, in the following words:

The divine, God, is omnipresent; His influence governs all things […] which have their being only by reason of the divine principle active in them. The divine principle active in all things constitutes their very essence. The purpose and vocation of all things is to develop their essence which is their divine nature and the divine principle per se, in such a way that God is proclaimed and revealed through their external and transient manifestations. The special purpose and particular vocation of man as a sentient and reasoning being is to bring his own essence, his divine nature and through it God, His intended purpose and vocation, to complete consciousness that they may become a clearly perceived living reality which is exercised and proclaimed through the life of the individual. The purpose of education is to encourage and guide man as a conscious, thinking and perceiving being in such a way that he becomes a pure and perfect representation of that divine inner law through his own personal choice; education must show him the ways and means of attaining that goal (Fröbel, 1826, p. 2 et seq.).

This educational theory is also the foundation of Fröbel’s ‘kindergarten’ which has gained worldwide recognition and lies at the heart of his international reputation. However, Fröbel also applied his concept of education to schools and put his ideas into practice in his own private school, the General German Educational Establishment at Keilhau near Rudolstadt in the environs of Weimar. Fröbel’s kindergarten pedagogics are still the subject of intense discussion today, especially in the United Kingdom and Japan. His play materials, ‘gifts’ and ‘occupations’ spread throughout the world in the nineteenth century. Alongside Montessori’s didactic materials for young children, they represent the most effective and comprehensive programme for teaching 3- to 6-year old children through play.

Childhood and youth

Friedrich Wilhelm August Fröbel was born on 21 April 1782 at Oberweissbach in the Thuringian principality of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt as the sixth child of a pastor. His mother died six months later from the secondary effects of this difficult childbirth. Little Friedrich was left to his own devices. His stepmother—his father married again in 1785—took no interest in him. Fröbel was to speak later of the ‘awful dawn of my early life’ (Lange, 1862, p. 37). The neglect he suffered was later reflected in his defiant and egocentric attitudes. His father formed the impression that little Fritz was a ‘wicked’ child with limited intellectual abilities. His father obliged him to attend church services, but always on his own, locked up in the sacristy. And so Friedrich Fröbel, who pondered on the meaning of the words of the Bible and the riddles of nature as he wandered through the forests and meadows of his native region, went on to adopt the attitudes of a self-taught adult:

‘Unlimited self-observation, self-contemplation and self-education were the basic features of my life from an early age’ (Lange, 1862, p. 38). He acquired an observant and analyzing relationship with nature:

Memories from my youth: gazing at tulips with unutterable delight. Intense pleasure in their regular forms. Thestriking pattern of the six petals and the three-edged seed pods […] Joyful contemplation of the hazel catkin with itsdelightful colours; pleasure in lime blossom. All their caring and loving traits filled me with awe. Dissecting beans atOberweissbach in the hope of finding an explanation (Kuntze, 1952, p. 13).

Fröbel’s childhood and early youth were marked by the loss of his mother, his love of nature and Christian faith. These aspects went on to influence the rest of his life: his educational theory has a Christian, but undogmatic foundation; the games which are part of his pedagogical theory for kindergarten stress the togetherness of adults and children at play, but also the self-educating function of materials or ‘natural objects’ whose structures and laws are revealed. Throughout his life, Friedrich Fröbel, the educationalist, took a sustained interest in natural scientific knowledge, especially in the disciplines of mineralogy and crystallography.

After attending the elementary school in Oberweissbach, his uncle, estate superintendent Hoffmann, took him into his home at Stadtilm. Here Fröbel attended the municipal elementary school. His formal education ended with his confirmation in 1796 that left a very deep impression on him and strengthened his religious conviction. Fröbel did not go on to a course of higher education. His father still believed him to be unintelligent and felt that a practical career would be preferable. He began training as a surveyor with a forester, but gave up after only two years (1799). Fröbel was given an ‘altogether unsatisfactory report’ (Lange, 1862, p. 53). But his interest in mathematics and the natural sciences had now been aroused. In 1799 he began to study natural sciences at Jena University, but had to abandon the course for financial reasons in the summer semester of 1801 and went on to assist his seriously ill father in his official duties until he died in February 1802.

Years of apprenticeship and travel

After the suffering of his childhood and youth, Fröbel now embarked upon his search for a profession which suited him. He was certainly not a ‘born educator’. He hit upon his true vocationby a round about route. In 1807, he commented on these early years:

I wanted to live in the open air, in the fields, meadows and woods […] I wanted to find in myself all those attributes which I saw in people who worked in the country (in the fields, meadows and woods): peasants, estate managers, hunters, foresters, surveyors […] That was my ideal of the countryman which took shape within me when I was about fifteen years old (Lange, 1862, p. 526 et seq.).

His understanding of nature acquired in his childhood and expressed in the first instance through an interest in the mathematical theory of surveying was deepened further by his fragmentary studies in Jena. In 1802, Fröbel became a surveyor (forestry office actuary) in the estates, forests and tithes office at Baunach near Bamberg and later in Bamberg itself. This was the time when he came across the writings of Schelling and read Von der Weltseele [On the soul of the world] (1798) and Bruno oder über das natürliche und göttliche Prinzip der Dinge [Bruno, or On the natural anddivine principle of things] (1802). He had by now acquired his first philosophical concepts o fnature. The writings of Novalis (Hardenberg) published in 1802 and Arndt’s Germanen und Europa [Germans and Europe] gave Fröbel his essential notions of idealistic subjectivity (Novalis) and of the historicity of the German nation (Arndt).

In 1803, Fröbel published an advertisement seeking employment in the newspaper Allgemeine Anzeiger der Deutschen. He decided in favour of a post as a private secretary on the Gross-Miltzow Estate near Neubrandenburg. He attached to his application a geometrical and architectural study (the plan of a small rural castle). He wanted to become an architect. After employment at Gross-Miltzow (1804–05), Fröbel moved to Frankfurt-am-Main where he took up a job in the building trade, but this experience was to prove a failure. In June 1805, however, Fröbel found employment in the local ‘model school’ in Frankfurt that was run on Pestalozzi’s principles of education. Fröbel felt that he had now found his true vocation. He wrote to his brother, Christoph:

I must tell you quite honestly that it is extraordinary how at home I feel in my employment […] It is as though I had been a teacher for a long time and was born for this profession; it seems to me that I have never wanted to live in any other circumstances than these (Lange, 1862, p. 533).

Contacts with the influential patrician family of the von Holzhausens in Frankfurt led Fröbel to travel to Yverdon in Switzerland in the autumn of 1806 to familiarize himself with Pestalozzi’s educational establishment. (The von Holzhausen family paid his travel costs.) Caroline von Holzhausen arranged to recruit Fröbel as the private tutor to her children. Between 1808 and 1810, Fröbel lived with his three young charges in Yverdon where he acquired further training in Pestalozzi’s elementary method and also endeavoured to give the von Holzhausen children the best possible training and education.

At this time, through his brother Christoph, who in his capacity as a pastor had some influence on the elementary school system in Fröbel’s home district, he attempted to introduce Pestalozzi’s concepts of elementary education into the Thuringian principality of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt, but this attempt failed. However, these endeavours played a very important part in Fröbel’s life and work. Here Fröbel wrote his first major publication: Kurze Darstellung Pestalozzis Grundsätze der Erziehung und des Unterrichtes (Nach Pestalozzi selbst) [A brief outline of Pestalozzi’s principles of education and training based on Pestalozzi himself] (Lange, 1862, p. 154–213). This comprehensive essay on Pestalozzi’s theory of elementary education shows just how influenced Fröbel was by Pestalozzi. At every phase of his later life and work, Fröbel’s pedagogics always remained within the orbit of Pestalozzi’s elementary education which he interpreted and developed further in his own independent manner.

Pestalozzi sought to bring about an improvement in the living conditions of the ‘lower classes’ of the population through the pedagogical stimulation of the ‘forces’ (elements) and ‘nature’ of each individual, especially the members of the most disadvantaged population groups. Man must acquire independence through his own ‘independent activity’ (Fichte). He must unfold all his forces of his own accord. This corresponds to the approach of the neo-humanist educational theory (Wilhelm von Humboldt). This development of the forces takes place ‘by categories’. The particular force must be tied to contents that are fully understood in such a way that basic concepts and categories of cognition and understanding of reality are built up in man. Thus, Pestalozzi’s elementary education, as the training of human forces (elements), also represents the development of categories because the (inner) force of man is developed in confrontation with the (outer) context. This development of categories is methodically stimulated and guided by education. Pestalozzi believed that education by categories—elementary education—could best be imparted by exerting a methodical influence on the child. He believed that three basic forces are present in every human being, that is, in every child: the force of ‘perception’ and ‘cognition’ (linguistic cognitive abilities); the force of ‘skills’ (control of the body, manual aptitudes); and ‘the moral or religious’ force (social and moral attitudes). These three basic forces constitute the ‘nature’ of man. They are the ‘elementary’ categories, yet cannot develop optimally on their own; they require stimulating support through education, tuition and the ‘method’. This stimulating support for the development of the forces present in the child itself must already begin in early childhood.

In 1805, in his Buch der Mütter [Book for mothers], Pestalozzi designed a programme of education by categories which cautiously suggested drawing on the mother’s love for the infant and pre-school child to impart an understanding of the structure of the child’s environment and so awaken and encourage the basic forces, the elements of human existence present in the child. Pestalozzi’s Book for mothers is the focal point of Fröbel’s 1809 publication on Pestalozzi and remained a decisive reference for Fröbel—until his own theory of educational games and his book of Songs of endearment for mothers of 1844, making direct reference to the earlier Book for mothers and setting out a programme of elementary education guided by scenes of the rural world during childhood.

When Fröbel came to Yverdon in 1808, Pestalozzi’s institute was at the height of its international fame. However, in 1809–10 tension between Niederer and Schmid (Pestalozzi’s principal colleagues) heightened and caused his institute to fade increasingly into the shadows of public attention. Pestalozzi involved Fröbel in this conflict. He escaped from this confrontation, in which he had taken the side of Schmid against Niederer and Pestalozzi, by leaving with the children under his care in the autumn of 1810. Fröbel continued to look after his three charges in Frankfurt am-Main until June 1811 when he moved to Göttingen in order to resume the study of natural sciences which he had been obliged to abandon in Jena.

Fröbel believed that the outcome of his years in Frankfurt and Yverdon had been unsatisfactory. He did not as yet possess his own independent philosophy of education. He was of the opinion that Pestalozzi’s theory of elementary education needed further development and a more solid foundation. What is more, he lacked sufficient specialized knowledge.

Fröbel now wished to embark on a broad course of study to acquire qualifications both as an educationalist and as a specialized subject teacher. He wanted his studies to take in ‘the philosophical disciplines, anthropology, physiology, ethics and theoretical pedagogics’ for use in teaching, as well as the ‘language knowledge (the mother tongue), history, geography and method’. He explained the reasons for this broad course of studies as follows: ‘There is admittedly an empirical approach to education which stems from a correct feeling and sense of things, as though born naturally, but in this case, too, learning will lead to a much deeper scientific culture’ (Lange, 1862, p. 536). Fröbel wrote to his brother, Christoph, from Göttingen that he was ‘engaged in the study of Asian languages, chemistry and physics, mathematics, might take up astronomy and some branches of medicine and was already following courses in the natural sciences and classical languages’ (Halfter, 1931, p. 312). This ‘general field of study’ with an encyclopedic tendency was, however, narrowed down at the expense of language studies, first in Göttingen and, above all, later on in Berlin, to the natural scientific subjects of chemistry, mineralogy, physics and geography.

However, Fröbel did not leave Frankfurt simply in order to pursue his professional training but also for personal reasons. His relationship with Caroline von Holzhausen, the mother of his charges and his own patron on many occasions, had become so intense that Fröbel preferred to escape from this tie. It is impossible to determine how close Caroline was to him. Perhaps she was more than just an intimate ‘soul-mate’ between September 1810 and June 1811. Fröbel repeatedly sent fragments of his educational philosophy to Caroline in the years that followed in letters carried by third parties; this suggests that they were very close. The fact that this relationship proved as hattering experience to Fröbel is confirmed by entries in his diaries for 1811 and 1816. In 1831, Fröbel still spoke of this relationship as:

the most dangerous fight that I have ever had to wage in my life […] A battle in which the heart and spirit, isolated from any intellectual attitudes, must be left to themselves […] Just as life is created out of death, so salvation comes from denial […] This struggle was sometimes truly terrible and ruinous to my life, leading me to the brink of moral destruction (Gumlich, 1936, p. 55,60).

Whatever may have been the motives for this conflict of June 1811, it proved the decisive reason which brought Fröbel to Göttingen where he set down his educational philosophy, the philosophy of the ‘sphere’ which is at one and the same time his scientific theory and his metaphysic. In Frankfurt, he had already become familiar with Fichte’s writings, but Schelling’s speculative philosophy of identity and objective idealism appealed even more to him. Strictly speaking, Fröbel’s philosophy of the sphere was therefore not a transcendental philosophy. Fröbel did not start out from reason as the source of categories and meanings as did Kant and Fichte; on the contrary, he viewed the human conscience, or man himself, as a part of the divine reality of creation. God is unity manifested in the contrasts of the world. Reality is always contradictory but strives towards unity. God, the creator, lies beyond this world but still remains a part of His creation (pantheism). Everything, every living being, is a creature of God and is determined by a divine force (His telos) which is represented in contrasts that in turn manifest an underlying unity:

The sphere (i.e. the constant, universally living and creating force which rests within itself) is the basic law of the universe, of the physical and mental (moral) world, of the moral and intellectual world, the sentient and thinking world (Gumlich, 1936, p. 62).

The spherical form is the representation of manifold variety in unity and of unity in variety; the sphere is the representation of the variety that develops out of unity and rests within it. It is the representation of the reference back from all variety to unity; the sphere is the representation of the origin and emergence of all variety from unity […] However, each thing develops only an imperfect spherical nature in that it seeks to represent its essence in itself and through itself in a single unit, in its unique individuality and variety and succeeds in that representation […] The purpose of man is primarily to develop his own spherical nature and then the nature of spherical being as such, to rain and represent that nature […] The spherical law is the basic law of all true and sufficient human education (Zimmermann, 1914, p. 150 et seq.).

While inanimate objects and other living beings simply live according to the spherical law manifested in them, man alone is consciously aware of that law. For him the spherical law means grasping his living potential in conceptual terms and acting according to this knowledge. When man understands his living potential through thought, he practises self-reflection and makes this potential conceptually accessible within himself through the process of thought. If he acts according to his insight into the spherical law, he gives expression to this relationship that is understood within him and so brings together the ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ factors of his life. But man must not merely reflect and act according to the insight acquired. He must also grasp external reality, that is, understand and internalize the ‘external’ and grasp this reality in its fundamental laws and structure: ‘Internalizing the external and externalizing the internal means seeking the unity of both in the general external form through which the purpose of man is manifested’ (Fröbel, 1826, p. 60). Fröbel understands education and teaching (tuition) as a stimulus and support for this dialectic process of the formation of categories: external reality must be understood in its internal laws and structure, but at the same time in such a way that this understanding is itself understood: the internal factor in man and the potential of his forces which must be unfolded and externalized. Thus, this process of the formation of categories embraces the areas of reality in their specific structure as relationships and at the same time the force of discovery present in man is made visible: nature in its mathematical structure refers to the anthropological premise of mathematical thinking. Both are mutually conditioning and one cannot exist without the other. For Fröbel, nature is ‘identity in contrast’ of the spirit (of human conscience) but the spirit can only be understood in nature or in externals by itself being externalized.

Fröbel’s philosophy of the sphere is therefore at one and the same time a scientific theory and a doctrine of education which lays the basis for the relationship between subjective cognition and the scientific object, while also providing the foundations for teaching which seeks to bring about education. Education is the analytical penetration of external reality in order to grasp its structures and understand the ability of the human mind to create these structures. This education by categories, which is at the same time elementary education in Pestalozzi’s sense, is Fröbel’s aim both in school education and in educational games for small children. For Fröbel, education and games do not involve either the projective self-presentation of the individual nor yet the random concern with alien contents, objects and themes. He is always interested in integration and mutual discovery of the self and objects, of the child and playthings, the pupil and the subject matter of teaching, in order to gain an insight into the reciprocal foundation—that is to say without an object there can be no subject and without man no (structured) external world.

However, in Göttingen Fröbel only set down the first drafts of his philosophy of the sphere (see Hoffmann & Wächter, 1986, p. 309–81). He did not write his planned summary treatise on the sphere. Further central statements on his philosophy of the sphere can be found in the six Keilhau publicity pamphlets which were published in 1820–23 and, in particular, in the second such document of 1821, entitled All-round education which fully satisfies the needs of the German character is the basic requirement of the German people (Zimmermann, 1914, p. 147–75).

Nevertheless, it is Fröbel’s main work, Die Menschenerziehung, referred to above, which deals in detail with the central concepts of the internal and the external and with his philosophy of the sphere. The notion of the sphere also reflects Fröbel’s endeavour to master his turmoil over Caroline von Holzhausen and his interest in crystallography. Fröbel sees the scientific law that explains the genesis of individual crystalline forms from one basic form as the natural scientific evidence, the concrete natural scientific reflection of his idea of the sphere, his educational theory, concept and philosophy of life.

In the 1830s, Fröbel ceased to speak, as he had done between 1811 and 1823, of the ‘law of the sphere’ or the ‘law of the internal and external’ and of their integration, and referred instead to the law of the ‘unification of life’. In his later work on educational games, the ‘intermediary law’ replaces the sphere. However, despite the use of different concepts, Fröbel always refers to the same process of idealistic access to the world by the individual through self-recognition of the human forces which create the world and, at the same time, remain bound by religious and metaphysical roots in the Christian idea of creation.

Fröbel’s years of travel included a move to Berlin in November 1812 to follow lectures on crystallography given by Professor Christian Samuel Weiss (1780–1856), the founder of crystallography. In Berlin Fröbel also attended lectures by Fichte. The war against Napoleon began in March 1813. Fröbel volunteered to serve in the Lützow rifles and took part in the war until May 1814. During the war he met two students of theology who had attended lectures by Schleiermacher and were later to become his colleagues: Wilhelm Middendorff (1793–1853) and Heinrich Langethal (1792–1879). Fröbel fought in the battles of Gross-Görschen and Lützen in May 1813. In June 1814, he resigned from his voluntary military service and took over an assistantship in August of the same year at the Mineralogical Institute of Berlin University under Professor Weiss. In December 1813 Fröbel’s brother Christoph, with whom he had been very close, died of cholera. Fröbel felt an obligation to his late brother and left his university position in April 1816 to take over the education of his three nephews, first in their parental home in Griesheim and then, after 1817, in Keilhau. He named his private school the General German Educational Establishment.

Keilhau: a model of spherical education

Fröbel’s first Keilhau pamphlet entitled ‘To our German people’ (1820) begins with these words:

From an unknown place, from a remote little valley of our common fatherland, a small band of men who are members of just a few families, all of them German, are speaking to you. They are bound by many ties: they are fathers, mothers, parents; they are brothers, sisters, relatives and friends […] They are united by love, love of their fellow men, love of education and representation of all that is human, of humanity in man (Zimmermann, 1914,p. 123).

Keilhau therefore centred on the educating family. Here teaching took place in a family atmosphere, raising and educating old and young pupils alike. The atmosphere of trust and ‘intimacy’ determined both aspects, (i.e. the family and the school) in which the growing human being develops and lives.

The Keilhau practice of raising and educating children addresses itself to the whole being on a scientific basis. It is all-embracing because it combines cognitive intellectual aspects with the physical and the manual, the social and the religious, that is, in Pestalozzi’s sense it integrates the elementary forces of the head and the heart to provide all-round education. In Keilhau, teaching did not take the straightforward form of the pupils receiving instruction from the teacher (the pupils themselves might become ‘teaching’ monitors). On the contrary, education was intended to mould the individual; it was moral and religious because the pupil was always emotionally integrated into the group, into the circle of his fellow pupils and into the ‘whole family’. What is more, education does not stop at training and the creation of insight in the pupil but also covers the physical side of the human being; that is, learning areas, which have features resembling training for work, are part of the programme. They include periods of educational games, sports and building work.Relationships understood in cognitive and rational terms are represented in the text by a drawing, asa model. Moreover, pupils were also able to work on the Keilhau farm. The Keilhau private schoolwas not only a boarding establishment but also included a small farm whose produce covered the most urgent material needs of the large Keilhau family.

However, the practice of educational tuition in Keilhau was not only comprehensive, covering all the facets and forces of the individual pupils. It was also scientific, purporting to reflect the spherical condition of unity between ‘nature’ and ‘spirit’, ‘science’ and ‘education’. Fröbel tried to establish a single root for education and science. The emotional framework of the family already serves as a way of penetrating and understanding the structure of reality. However, the family only supplies this transparency indirectly and in a situational manner. School education as ‘conscious’ education therefore goes beyond education provided within the family because the functionality of family life is taken further and deepened, rationally and continuously, by teaching and analysis of the structure of things. Thus Fröbel is able to define his educational practice as a ‘conscious’ family life.

Man is only educated if he practises science. Science and education are mutually conditioning and are transmitted through tuition. But man practises science when he is aware of the fact that the human conscience is the point at which man and external reality meet and are understood. Man practises science when he penetrates his own living world and the practice of his everyday existence, the wealth of phenomena in the living world, to arrive at their underlying structures and laws. Clearly the structure of a thing, its law, its characteristics and its spirit or inner being, as Fröbel calls it, are something which can only be understood through the humanconscience (the existence of the mind). By recognizing the characteristics of an object, one also comes to understand that man is the being, the only being, capable of knowing those characteristics. Science, as knowledge of the structure of (external) things, is also science that defines man’s ability to know. To that extent science and education fuse in Fröbel’s thinking. The educated man is a scientist and science brings forth education. The caring tuition given at Keilhau was therefore, in Fröbel’s view, the medium for combining elementary education and science. This can be done if tuition is caring, covering all the aspects (forces) of man and, at the same time, appealing to the pupil’s self-awareness. Keilhau education is thus the model of spherical education, because the pupil is taught here in the final analysis by things; the pupil recognizes the characteristics (the law and spirit) of things and so understands himself as a structuring spiritual being (see Heiland, 1993).

Fröbel’s main work, Die Menschenerziehung, which was written in Keilhau between 1823 and 1825, is therefore not just his educational philosophy and developmental theory, but also his school pedagogy, his theory of ‘caring tuition’. In Die Menschenerziehung and in his six short Keilhau pamphlets, Fröbel characterizes the relationship between education and science as the acquisition by man of self-awareness, as a relationship between the external and internal, a dialectic imbrication of the internal and external and their necessary ‘unification in life’. In his main work, however, Fröbel also describes a wealth of individual ‘foundation courses’ which are designed to train the elementary forces in man, and he emphasizes their basic principle: caring tuition is governed by the law of objects. Pupils must understand the object that is central to the lesson. Teaching helps the pupils to understand the structure of the object by encouraging them to pay attention to particular features and going on to give further indications. Thus, pupils become aware of themselves at the same time as learning to understand the object. Language teaching, for example, is not concerned with language in its external relationships, but with the education of man to become himself. Pupils discover their own principles and laws through language and also see themselves as being created by language. For Fröbel language is therefore always a medium, a way of putting across the ‘external’, as the designation of reality, and the ‘internal’, as intellectual productivity and creative linguistic potential. Similarly, Fröbel does not see mathematics as an accumulation of individual problems and operations, but as a principle which can only be grasped through a realization of the fact that man is the only being able to penetrate and structure reality on a mathematical basis, and break it down into relationships which can then be interpreted.

The caring tuition given in Keilhau is therefore, above all, cognitive, based on analysis, even though the mental/emotional and manual/practical sides are not overlooked. Fröbel is not concerned simply with teaching for work or with providing pupil-oriented vocational training, but rather with the acquisition of an insight into structures that remain firmly rooted in emotional and representational functions.

Keilhau family life, which was carried over into the manner of teaching, lay emphasis on the close relationship between life and cognition, between practice and theory. Keilhau thus also has certain unmistakable features of a rural educational home.

Fröbel’s marriage to Henriette Wilhelmine Hoffmeister in 1818, the daughter of a member of the Berlin War Council, the collaboration of Middendorff and Langethal, the move of Fröbel’s brother Christian with his family to Keilhau and the marriages of Middendorff and Langethal, as well as the good reputation of Keilhau, all enabled the school to succeed while Fröbel was, at the same time, incurring heavy debts. In November 1825, fifty-seven pupils were present in Keilhau and the establishment was flourishing. But, at the same time, it began to decline.

In 1829 only five pupils were left and the establishment was on the verge of collapse. This adverse situation was bound up with Metternich’s policy after 1815. National and democratic trends in Germany were impeded by conservative counter-currents (the Holy alliance, the Karlsbad decisions, the Prohibition of the brotherhoods and the ‘Persecution of demagogues’ after 1819). Keilhau did not escape these developments since it had the reputation of being a liberal and national institution, and was closely scrutinized by the Prussian police.

Fröbel himself was cross-examined in Rudolstadt. Although the investigating report came out in favour of Keilhau, a rumour spread among the general public that Keilhau was a ‘nest of demagogues’. Parents removed their children from the boarding school.

Fröbel tried to set up a ‘People’s educational establishment’ at Helba in the nearby Duchyof Sachsen-Meiningen, to which an establishment for the care of 3- to 7-year-old orphans was to beat tached. In an outburst of enthusiastic planning, he conceived a comprehensive system of schools: the Care Establishment (the forerunner of the kindergarten) and the next stage, the People’s educational establishment (equivalent to the primary school) with aims which were clearly oriented towards tuition through work and an understanding of the living world. These were to be followed at a subsequent stage by both the scholarly General German educational establishment at Keilhau (a grammar school) and a kind of vocational secondary school (an ‘Educational establishment for German art and German trades’ or a ‘Polytechnic school’). However, nothing was to come of this concept of a kind of cumulative comprehensive school.

Keilhau was barely saved from closure through the intervention of Johannes Barop (1802–78) who took over as head master in 1829.

In terms of writing, the Keilhau period between 1817 and 1831 was Fröbel’s most productive phase during which he wrote his six Keilhau publicity pamphlets: To our German people (1820); Comprehensive education satisfying fully the needs of the German character is the fundamental need of the German people (1821); Principles, purpose and inner life of the General German educational establishment at Keilhau near Rudolstadt (1821); On the General German educational establishment at Keilhau (1822); On German education as such and on the general German educational establishment at Keilhau in particular (1822); and More news of the general German educational establishment at Keilhau (1823). These short publications analyze the roots of Keilhau in the philosophy of the sphere, while also describing the individual courses, and so combining educational philosophy and school pedagogics or syllabus theory.

In some of these pamphlets, notably the first and fourth, Fröbel examines in detail his programme for a national education system, for which he took over the essential ideas from Fichte but without using nationalistic arguments. In his Die Menschenerziehung Fröbel paid no attention to this national programme but described the educational practice of Keilhau essentially in the framework of the philosophy of the sphere. This also holds good for his weekly ‘Educating Families’, the essays which describe both family life in Keilhau and certain courses (elementary geography and the theory of space).

The decline of Keilhau and the inability to get the Helba project off the ground were experienced by Fröbel as a failure. He decided to exercise his teaching activities elsewhere. Through contacts with the von Holzhausen family—he visited Frankfurt-am-Main in May 1831—he met the Swiss, Xaver Schnyder von Wartensee, who invited him to open a private educational establishment in Switzerland.

The Swiss years

The Wartensee Educational Establishment was opened in August 1831. It was never viable as a boarding establishment and remained a day school. In 1833, it was transferred to Willisau. The protestant Fröbel was attacked in public by clerical (Catholic) circles and also by pupils of Pestalozzi (Niederer and Fellenberg). To bring his own pedagogics to the attention of public opinion, he published in 1833 his Principles of the education of man, which had actually been written in 1830 (Lange, 1862, p. 428–56).

The canton of Bern was planning to set up an orphanage for the poor. Fröbel presented four separate plans (Geppert, 1976, p. 235–76). These plans, like the syllabuses for Wartensee and Willisau, revealed the lingering influence of the Helba People’s Education Establishment concept.

Despite the continuing validity of the principle of training all the different forces in the human being, ‘creative action’ now came to the fore. Teaching in the morning was to be followed by practical farm and handicraft work in the afternoon. However, this educational establishment for the poor did not see the light of day.

As Fröbel had patrons in the Bern cantonal council, in April 1834 he was entrusted with the task of training four future teachers (‘schoolteacher apprentices’) and with heading an advanced training course for elementary school-teachers. Fröbel conducted his advanced training course again in 1835. Detailed documentation on these activities is lacking. However, the available material does clearly show Fröbel’s approach to teacher training: it should consist of three aspects—general education, basic familiarization with teaching methods and pedagogics.

In 1834, Fröbel learned that the Bern cantonal government was planning to put him in charge of the existing orphanage (with an elementary school) at Burgdorf. In that capacity, Fröbel believed that he could now put into practice the central part of his Helba project—the ‘People’ seducational establishment’ as it was now called. In a letter to the Bern Councillor Stähli in March 1834, Fröbel set out the plan for an establishment of that kind, together with the Burgdorf orphanage, the educational establishment for the poor, a teacher training institute and a people’s university—that is, a whole system of educational establishments centring once again on the ‘People’s educational establishment’ with its emphasis on ‘creative action’ combining theoretical teaching with life, and tuition with practical work.

However, this concept was not put into place either. But Fröbel did become headmaster of the Burgdorf orphanage and its attached elementary school in mid-1835. The elementary school was not opened until May 1836 when Fröbel returned to Germany with his sick wife.

The educational plans for the Burgdorf elementary school date from 1837 and 1838, i.e. they were drafted by Langethal who headed the school (and the orphanage) after Fröbel had left. These plans offer courses for three classes, 4- to 6-year-olds, 6- to 8-year-olds and 8- to 10-year olds.While the courses for second and third classes coincide largely with the ideas set out in Die Menschenerziehung, the syllabus for the first class as the foundation for all subsequent subject teaching now focuses on games. A bridge was thus thrown to the next phase in Fröbel’s life which centered on the education of infants through games (see Lange, 1862, p. 479–507, 508–20).

The final years

At the end of 1835, Fröbel wrote a publication entitled The Year 1836 Demands the Renewal of Life, which begins with these words:

It is the announcement and proclamation of a new spring of life and mankind which rings so loudly in my ears in and through all the manifestations of my own life and the lives of others. It is you, the renewal and rejuvenation of all life, who speak out, through everything and in everything within and around me, so actively and clearly to my spirit. This time has been so long awaited by mankind and for so long promised to it as its golden age (Lange, 1863, p. 499)

The ‘golden age’ sees the family become ‘sacred’ again in the shape of the ‘holy’ family. The family heals the relations between parents and children and between siblings through an improved atmosphere, through shared play.

Fröbel now departed from his original plan of using school tuition, set out in Die Menschenerziehung, following the failure of the Helba project, the decline of Keilhau and the limited successes achieved in Switzerland. He now set his sights on the family and built up an associative organization that was not yet subject to any form of State control. He developed play materials to improve the pedagogical atmosphere in (bourgeois) families and wished to help found associations of parents who might exercise a stimulus on others through their experiences of play.

The creation of the kindergarten was not the first step in this last phase of Fröbel’s life, but in effect became an outcome that he had not been seeking at all. Fröbel wished to change the family so as to make it the focal point of the education of man. He wanted to facilitate ‘spherical’ education from early childhood onwards, heralding the new ‘spring of mankind’. This spherical education of infants and pre-school children is effected using the play material developed by Fröbel. This programme was later to become the kindergarten—professional educators (‘kindergarten nurses’) looked after small children at play. Fröbel’s play teaching, which was originally to take place within the family, was now transferred elsewhere so that one important feature of his original idea of education through play was lost.

When Fröbel came back to Germany in 1836 he already had some play material, which he called ‘gifts’, in his luggage. In 1836, he opened an ‘Establishment to Take Care of the Activity Needs of Children and Young People’ at Bad Blankenburg in Thuringia, in effect a kind of toy factory.

He produced the first ‘gift’: six little woolen balls made from threads in the colours of the spectrum; and the second one: wooden spheres and cubes together with a cylinder; and finally the third one which consisted of a cube subdivided into eight further small cubes. Fröbel also made ‘cut out books’ and materials for school tuition, e.g. a ‘self-learning language cube’ or spatial (mathematical) cube. A ‘self-teaching’ or ‘speaking’ cube meant that the surfaces of the cube carried transfers containing information on the cube as a mathematical shape. This information also pointed to different forms of speech.

Fröbel did not develop this material any further because it was, in practice, only used to a limited extent in schools. However, these materials were important to his theory of play, since they demonstrated the relationship between school and kindergarten education: the information imparted to the pupil by the message on the surfaces of the ‘self-teaching’ cube would now be provided for the pre-school child through play using the ‘gifts’ and ‘occupations’, i.e. through active participation, construction and building, thereby bringing to light their structure, laws and nature as objects in relation to the child-subject.

The ‘self-teaching’ aspect is therefore still clearly present in Fröbel’s new play materials. Through play, the ‘gift’ imparts to the child its properties and structure. With his ‘gifts’ and ‘occupations’ for pre-school children, Fröbel went beyond teaching materials as such and completed the auto-didactic aspect using games involving the participation of adults in the play of children, who could assist the child with suggestions and explanations while it is engaged in building and playing. Fröbel’s educational games are therefore also a model of spherical education and intended to shape the child, no longer through ‘science’ but rather through active contact with elementary forms which clarify and symbolize the ‘general’ features of the objects concerned.

In March 1838, Fröbel combined his ‘Establishment to Take Care of the Activity Needs of Children and Young People’, which was originally to be called the ‘Auto-Didactic Establishment’, with an ‘Establishment to Train Child Leaders’.

Fröbel’s wife, Henriette Wilhelmine, died in May 1839. On 28 June 1840, the ‘General German Kindergarten’ was opened in the town hall at Blankenburg within the framework of the Gutenberg memorial celebrations.

After 1844, Fröbel was living in Keilhau again, but in 1848 he moved to Bad Liebenstein where he opened the ‘Establishment for the Universal Unification of Life through the Developmental and Caring Education of Man’. This was a kindergarten together with a boarding establishment to train future kindergarten nurses. In May 1850, Fröbel moved to the Marienthal hunting lodge near Schweina where he married his second wife, Luise Levin, in June 1851 and where he died on 21 June 1852.

Fröbel welcomed the March Revolution of 1848 and hoped that it would bring not only revolutionary political innovations but also promote the spread of his kindergartens. With that end in view, he invited visitors to attend an assembly of teachers at Rudolstadt in August 1848. Here the pedagogical relationship between the kindergarten and elementary schools, and the important role of Fröbel’s play materials in the school system were discussed. This conference of elementary school-teachers tabled a motion to the Frankfurt National Assembly calling for the introduction of Fröbel’s kindergartens as an integral part of the standard German education system. The failure of the revolution also marked the end of Fröbel’s influence on the reshaping of pre-school establishments, ‘schools for small children’ and ‘day-care establishments’ into kindergartens or pedagogical institutions.

Fröbel’s contacts with free-thinking circles and the undogmatic and unorthodox attention to religion practised in his kindergartens led the Prussian government to ban these establishments throughout its territory in August 1851.

Fröbel popularized his play theory in many different ways, but did not summarize it in one particular text. The first documents on play and the ‘gifts’ were written in 1837 and published in the Sonntagsblatt in 1838 and 1840. This was Fröbel’s second weekly after his Educating families of 1826. In 1838, two small publications on the first and second ‘gifts’ appeared. In 1843, Fröbel published News and accounts of the German kindergarten and in 1844 his educational ideas for infants, known as the Songs of endearment for mothers, as well as his pamphlet The new third gift. In 1848, Middendorf wrote his ‘Kindergartens: A Need of Our Age—The Foundation of Unifying Education of the People for the Frankfurt Parliament with the co-operation of Fröbel. In1850, Fröbel’s third weekly appeared: Friedrich Fröbel’s Weekly: a Unifying Journal for All Friends of Education. In 1851 and 1852, he published his last weekly under the title Periodical for Friedrich Fröbel’s Endeavours to Implement Developmental and Caring Education in the Context of the Universal Unification of Life.

In 1851, Fröbel published a pamphlet containing an extended version of his essay on the third ‘gift’ taken from the Sonntagsblatt (1838)—this was his last major independent publication.

Fröbel’s international stature is founded on the fact that his kindergarten was a teaching centre for 3- to 6-year-old children which stood in complete contrast to the pre-school establishments of his own day; the latter were either mere child-minding centres or provided formal tuition. Fröbel, on the other hand, wanted to develop educational procedures founded on play. That is how he intended to allow for the child’s perception of things, while at the same time imparting elementary education.

Fröbel’s original intention of teaching young children through educational games in the family became linked after 1840 with the social demand for ongoing daily care of young children in an establishment outside the home. Fröbel’s concept of the kindergarten as a model play establishment for mothers who could see there how his ideas of educational games were practised now became an institution in which play was organized professionally. Fröbel’s mostly male specialists for popularizing the idea of play in the family now became female kindergarten nurses who were professional play organizers, and had been trained by Fröbel in courses lasting up to sixmonths.

In Fröbel’s day the kindergarten, including his own establishment at Bad Blankenburg, involved three activities. It centered on play with the ‘gifts’ and ‘occupations’. Alongside these, ‘movement games’ were played involving running, dancing, games played in the round and acting. The children’s play group developed forms of movement without game material. The third area was ‘garden care’. Here the kindergarten pupil was to learn about the development of plants, their growth and blossoming, and to see how careful tending can influence their development. Here they oung child could see a mirror image in nature of his/her own growth.

However, the kindergarten centred on materials: simple objects like a ball, a sphere, a cube and a rod. Fröbel structured this system of ‘toys’ into materials of different shapes with line and dot patterns; he describes their features by separation (analysis) showing the four basic types of materials, and by joining the pieces together again (synthesis). Here Fröbel starts out from the unity (of the ball) and returns through increasingly clearly structured and separable materials to his beads as dot-shaped materials, and so back to spherical structures. All this is intended to reveal the cosmos and creation through building, thus enabling the child to experience imagined and perceive delementary structures of reality through its own action. Fröbel gave particular attention to physical materials, especially in ‘gifts’ 3 to 6, known as the ‘building boxes’: the third gift contains eight part-cubes, the fourth eight squares, the fifth twenty-one part-cubes and the sixth eighteen squares. Building with these elementary pieces enables an almost inexhaustible variety of shapes to be obtained which Fröbel typified as ‘living shapes’ (shapes of the living world), ‘beautiful shapes’ and ‘cognitive shapes’ (mathematical groupings).

Fröbel’s last major work, his Songs of Endearment for Mothers, was published in 1844; this was a pedagogical scheme for infants and 1- to 2-year-old children who were still too young to attend his kindergarten. In his Songs of Endearment for Mothers, Fröbel comes very close to the everyday living world that he represents in scenes (pictorial illustrations), finger games and nursery rhymes. Experiences of the child’s everyday life are acted out through the perceived physical medium of finger games or in illustrations. The mother plays the finger game and the child is asked to imitate it. This book is a sequel to Pestalozzi’s Book for Mothers, but moves beyond that author’s cognitive and schematic method.

Fröbel’s principle is motherly love. The mother shows loving care for her child through play. Initially, the infant is a being at one with himself/herself. As its own forces then begin to develop, i.e. its motor system, senses and intelligence, the child begins to become familiar with its surroundings and is able to differentiate and structure them. The true self gradually becomes structured and differentiated through this experience of the outside world.

Influence

When Fröbel died in June 1852 his life’s work seemed to have been a failure. The ban on kindergartens in Prussia initially prevented any further spread of Fröbel’s educational games in Germany. The fact that his pedagogical scheme acquired worldwide significance is due in no small measure to Bertha von Marenholtz-Bülow (1810–93) who became friendly with Fröbel in the last years of his life—as did Diesterweg—and began to publicize Fröbel’s scheme of kindergarten pedagogics posthumously through lectures and exhibitions in other West European countries, e.g. in Belgium, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

Strong Fröbel movements grew up, in particular in the Netherlands and Switzerland, and took care of the subsequent spread of Fröbel’s kindergartens. In the United Kingdom, an independent national Fröbel movement was formed in the shape of the Fröbel Society which later became the National Fröbel Union and was led by Johann and Bertha Ronge, Adele von Portugall, Emilie Michaelis and Eleonore Heerwart; they published textbooks on Fröbel games and established training centres for kindergarten educators. In the United States, Elisabeth Peabody, Mathilde Kriege and Maria Kraus-Boelte publicized Fröbel’s ideas. In the 1880s and 1890s, the influence of the North American movement led to the introduction of kindergartens in Japan.

Marenholtz-Bülow’s most prominent pupil, Henriette Schrader-Breymann (1827–99), founded the Pestalozzi-Fröbel House in Berlin in 1873 and developed her own particular concept of kindergarten pedagogics which combined aspects of Pestalozzi’s and Fröbel’s theories. She was particularly active in encouraging the spread of kindergartens in Scandinavian countries. The German Fröbel movement had an unmistakable influence in the second half of the nineteenth century on the development of institutional pre-school education in Poland, Bulgaria, Bohemia, Hungary, Russia and also in Spain and Portugal, as has been demonstrated by historical research.

The international success of Fröbel’s educational programme for kindergartens can betraced back to the increasingly urgent need for pedagogical care of pre-school children as a result of the process of industrialization. Concepts such as child-minding or formal school-teaching did not correspond to the spirit of that age. Fröbel’s elementary ‘education of man’ through play with activities that appealed manifestly to all the forces of the child, seemed more appropriate to the needs of society. His kindergarten pedagogics combined the social aspect of care with elementary education through play, and thus paved the way for subsequent formal education without any excessive intellectual strain.

However, Fröbel’s kindergarten programme owes much to the educational theory of neo humanism:Fröbel is concerned with the education of the human being and not with the training and development of a ‘viable’ citizen.

This concept of kindergarten education, founded on the philosophy of the sphere, underwent far-reaching changes within the Fröbel movement in the second half of the nineteenth century. Marenholtz-Bülow helped to save Fröbel’s kindergartens from oblivion, but also interpreted them in polytechnic-functional and cultural-philosophical terms, thus adapting them to the spirit of the industrial age. As a result, the kindergarten in effect became part of the school system dependent on socio-economic reproduction and legitimation. Meanwhile, although Marenholtz-Bülow was perfectly familiar with the foundation of Fröbel’s pedagogics on the philosophy of the sphere, she did not take sufficient account of that fact.

The new concept of Fröbel’s play-care, developed by Schrader-Breymann in the 1880s and the Fröbel movement after the turn of the century, was oriented towards developmental psychology and educational reform, and completely overlooked the original foundations of the kindergarten. Fröbel’s gardening activities, his movement games and the play materials now became means to the end of developing relationships with the living world and everyday routine, for example through the didactic category of Schrader-Breymann’s ‘object of the month’ (cf. Heiland, 1982, and Heiland,1992).

In the twentieth century the kindergarten has admittedly remained an establishment to which the name of Fröbel is linked worldwide, but it has been exposed to many different influences. Since the collapse of the German Fröbel movement (about 1945), it has become an institution for infant pedagogics and pre-school education with pronounced group psychological and sociopedagogical objectives. As such, it has ceased to be determined by aspects of Fröbel’s original kindergarten pedagogics.

Nevertheless, Fröbel’s elementary education in the kindergarten involving games with authentic play materials and, in particular, with the ‘building boxes’ (‘gifts’ 3 to 6) remains an important contribution to pre-school education. The constructive handling of simple play materials permits concentration on objects and a varied experience of the properties of materials through building and shaping activities, which also favours social learning and thus satisfies Fröbel’s demand for the ‘unification’ of life (Heiland, 1989, p. 91 et seq., 128 et seq.).

Primary literature on Freidrich Fröbel

Fröbel, F. 1826. Die Menschenerziehung [On the education of man]. Keilhau; Leipzig, Wienbrack.

Geppert, L. 1976. Friedrich Fröbels Wirken für den Kanton Bern [Friedrich Fröbel’s activity for the Canton of Bern]. Bern; München, Francke.

Gumlich, B. 1936. Friedrich Fröbel: Brief an die Frauen in Keilhau [Friedrich Fröbel: letter to the women of Keilhau]. Weimar, Böhlhaus Nachfolger.

Heiland, H. 1972. Literatur und Trends in der Fröbelforschung [Literature and trends in research on Fröbel]. Weinheim, Beltz.

——. 1990. Bibliographie Friedrich Fröbel [Bibliography on Friedrich Fröbel]. Hildesheim, Olms.

Hoffmann, E.; Wächter, R. 1986. Friedrich Fröbel: Ausgewählte Schriften — Briefe und Dokumente über Keilhau [Friedrich Fröbel: selected writings — letters and documents from Keilhau]. Stuttgart, Klett-Cotta.

Lange, W. 1862. Friedrich Fröbels gesammelte pädagogische Schriften. Erste Abteilung: Friedrich Fröbel in seiner Erziehung als Mensch und Pädagoge. Bd. 1: Aus Fröbels Leben und erstem Streben. Autobiographie und kleinere Schriften [Friedrich Fröbel’s collected educational writings. first part: Friedrich Fröbel’s educationas a human being and teacher. Vol. 1: On Fröbel’s life and early endeavours. autobiography and short texts]. Berlin, Enslin.

——. 1863. Friedrich Fröbels gesammelte pädagogische Schriften. Erste Abteilung: Friedrich Fröbel in seiner Erziehung als Mensch und Pädagoge. Bd. 2: Ideen Friedrich Fröbels über die Menschenerziehung und Aufsätze verschiedenen Inhalts [Friedrich Fröbel’s collected educational writings. first part: Friedrich Fröbel’s education as a human being and teacher. Vol. 2: Friedrich Fröbel’s ideas on the education of men and essays on various subjects]. Berlin, Enslin.

——. 1866. Friedrich Fröbel: Mutter- und Koselieder [Songs for mothers and children]. Berlin, Enslin.

Zimmermann, H. 1914. Fröbels kleinere Schriften zur Pädagogik [Fröbel’s lesser writings on education]. Leipzig, Koehler.

Secondary literature on Friedrich Fröbel

Halfter, F. 1931. Friedrich Fröbel: Der Werdegang eines Menschheiterziehers [Friedrich Fröbel: the career of an educator of humanity]. Halle/S, Niemeyer.

Heiland, H. 1982. Fröbel und die Nachwelt: Studien zur Wirkungsgeschichte Friedrich Fröbels [Fröbel and his influence: studies on the impact of Friedrich Fröbel’s Work]. Bad Heilbrunn, Klinkhardt.

——. 1989. Die Pädagogik Friedrich Fröbels [Friedrich Fröbel’s education system]. Hildesheim, Olms.

——. 1992. Fröbelbewegung und Fröbelforschung [The Fröbel Movement and research on Fröbel]. Hildesheim, Olms.

——. 1993. Die Schulpädagogik Friedrich Fröbels [Friedrich Fröbel’s formal education system]. Hildesheim, Olms.

Kuntze, M.A. 1952. Friedrich Fröbel: Sein Weg und sein Werk [Friedrich Fröbel: his life and work]. 2.nd edtion. Heidelberg, Quelle & Meyer.

Copyright notice

This text was originally published in PROSPECTS: the quarterly review of comparative education (Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education), vol. XXIII,no. 3 / 4, 1993, p. 473–91.

Reproduced with permission. For a PDF version of the article, use:

http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/archive/publications/ThinkersPdf/frobele.PDF

Photo source: Wikimedia.