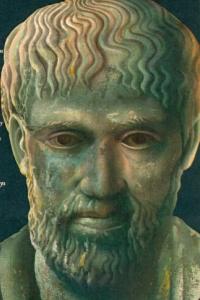

Aristotle (384-322 B.C.)

We are familiar with Aristotle the researcher, the founder of sciences, the logician and the philosopher, ‘the master of those who know’. But we know little of Aristotle the educator. Historians have not been greatly interested in what he has to say about education. The opinion expressed by H.I. Marrou in his Histoire de l’éducation dans l’Antiquité(History of Education in Antiquity) is indicative: ‘Aristotle’s work on education does not seem to me to be as original and creative as that of Plato or Isocrates.’

Yet Aristotle devoted as much time to teaching as to research. He is the prototype of the ‘professor’. His teachings and lectures are the part of his work that has been handed down to us over 2,300 years. A pedagogical concern and an educational dimension are present throughout his writings. It is high time a study was made of Aristotle’s approach to education as revealed in his lectures. This would highlight his characteristic manner of posing a problem and then discussing it by approaching it from different angles, probing it. We can discern here the didactic method of the Socratic and Platonic dialogues. Unfortunately the dialogues that Aristotle wrote to popularize the fruits of his research have all been lost. Such a study would also point out the way in which he illustrated his lectures with examples, quotations, references and images. On several occasions he declared that ‘it is impossible to think without images’.2

Aristotle was an academic throughout his career. At the age of 18 he entered one of the most renowned centres of learning of his day, Plato’s Academy, where he became noted for the passion with which he devoted himself to his studies, particularly to reading, a trait which won him the nickname of ‘reader’. He then built up the first great library which served as a model for the libraries of Alexandria and Pergamon.3He became a privat docent in rhetoric and a rebellious one too, openly and passionately criticizing the doctrines of Plato, his master and forerunner, who reportedly said of him: ‘Aristotle has kicked me just as a colt kicks it mother.’4 After Plato’s death, Aristotle left Athens for Assos in Asia Minor and three years later settled at Mytilini on the island of Lesbos. There he engaged in many types of research, particularly in biology. It is not known for certain whether he established schools or study circles at that period of his life but it is quite probable. In 342, at the age of 41, he was invited by Philip of Macedon to his court to become the tutor of the young Alexander.

Unfortunately, we know practically nothing about the relations between Aristotle the educator and his pupil Alexander. Yet what an extraordinary event it was! Jacob Burckhardt considered that it was through the education of Alexander that Aristotle exerted his greatest influence on history.5 Peter Bamm has described the encounter in the following words:

Aristotle, that man who with his thoughts constructed a dwelling so vast that it accommodated Western science for 2,000 years, helped, through the ideas he inculcated in Alexander, to create the conditions necessary in order that the West itself might come into being. If it had not been for Alexander we should hardly know the name Aristotle.

Without Aristotle, Alexander would never have become the Alexander we admire.6 Again, we know practically nothing for certain about the education that Alexander received from Aristotle. It seems likely that Aristotle prepared for his pupil an annotated version of the Iliad which was to accompany the conqueror to the limits of the known world. Aristotle may conceivably have written for Alexander one book on monarchy and another on the colonies. None of these works has survived to our times and, surprisingly, there is no mention of Alexander in any of the works that have been preserved except, perhaps, for several very vague allusions when Aristotle speaks of the king who is a perfect man. It is quite likely that Aristotle introduced the young Alexander to the natural sciences. And it could well have been Aristotle who aroused in Alexander that sense of curiosity, that passion for discovery and new experience which took him as far as India and would most probably have led him to explore Africa had he not died prematurely. Was it the education he received from Aristotle that made Alexander as much an explorer as he was a conqueror?

In 334 Aristotle returned to Athens and established his own school, the Lyceum.7 This was a type of university where research was pursued as an extension of higher education. Courses for the enrolled students were held in the morning, while the school was probably open in the afternoon to a wider public and thus performed the function of an open university. It seems that Aristotle entrusted the running of the Lyceum to the various members of the teaching staff in turn, each assuming this responsibility for ten days at a time.8 Can this be said to foreshadow the democratization of education?

Scientific research, philosophical reflection and educational activity were intimately linked in Aristotle’s life and work. It is therefore not surprising that Aristotle, whose passion for methodical analysis extended to whatever attracted his inquiring mind, also analysed the problems posed by education. He refers to the subject in practically all his writings.

Unfortunately, the works in which he systematically developed his ideas on education have survived in only fragmentary form. Of his book On Education there remains only the merest fragment. The exposition of his education system to be found in the Politics terminates abruptly: a good half of it must have been lost. Using these few pieces of mosaic we shall try to sketch an outline of Aristotle’s paideia.

The goal or purpose of education

For Aristotle the goal of education is identical with the goal of man. Obviously all forms of education are explicitly or implicitly directed towards a human ideal. But Aristotle considers that education is essential for the complete self-realization of man. The supreme good to which all aspire is happiness. But for Aristotle the happy man is neither a noble savage, nor man in his natural state, but the educated man. The happy man, the good man, is a virtuous man, but virtue is acquired precisely through education. Ethics and education merge one into the other. Aristotle’s ethical works are teaching manuals on the art of living.

In the first book of The Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle asks in an unequivocal manner ‘whether happiness is to be acquired by learning or by habituation or some other sort of training, or comes in virtue of some divine providence or again by chance’.9 The reply is equally clear: ‘virtuous activities […] are what constitute happiness’.10 There are two categories of virtue: intellectual and moral.11 ‘Intellectual virtue in the main owes both its birth and its growth to teaching (for which reason it requires experience and time) while moral virtue comes about as a result of habit.[…] None of the moral virtues arises in us by nature.’12 We shall return to the distinction made here between ‘teaching’ and ‘the result of habit’ when we come to discuss Aristotle’s pedagogy. He concludes: ‘It makes no small difference, then, whether we form habits of one kind or of another from our very youth; it makes a very great difference, or rather all the difference.’13 The point could not be more tersely made. Towards the end of The Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle returns to the question in almost identical terms: ‘The man who is to be good must be well trained and habituated.’14 In Book VII of the Politics, where Aristotle discusses the ideal state and, in particular, education in that state, he returns to the question, ‘How does a man become virtuous?’ The reply15 is similar to the one given inThe Nichomachean Ethics. Three things make men good and virtuous: nature, habit and rationality. Everyone must be born a man as distinct from the brute beasts; and he must have certain qualities both of body and soul. But there are some qualities with which it is useless to be born, because habit alters them: nature implants them in a form which is susceptible of change, under the impulse of habit, towards good or bad. Brute beasts live mostly under the guidance of nature, though some are to a small extent influenced by habit as well. Man alone lives by reason, for he alone possesses rationality. In his case, therefore, nature, habit and the rational principle must be brought into harmony with one another; for man is often led by reason to act contrary to habit and nature, if reason persuades him that he ought to do so. We have already determined what natures will be most pliable in the legislator’s hand. All else is the work of education; some things are learned by habit and others by instruction.

Hence certain attributes are necessary in order to achieve happiness, the full development of the human being. One must be fortunate enough to possess from birth certain natural gifts, both physical and moral (a healthy and beautiful body, a certain facility, intelligence and a natural disposition towards virtue). But these are insufficient. It is only through education that potential happiness can become truly accessible. Education is the touchstone of Aristotelian ethics. The virtues, wisdom and happiness are acquired through education. The art of living is something to be learned.

Aristotle’s ethics are based on such concepts as happiness, the mean, leisure and wisdom, which we also encounter in his theory of education.

Clearly in Aristotle’s view all forms of education should aim at the mean.16 The eighth and final book of thePolitics (following the traditional order of the text) ends abruptly with a reference to this principle. ‘Clearly, then, there are three standards to which musical education should conform. They are the mean, the possible, and the proper.’17 The concept of the mean does not only apply to the ends of education, it is also an instrumentality, a pedagogical imperative to which we shall return later.

The goal of human action is leisure;18 moreover, ‘happiness is thought to depend on leisure’.19 And one of the essential goals of education that should always be borne in mind is precisely leisure20 or schole (which is the etymological root of the word ‘school’). In the Aristotelian philosophy of education a central position is occupied by education for leisure. This is an essential part of the training for the ‘business of being a man’. Tricot rightly emphasizes that leisure is not to be confused with idling,21 with a kind of dolce farniente. It is the faculty of being able and knowing how to use one’s time freely. Freedom is one of the ultimate goals of education, for happiness is impossible without freedom. Such freedom is achieved through contemplation or the philosophical life, that is to say, in the activity of the mind relieved of all material constraints. This is why it is particularly important that education should not have the character of vocational training. For ‘the meaner sort of artisan is a slave, not for all purposes but for a definite servile task’.22 Furthermore, ‘the good man, therefore, the statesman, and the good citizen certainly should not learn the crafts of their inferiors, except occasionally and for their own advantage’.23 The same remarks also apply to tradesmen. Aristotle illustrates this point of view in his extremely detailed account of musical education in Book VIII of the Politics. He says, for example, that ‘neither the flute nor any other instrument requiring abnormal skill […] should be made part of the curriculum’.24 And he ends with the categorical statement that: accordingly, we reject the professional instruments; and we reject also the professional mode of education (by ‘professional’ I mean such as is employed in musical contests) in which the performer practises his art not for the sake of improving himself, but in order to provide his audience with entertainment-and vulgar entertainment at that.

For this reason we consider that the performance of such music is beneath the dignity of a freeman; it belongs rather to hired instrumentalists, who are degraded thereby.25

Leisure, or schole, which should be the goal of education, is the freedom to apply oneself to essential matters. It is this form of freedom that leads to wisdom: a life devoted to philosophy and contemplation, that is true happiness. Through leisure, which is an indication of freedom, education should lead to man’s ultimate goal, an intellectual life rooted in the mind. That is the true ‘business of man’ which it is the function of education to teach. And man can only learn it through education.

But man is essentially a political animal, according to Aristotle’s celebrated definition. ‘A man who cannot live in society, or who has no need to do so because he is self-sufficient, either a beast or a god; he is no part of a state.’26 Man can only achieve fulfilment in the community of the polis. Only there can he find happiness. (It should always be borne in mind that in his treatment of politics Aristotle is thinking exclusively of the polis, the city-state with precisely defined limits.)

If our thesis is correct and all Aristotle’s practical philosophy rests on his theory of education, then we should find a genuinely political dimension as well as an ethical dimension in his concept of the goal of education. This is indeed the case. Just as education leads the individual to virtue, which is the essential source of happiness, so also it creates the conditions necessary for the establishment and stability of the virtuous polis, that is to say, the polis that ensures the happiness of its citizens. It is through education that a community is formed. ‘The state […] is a plurality; it should be formed into a social unit by means of education.’27

At the beginning of his Politics, Aristotle declares that ‘the state is a creation of nature’.28 But when he describes the ideal state, he emphasizes that ‘a good state, however, is not the work of fortune, but of knowledge and purpose’.29 And this is the sentence with which he introduces his discussion of education in Books VII and VIII of Politics. But education does not only create society, the community which constitutes the city, it also guarantees its stability:

The most powerful factor of all those I have mentioned as contributing to the stability of constitutions, but one which is nowadays universally neglected, is the education of citizens in the spirit of the constitution under which they live.

You may have an unsurpassed legal system, ratified by the whole civic body; but it is of no avail unless the citizens have been trained by force of habit and teaching in the spirit of the constitution.30

Thus education has a conservative role, as Aristotle rightly recognizes. Today’s advocates of social progress tend to criticize education for resisting change. But in Aristotle’s view change is not desirable in itself as any change may lead to ‘corruption’. What he seeks is an achievable and stable ideal. For each society and each form of government there exists a system of education. There is a system of education that corresponds to democracy, another which is appropriate for an oligarchy.31 It is for that reason that education is the primordial task of the legislator: No one can doubt that it is the legislator’s very special duty to regulate the education of youth, otherwise the constitution of the state will suffer harm. The citizen should be trained in accordance with the particular form of government under which he is to live; for each type of constitution has a distinctive character which originally formed it and makes possible its continued existence…again some preliminary training and habituation are required for the exercise of any faculty or art; and the same, therefore, obviously applies to the practice of virtue.32

There is one final feature which I wish to include in this sketch of the Aristotelian concept of the goal of education. If leisure is to be the goal of education for the individual, education at state level must be an education for peace. Just as leisure is the goal of occupation, so peace is the goal of war.33 Again, life as a whole is capable of divisions: activity and leisure, war and peace. […] War must be looked upon simply as a means to peace, action as a means to leisure, acts merely necessary or useful as a means to those which are good in themselves. The statesman should bear all this in mind when he drafts his laws. […] It is with these ends in view that children, and indeed adolescents at every stage of education, should be trained.34

The education system

In view of the essential role which education is required to play in the development of the individual and of society, Aristotle devotes a great deal of space to the development of an education system in his description of the ideal city. Unfortunately, only a fragment of this description has survived. A good many questions therefore remain unanswered.

Aristotle believed that, contrary to the common practice of his day, education was a responsibility of the state. What he works out is therefore a genuine education policy. Like Plato, Aristotle devises a veritable system of continuing education. Education is not limited to youth; it is a comprehensive process concerning the whole human person and lasting a lifetime. This process is organized in periods of seven years (just as in Plato’s system). The first period is that of pre-school education. This is the responsibility of parents and more particularly of the father, who is ‘responsible for the existence of his children, which is thought the greatest good, and for their nurture and upbringing’.35 Upbringing begins well before birth: `the legislator must decide how best to mould the infant body to his will’.36 With this end in view, Aristotle indicates the best age for father and mother and even the best period for conception, namely winter. During pregnancy ‘pregnant women also must take care of their bodies’,37 they should‘ take exercise and eat nourishing food [and] keep their minds as tranquil as possible’. The newborn should have ‘food with the highest milk content’ and ‘the less wine the better’. Children must exercise their bodies and become accustomed to the cold from their earliest years. Up to the age of 5 they should be trained through games, ‘but they must not be vulgar or exhausting or effeminate’.38 All indecent language and improper pictures should be banished completely as children must be protected from all shameful sensations so that all morally blameworthy phenomena are foreign to the spirit of young people. ‘Between the ages of 5 and 7 they must be spectators of the lessons they will afterwards learn.’39

At the age of 7, the children enter school. Schooling continues up to the age of 21. It is divided into three periods of three years each. As only fragments of Aristotle’s work have reached us we cannot know in detail the features and structure of these three cycles of study. Nor do we possess any specific knowledge about adult education. However, the texts tell us explicitly that education is not completed at the age of 21:

But it is surely not enough that when they are young they should get the right nurture and attention: since they must, even when they are grown up, practise and be habituated to them, we shall need laws for this as well, and generally speaking to cover the whole of life.40

Aristotle’s education system is thus clearly a system of continuing education. We should also note that in Aristotle’s view ‘the body reaches maturity between the ages of 30 and 35; the soul by the age of 49′.41 It seems probable that these thresholds also marked stages in the comprehensive system of education devised by Aristotle.

When considering Aristotle’s system of continuing education one must not forget that his ideal city-like the Greek polis in general-is an educational city. Its citizens are required to perform different functions in the course of their lives; they must obey, order and judge. They participate in the service of the gods which is linked to initiation rites. They attend performances of tragedies. These go to make up a set of elements that contribute to continuing education. As we have seen, education was for Aristotle the affair of the state. Schools should be public. Here Aristotle, like Plato, was far ahead of his time. For the education of children in the Greek polis was a matter for the family. With the exception of physical education and military instruction, all forms of tuition were private. The introduction of public education always indicates a certain democratization of education. ‘Education must be one and the same for all.’42 But up to what age? Twenty-one? The texts do not tell us. But at no point does Aristotle mention selection, though he repeatedly emphasizes that moral and intellectual gifts are unevenly distributed. It is remarkable that Aristotle seems not to have prescribed any form of selection or competition in his system of education in a Greece which set a high value on all forms of competition.

Nevertheless, this democratic form of education has its limits in that it is reserved for the children of citizens. Although Aristotle does not say so explicitly, this seems obvious if we take into account the whole of the Ethics and the Politics. There is no access for the children of agriculturalists, artisans or retail traders. As for slaves, they are not considered as complete human beings in any case. But it seems probable that Aristotle prescribed some sort of vocational training for tradesmen as he quite frequently refers to the importance of a good apprenticeship for the proper practice of a trade. And in certain conditions he even prescribes a form of education for slaves: ‘Since we observe that education shapes the character of young persons, it is also essential, when one has acquired slaves, to provide education for those who are destined for liberal occupations.’43 The question of education for girls remains an open one. In Aristotle’s view, women are certainly not the equals of men. By their very nature they are destined to obey and are therefore not free. Their bodily and moral virtues are not the same as those of men. However, ‘individuals and the community should similarly endeavour to develop each of these [physical and moral] qualities in boys and girls’.44 It thus seems that Aristotle also envisaged public education for girls. Such education would be directed towards ‘beauty and greatness, chastity and a liking for work without greed’.45

We conclude, therefore, that education must be regulated by law, and that it must be controlled by the state. We must now deal with the nature and methods of public education. At present there is some difference of opinion about the subjects to be taught […] neither is it clear whether education should be more concerned with intellectual or with moral character!46

Aristotle thus poses the question of the content of education. Once again his answer has reached us only in fragments. And it appears that the parts which have been lost are precisely those which are the most original. In principle, young people should be instructed in ‘such useful acquirements as are really necessary. Occupations are divided into liberal and illiberal.’47 By ‘useful acquirements’ Aristotle means such subjects as grammar, arithmetic, drawing and physical training, but certainly not manual work or anything that could lead to paid work, which is described as menial. Furthermore, young people must be taught to fill their leisure time nobly. Hence: there are branches of learning and education which must be studied simply with a view to leisure spent in cultivating the mind. It is likewise clear that these studies are to be valued for their own sake, while those pursued for the sake of an occupation must be looked upon as no more than necessary means to other ends.48

Aristotle recognizes at least four subjects for instruction: grammar, physical training, music and drawing. InPolitics he elaborates his ideas on physical training and above all on music. He discusses drawing briefly but the section which should be devoted to grammar is completely absent. Yet this section must have been particularly interesting in view of the role played by language in Aristotle’s thought. We may suppose that grammar included the history of literature in addition to reading and writing (bearing in mind that Aristotle prepared a commentary on the Iliad for the young Alexander and that his texts abound in literary references). Did his grammar also contain the fundamentals of logic and mathematics? And what about the teaching of the natural sciences and philosophy? We have no clear answers to any of these questions. All we know for certain is that he was concerned with the teaching of the sciences, since he mentioned it on several occasions. We shall come back to this point.

Aristotle is faithful to his principle of the mean in what he says about physical training. This does not involve over-rigorous training or a brutal upbringing. Neither is it a matter of paramilitary instruction. For Aristotle physical training is not simply a matter for the body: it must help to form character, that is, courage and a sense of honour.

Clearly inspired by Plato, Aristotle deals at length with musical education. Even more than physical training, music is a means of influencing moral character. For this reason it is essential. Obviously one must be sure to concentrate on good music, for certain musical modes, rhythms and melodies are harmful to character. Like Plato, Aristotle analyses the Greek tonalities in this connection and expresses a preference for the Dorian mode, ‘that is the most solemn and sturdiest of modes’.49 It also stands midway between the other modes. Musical education is also important as pupils learn thereby to judge the beautiful. And it has a general educational value since it teaches them to listen. But music is the meanspar excellence of education for leisure. ‘Cultivation of the mind is universally acknowledged to contain an element not only of nobility, but also of pleasure, because felicity is compounded of both. Now all men agree that music […] is one of the greatest pleasures.’50

Teachers are an essential part of any education system but one about which the Aristotelian texts have nothing to say. It is particularly curious that when Aristotle lists the various public functions of the ideal state he makes no reference to the teacher. Likewise, when describing the general plan of the city, he has nothing to say about the location of the school.

Pedagogy

Politics ends abruptly with a remark on education: ‘Clearly, then, there are three standards to which [musical] education should conform. They are the mean, the possible, and the proper […].’ Like all his practical philosophy, Aristotle’s theory of education is grounded in good sense. Extremes and excess are above all to be avoided. The purpose of physical training should not be to produce champions at all costs. And musical education should be more concerned with the pleasure of listening to music than with virtuosity. The next point is that pupils should not be asked to do more than their ability permits. Thus young men should not be given lessons on political science as they have no experience in practical matters.51 In general, it is necessary to take account of the intellectual level of pupils as ‘argument [is] not powerful with all men’.52 Lastly, education should be limited to what is appropriate for the pupil, taking account of his age, character, and so on.

In accordance with man’s nature, which is composed of the body, the soul and reason, education should proceed in stages. ‘Care of the soul should be preceded by that of the body, which must be followed immediately by training of the appetites. This training, however, should be directed to the benefit of the mind, and care of the body to that of the soul.’53 Reason and intellect only begin to develop in the child from a certain age. Education should therefore begin with physical training, continue with music and conclude with philosophy.

Aristotle identifies two complementary educational categories: education through reason and education through habit. For Aristotle ‘education through habit’ does not mean a sort of training involving automatic repetition. What he understands by this expression is what we today would call ‘active learning’. Moreover, in the Nichomachean Ethics he emphasizes that ‘for the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them, e.g. men become builders by building and lyre-players by playing the lyre’.54 This is also true of moral education: ‘We become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts.’55 It is through habit or active learning that natural dispositions develop. But education through habit is not limited to the learning of arts and techniques, and to the development of moral attitudes, but also concerns scientific education. ‘It is through the practice of science that the possessor of science becomes learned in actuality.’56

For Aristotle, then, education is not something to which the pupil must passively submit. On the contrary, it is action that counts. Here too the theory of education faithfully reflects the main lines of Aristotelian philosophy as a whole. And this action is a source of pleasure for the pupil. Aristotle is clearly enough of a realist to see that young people are to be governed not only by pleasure but also by pain.57 There can be no doubt that Aristotle was a rather authoritarian educator!

Education through habit is connected with three notions which should be mentioned: imitation, experience and memory. Man likes to imitate; all the arts are based on an imitation of nature. But imitation is also an essential source of lessons and education. ‘Imitation is a distinctive feature of man from his childhood: imitation separates him from the animals and it is through imitation that he acquires his earliest knowledge.’58 But a good example is needed if imitation is to serve the cause of moral education: ‘Without a good example there can be no good imitation and that is true in all areas.’59 Some virtues and types of knowledge can only be acquired through experience. This applies to prudence, for example, but also to physics:

While young men become geometricians and mathematicians and wise in matters like these, it is thought that a young man of practical wisdom cannot be found. The cause is that such wisdom is concerned not only with universals but with particulars, which become familiar from experience, but a young man has no experience. […] one might ask this question too, why a boy may become a mathematician, but not a philosopher or a physicist. Is it because the objects of mathematics exist by abstraction, while the first principles of these other subjects come from experience, and because young men have no conviction about the latter, but merely use the proper language, while the essence of mathematical objects is plain enough to them?60

The effect of habit is based on the phenomenon of memory to which Aristotle devotes a text included in theParva Naturalia.61 He underscores the imaginative nature of memory and the importance of repeated acts of recollection.

Education through reason complements education through habit. It is education in the proper sense of the term including, specifically, the teaching of the sciences. Its aim is to impart an understanding of causes: ‘To teach is to indicate the causes of all things.’62 Education through reason is concerned with the universal, which surpasses experience. ‘Men of experience know that a thing is, but they do not know why it is, whereas men of learning know the reason and the cause.’63

Language is the essential instrument of education: ‘Language is the cause of the education which we receive.’64 For that reason, hearing has an important role. ‘The faculty of learning belongs to the person who possesses the sense of hearing as well as memory.’65 One recalls the role which Aristotle attributes to music in education. He draws a curious conclusion from the link between hearing and education, observing that it is for that reason that ‘blind people are more intelligent than the deaf and dumb’.66 The place of the problem of language in Aristotle’s philosophical thinking is well known. To a large extent his philosophy amounts simply to an analysis of the functions of language.

Education through reason is characterized by two methods: epagoge, or learning by induction, and learning by demonstration: ‘Indeed, we learn only through induction or by demonstration. […] Demonstration proceeds on the basis of universal principles and induction on the basis of particular cases.’67 Epagoge is the path that leads from experience to knowledge. Examples are particular experiences. Aristotle’s ‘epagogic’ pedagogy is a form of teaching which proceeds from examples to an understanding of causes, as in science, which is always a knowledge of the universal. For Aristotle ‘all teaching given or received by means of reasoning derives from pre-existing knowledge’.68 But this pre-existing knowledge is quite different from that discussed by Socrates. It is not the result of a prior vision of ideas. It is the perception of a concrete fact or knowledge of the term that signifies that fact: ‘The fore-knowledge required is of two sorts: sometimes what has to be presupposed is that the thing actually exists; sometimes it is the meaning of the term employed, which has to be understood; and sometimes both at once.’69 Education thus consists in learning the meaning of words, that is, of language, and advancing towards knowledge by studying examples.70

The theoretical sciences-mathematics, physics and theology-are chiefly taught by demonstration, that is, not on the basis of examples but starting from universal principles. That is the highest level of education through reason, which proceeds by means of syllogisms. Thus, to a great extent, education through reason coincides with the scientific approach or theoretical philosophy just as education through habit coincides with ethical action or practical philosophy. But the goal remains the same: happiness, the convergence of virtue and wisdom, the contemplative life of the philosopher or sage.

Conclusion

Although Aristotle’s work has reached us in incomplete form and many important texts are missing, his theory of education can be seen to occupy an important place in his philosophical thinking as a whole. If the goal of man is one of his essential concerns, it is only through education that man fulfils himself completely. Human beings possess specific natural aptitudes but it is only through education that they learn the business of being human and become truly human: ‘It is precisely [nature’s] deficiencies which art and education seek to make good.’71 It is through education that culture is created. Aristotle’s theory of education has lost none of its relevance. His observations on educational policy and its role in society, his concept of a system of continuing education and education for peace and leisure, and his educational ideas have much in common with the concerns of those responsible for education today.

Notes

The quotations from Politics are taken from the translation by John Warrington for Everyman’s Library, London, Dent & Sons, 1959; those from the Nichomachean Ethics are from the translation by Sir William D. Ross in `The World Classics’ series, London, Oxford University Press, 1954, reprinted in 1963.

1. Charles Hummel (Switzerland). Studied philosophy at the Universities of Basle (with Karl Jaspers), Rome and Zurich. Permanent delegate of Switzerland to UNESCO (1970-1987). Member of the Executive board of UNESCO. Member (and President) of the International Bureau of Education (IBE). Representative of Switzerland to the Council for Cultural Cooperation (Strasbourg). Ambassador to Ireland (1987-1992). Author of Nicholas de Cuse and Education Today for the World of Tomorrow and numerous articles on philosophical and educational subjects.

2. For example, On the Soul, III, 7, 431 a 16; On Memory and Reminiscence, III 449 b 31.

3. W.D. Ross, Aristotle, London, Methuen, 1968, p. 7.

4. Diogène Laërce, Vie, doctrines et sentences des philosophes illustres, Paris, Flammarion, 1965, V, 1, 2.

5. J. Burckhardt, Griechische Kulturgeschichte, vol. IV, Berlin, 1898, p. 397.

6. P. Bamm, Alexander oder die Verwandlung der Welt, Gesammelte Werke, Geneva, Edito-Service, 1975, p. 411.

7. This generally accepted fact is disputed by Ingemar Düring, Aristoteles (Heidelberg), Winter 1966, p. 13.

8. Ross, op. cit., p. 7.

9. Nichomachean Ethics, I, 10, 1099 b 11-12.

10. Ibid., I, 11, 1100 b 9-10.

11. Ibid., I, 13, 1103 a 4-5.

12. Ibid., II, 1, 1103 a 14-19.

13. Ibid., II, 1, 1103 b 23-25.

14. Ibid., X, 10, 1180 a 14-16.

15. Politics, II, 13, 1332 a 35.

16. For example, in Politics, VIII, 7, 1342 b 14-15: `and so long as we hold that extremes should be avoided in favour of the mean and we declare that it is this mean that we should pursue [in education]’.

17. Politics, VIII, 7, 1342 b 32.

18. Ibid., VII, 14, 1333 a 30 sq.; VII, 15, 1333 b 15.

19. Nichomachean Ethics, X, 7, 1177 b 4.

20. Politics, VII, 14, 1333 b 3.

21. J. Tricot’s translation of Politics, Paris, Vrin, p. 528, note 2; see also Düring, op. cit., pp. 481 sq.

22. Politics, I, 13, 1260 a 42.

23. Ibid., III, 4, 1277 b 3-6.

24. Ibid., VIII, 6, 1341 a 17.

25. Ibid., VIII, 6, 1341 b 8-14.

26. Ibid., I, 2, 1253 a 26-28.

27. Ibid., II, 5, 1263 b 36-37.

28. Ibid., I, 2, 1252 b 30.

29. Ibid., VII, 13, 1332 a 31.

30. Ibid., V, 9, 1310 a 12-17.

31. Ibid., V, 9, 1310 a 18.

32. Ibid., VIII, 1, 1337 a 10-20; see also Nichomachean Ethics, X, 10, 1180 a 34-35.

33. Ibid., VII, 15, 1334 a 15.

34. Ibid., VII, 14, 1333 a 31 b 4.

35. Nichomachean Ethics, VIII, 13, 1161 a 17-18. The same idea is also to be found in Economics, I, 4, 1344

36. Politics, VII, 16, 1335 a 5.

37. Ibid., VII, 16, 1335 b 12.

38. Ibid., VII, 17, 1336 a 28.

39. Ibid., VII, 17, 1336 b 35.

40. Nichomachean Ethics, X, 10, 1180 a 1-4.

41. Rhetoric, II, 14, 1390 b 9.

42. Politics, VIII, 1, 1337 a 22.

43. Economics, I, 5, 1344 a 27.

44. Rhetoric, I, 5, 1361 a 8.

45. Ibid., I, 5, 1361 a 6.

46. Politics, VIII, 2, 1337 a 32-49.

47. Ibid., VIII, 2, 1337 b 5.

48. Ibid., VIII, 1338 a 10-13.

49. Ibid., VIII, 7, 1342 b 13.

50. Ibid., VIII, 5, 1339 b 18-21.

51. Nichomachean Ethics, I, 1, 1095 a 2.

52. Ibid., X, 10, 1179.

53. Politics, VII, 15, 1334 b 26-27.

54. Nichomachean Ethics, II, 1, 1103 a 33; Metaphysics, O, 8, 1049 b 30-33.

55. Ibid., II, 1, 1103 b 1-2.

56. On the Soul, II, 5, 417 b 5.

57. Nichomachean Ethics, X, 1, 1172 a 20.

58. Poetics, 4, 1448 b 4-9 (quoted in p. Somville, Essai sur la Poétique d’Aristote et sur quelques aspects de son posterité, Paris, J. Vrin, 1975, p. 44).

59. Economics, I, 6, 1345 a 9.

60. Nichomachean Ethics, VI, 9, 1142 a 12-20.

61. On Memory and Reminiscence, I, 449 b 4 sq.

62. Metaphysics, A, 2, 982 a 30.

63. Ibid., A, 1, 981 a 28-29.

64. De Sensu, I, 437 a 12.

65. Metaphysics, A, 1, 980 b 25.

66. De Sensu, I, 437 a 16.

67. Posterior Analytics, I, 18, 81 a 39-40.

68. Ibid., I, 1, 71 a 1.

69. Ibid., I, 1, 71 a 11-12.

70. See on this subject the analysis by Gunther Buck, Lernen und Erfahrung, 3rd ed., Darmstadt, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1989, p. 28 ff.

71. Politics, VII, 17, 1337 a 2.

Further reading

The literature on Aristotle is enormous, although books which examine the educational thoughts of the philosopher are somewhat rare. The following selected bibliography only contains those publications which deal with Aristotle the educator at some length and to which I have referred.

- Aubenque, p. Aristote et le Lycée. In: Histoire de la philosophie, Encyclopédie de la Pléiade. vol. I.Paris, Gallimard, 1969.

- Barreau, F. Geschichte der Pädagogik. Heidelberg, Quelle & Meyer, 1968.

- Blättner, H. Aristote et l’analyse du savoir. Paris, Seghers, 1972.

- Braun, E. (Herausg. und Übersetzer). Aristoteles und die Paideia. Paderborn, Ferdinand Schöningh, 1974.

- Düring, I. Aristoteles. Darstellung und Interpretation seines Denkens. Heidelberg, Carl Winter Universitätsverlag, 1966.

- Gauthier, R.-A. La morale d’Aristote. Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1973.

- Hamelin, O. Le système d’Aristote. Paris, J. Vrin, 1976.

- Jaeger, W.W Aristotle: Fundamentals of the History of His Development. 2nd. ed. Trans. by R. Robinson. New York, NY, AMS Press, 1948.

- Louis, p. La découverte de la vie. Aristote. Paris, Hermann, 1975.

- Pietri, C. Les origines de la `pédagogie’. Grèce et Rome. In: Histoire mondiale de l’éducation. vol. I. Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1981.Ross, W.D. Aristotle. London, Methuen, 1968.

- Ruggiero, G. de. La filosofía greca. Bari, Laterza, 1946.

- Sandross, E.R. Aristoteles. Stuttgart, Kohlhammer, 1981.

Copyright notice

This text was originally published in Prospects (UNESCO, International Bureau of Education), vol. XXV,no. 3, September 1995, p. 535-51.

Reproduced with permission. For a PDF version of the article, use: http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/archive/publications/ThinkersPdf/aristote.pdf

Photo source: Clendening Library Portrait Collection