Government Performance Management in Vietnam

Located in the heart of South East Asia, The Socialist Republic of Vietnam has experienced a steady economic growth during the last twenty-five years. Starting from the late 1980s, the central government has initiated a vast array of economic reforms, commonly known as “Đổi Mới´” (open door) with the objective of moving the country away from a centrally planned economy, penalized by large-scale production, trade deficits and hyperinflation, back to a market oriented one.

The implementation of such policies were enacted by the Sixth Party Congress in December 1986. The Congress agreed on the need for policy reforms aimed at reducing the macroeconomic (and political) instability that characterized the country along with accelerating the economic growth using monetary and economic policies at price, wages and fiscal level.

The Đổi Mới has had a significant impact on the country, both on the individual level, in terms of personal welfare, for instance, average annual income has been boosted from US $ 150 in 1985 to US $ 2000 in 2015, as well as in regards to country welfare, as it has made Vietnam a global economic player.

Along with China, Vietnam has been considered one of the powerhouses, in an economic development sense, of Asia. However, despite the noticeable improvement in the status of the economy, along with a guaranteed stability as opposed to the country’s turbulent past, there have been growing pains along the way, starting from the increasing disparity in income distribution, widespread poverty especially in rural areas, as well as corruption across all levels of the government structure.

Moreover, according to the World Bank’s “2016 Ease of doing business index”, Vietnam was ranked 90th (decreasing from 2015’s 82nd) out of 189 surveyed economies.

Overall, despite the above-mentioned challenges faced by the country, there is much to be positive about the evolution of the Vietnamese economy, above all when considering where the country came from just two decades ago.

In more recent times, with Vietnam’s ratification of the Trans Pacific Partnership along with the signing of free trade deals with the European Union, analysts predict that these deals could fuel a further boost to the Vietnamese economy for the next decade, through its export-intensive activities.

Considering the forecasted economic benefits at stake, the Vietnamese government has talked about the introduction of a Performance Management System aimed at monitoring and achieving the strategic objectives laid out during the launch of the Ninth Five-Year-Economic-Plan for the years 2016-2020. In the plan they have announced, eight economic indicators have been assigned targets:

- Average annual GDP growth between 6.5% and 7.0%;

- GDP per capita between US $ 3,200 and US $3,500 in 2020;

- Industry and Services to account for 85% of GDP in 2020;

- Total Social Investment Capital between 32% and 34% of GDP in 2020;

- State budget deficit of 4% of GDP in 2020;

- Fall in energy consumption as a % of GDP of between 1% and 1.5% per year;

- Urbanization rate of between 38% and 40% by 2020;

- Total Factor Productivity contributing 30% to 35% of growth, with labor productivity increasing 5% per year on average.

Vietnam’s Provincial Governance and Public Administration Performance Index

The Performance Management System developed by the Vietnamese government rests on the concept called PAPI.

PAPI, introduced by the Government in 2009, is a policy monitoring tool, created in collaboration with the Center for Community Support Development Studies (CECODES) under the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), to reliably assess citizens’ experiences and satisfaction with governmental performance at the national and sub-national levels.

This PMS aims at improving the performance of local authorities to meet their citizens’ needs in two ways:

- Creating constructive competitions and promotes learning among local authorities;

- Enabling citizens to benchmark their local or provincial governments’ performance and advocate for improvements.

Since its introduction, the PAPI survey has captured and reflected the experiences of nearly 100,000 citizens with diversified demographic and educational backgrounds.

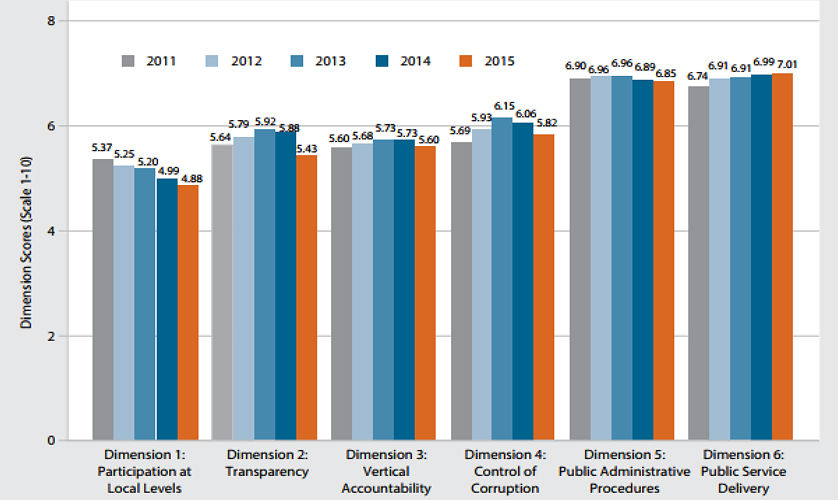

By reeling in citizens’ feedback about government performance and policy making, PAPI helped build a performance culture within national and provincial governments to support better policy making, management of public resources and public service delivery. The Index showcases an overview of nationwide performance by measuring six dimensions, composed of 22 sub-clusters and by monitoring 90 Key Performance Indicators. The dimensions are the following:

- Participation at Local Levels – composed of 4 sub-dimensions, measuring 18 KPIs (e.g. % Participation in village head election, % Voluntary contribution to project);

- Transparency in Local Decision-Making – composed of 3 sub-dimensions, measuring 15 KPIs (e.g. # Poverty lists published, % Public awareness of local land plans);

- Vertical Accountability – composed of 3 sub-dimensions, measuring 11 KPIs (e.g. # Interactions with local authorities, % Contacted village head);

- Control of Corruption in the Public Sector -composed of 4 sub-dimensions, measuring 12 KPIs (e.g. % Public agree no bribes for State Employment);

- Public Administrative Procedures – composed of 4 sub-dimensions, measuring 16 KPIs (e.g. % Applied for construction permit, % Received land title);

- Public Service Delivery – composed of 4 sub-dimensions, measuring 18 KPIs (e.g. % Population with health insurance, % Access to drink tap water).

Since its introduction, the PAPI Index has received broad-based political support from the National Assembly Ministries and provincial governments, becoming a very useful tool for policymakers to effectively tailor new policies to meet citizen’s needs. In 2015, the initiatives taken by the national government have yielded improved performance especially in the delivery of public services and in a stricter control of corruption.

However, there is still room for improvement, as most noticeably the transparency dimension declined sharply, more than 7% in 2015 compared to previous years. Another problematic area is the decline in citizen participation in political life and policymaking, reaching an all-time low, since 2009.

PAPI has now been implemented nationwide for six consecutive years. The year 2015 witnessed declines across almost all the dimensions, as compared to previous years, a complete overview of the 2015 Performance results can be seen here:

As it can be seen, Public Service delivery is the only dimension that experienced an improvement in performance. These declines could be due to changes in the way the PAPI survey was conducted, including the introduction of survey administration technology, new training protocols, but above all new questions. With such changes, fewer respondents participated in the 2015 survey, compared to the 2014 results.

This could have influenced the results in the transparency dimension. Respondents who had already participated in the survey might see it as a source of information that encourages citizens to press officials for further information on the budget or land development plans, leading to overall improvements in their assessment of transparency, in the following years. However, with fewer respondents during 2015, transparency was rated poorly compared to previous years.

Implications for the future

The Government of Vietnam has introduced the PAPI Index, with the objective of developing its own system of Government Performance Management. During the last 5 years, the survey has experienced changes in the structure, methodology and delivery.

Although it is not clear how much of the PAPI indicators created as a result of citizens’ responses will be a part of the government performance management system, it is noticeable that Provincial Governance and PAPI Reports have fueled an appetite in the country towards the utilization of a bottom-up perspective of government performance.

Along with the PAPI Index, the Ministry of Home Affairs is currently developing, even though it is still in pilot mode, a second index called the Public Administration Reform (PAR) Index, which will target both Ministries and ministry-level agency performance, province and centrally-affiliated city performance, and the Provincial Competitiveness Index (PCI) which measures businesses’ experiences with provincial economic governance.

Assessing what has been done so far, the Vietnamese government is acting fast in order to create a PMS framework that would enable them to help national, local and provincial governments to perform better, through the application of a holistic approach, with clear priorities, milestones, outputs and outcomes assigned to face the identified challenges.

With the citizens’ feedback mechanism in place via PAPI and PCI, Vietnam is confirming its commitment to building a strong, responsive and accountable government system, in preparation for the realization of the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development.

Image sources:

Tags: Government performance, Performance in Vietnam