An introduction to theory in Performance Management: Agency theory and its link to pay for performance arrangements

smartKPIs.com Performance Architect update 13/2010

Agency theory has its origins in the research conducted by economists in the 1960s and 1970s, exploring risk sharing among individuals and groups, such as the relationship between insurers and customers. Gradually the scope of investigation expanded from risk to cooperation and division of labour between parties with different goals (Eisenhardt, 1989). As a result of this process, agency theory or the principal-agent problem addresses the relationship of agency, one of the oldest forms of social interaction. It was described eloquently in one of the first academic articles on the subject: “…an agency relationship has arisen between two (or more) parties when one, designated as the agent, acts for, on behalf of, or as representative for the other, designated as principal…” (Ross, 1973). The relationship between employer and employee, doctor and patient or between government and the governed are representative examples.

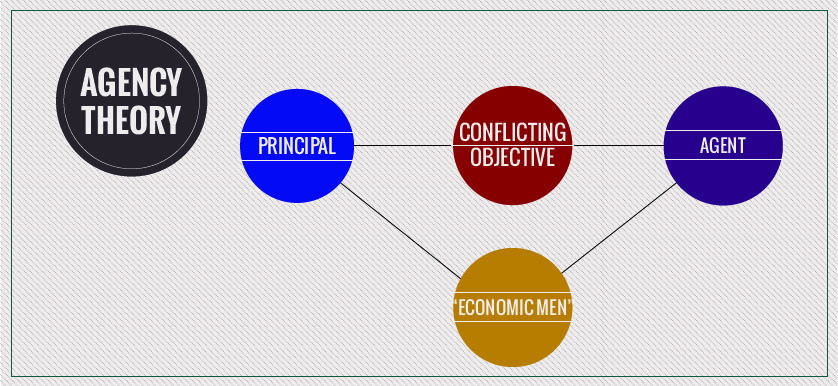

The theory was discussed in great detail by Eisenhardt in a series of articles published in mid to late 1980s, providing more clarity regarding the application of this theory in organizations. In an organizational context the agency theory explains how to best organize relationships in which one party (the principal) determines the work, which another party (the agent) undertakes. (Eisenhardt, 1985). The implications for performance management as a discipline are considerable, as in organizational context, the objectives of individuals, teams and the entity as a whole can be in conflict. Goal conflict can motivate incompatible actions and this has the potential to impact performance. Thus, alignment between individual and group objectives is important for maximising performance.

The challenge is balancing and harmonising the interests of the principal (employer) and the agent (employee). The settings in which the agency theory is defined in an organizational context are:

- Organizations are composed of a complex network of relationships between individuals and entities with conflicting objectives.

- Both the principal (i.e. employer) and the agent (i.e. employee) are wealth seeking “economic men” who pursue their own self interest (Tiessen and Waterhouse, 1983)

Eisenhardt (1985) presents the theory in two cases. The first one is characterised by complete information, when the behaviour of the agent is observed and the actions and motivations are transparent. The solution to this scenario is a behaviour based contract purchasing of services. However, such a scenario is less frequent due to the information asymmetry problem.

The second case is characterised by incomplete information. In this case, a fixed wage might create an incentive for the agent to avoid efforts and responsibilities since his compensation will be the same regardless of the quality of his work or his effort level (Eisenhardt, 1985). The principal has limited information regarding the level of effort and the behaviour of the agent. This generates a number of issues:

- The utility function of the agent is in contradiction to the one of the principal. In a company, the employer is interested in maximizing productivity and profit. Employees however may have their own agendas, sometimes being maximizing the benefits from the association with the organization (revenues, training, and status) with minimum effort.

- There is an information asymmetry between the principal and agent. The underlying behaviour motivations of both employer and employee are not clearly expressed and balanced. What makes this problem more challenging is that such motivations change continuously.

- Moral hazard, as the principal can’t determine the effort level employed by the agent and cannot be sure if the agent has put forth maximal effort (Eisenhardt, 1989).

- Adverse selection, as agents may claim their skills and experience level is higher than the actual one. The principal cannot ascertain if the agent accurately represents his ability to do the work for which he is being paid (Eisenhardt, 1989).

- The difference between principal and agent in terms of attitude towards risk. Often the principal is assumed to be risk neutral while the agent risk adverse (Tiessen and Waterhouse, 1983).

Possible solutions for such are scenario are:

- Increasing the quality and quantity of information related to the behaviour of the agent. This can be done through increasing the level of management, physical surveillance and establishment of control mechanisms such as budgeting systems (Eisenhardt, 1985). However it is costly and most often impractical to address the information asymmetry problem. Options such as surveillance may raise privacy and ethical issues and are not always suitable and most of the time not welcomed by the agent. The problems of adverse selection and moral hazard mean that fixed remuneration contracts are not always the ideal solutions to organize relationships between principals and agents (Jensen and Meckling, 1976).

- A second option is rewarding the agent based on outcomes by using arrangements such as: commissions, profit sharing, bond posting by the agent and leveraging the fear of firing. . The provision of ownership rights reduces the incentive for agents’ adverse selection and moral hazard since it makes their compensation dependent on their performance, which includes risk sharing (Fama and Jensen, 1983). The disadvantage of such an approach is that the agent may be penalised or rewarded for results that were influenced by non-controllable, external factors: good outcomes may be produced despite poor efforts and poor outcomes may occur despite good efforts from the agent, to whom some of the risks of the firm are transferred (Eisenhardt, 1985).

Overall, the principal-agent relationships should reflect efficient organization of information and risk-bearing costs. The human assumptions to be considered are self interest, bounded rationality and risk aversion, while at organizational level the assumptions to be analyzed are the goal conflict among participants and the information asymmetry.

While analysis of the theory can be done at macro level, the solution of the problem is specific to each organization. It is influenced by the environment in which it operates and the internal characteristics, such as resources available and structure of organizational systems.

Performance management systems are generally employed to help address the problem. However, this should be noted as one of the contributions such systems bring to organizations. Using such systems to address the agency problem limits their potential and if not configured properly may cause additional issues. This should be a good enough incentive to explore the theory that informs performance management as a discipline before using systems and tools without a clear purpose.

Stay smart! Enjoy smartKPIs.com!

Aurel Brudan

Performance Architect, www.smartKPIs.com

References

- Eisenhardt, M, K. (1989), “Agency theory: An assessment and review”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 57-74.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1985). “Control: Organizational and economic approaches”, Management Science, Vol. 31, Nr. 2, pp. 134-149

- Fama E. F. and Jensen M. C., “Agency Problems and Residual Claims”, Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 327-349

- Jensen, M.C., and W.H. Meckling (1976), “Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 3., No. 4, pp. 305−360.

- Ross, Steven, (1973). “The economic theory of agency: The principal’s problem”, American Economic Review, Vol. 63, No.2, pp. 134-139.

- Tiessen, P., J.H. Waterhouse (1983), “Towards a descriptive theory of management accounting”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 8 pp.251 – 267

Tags: Aurel Brudan, Performance Architect Update, Performance Management Theory