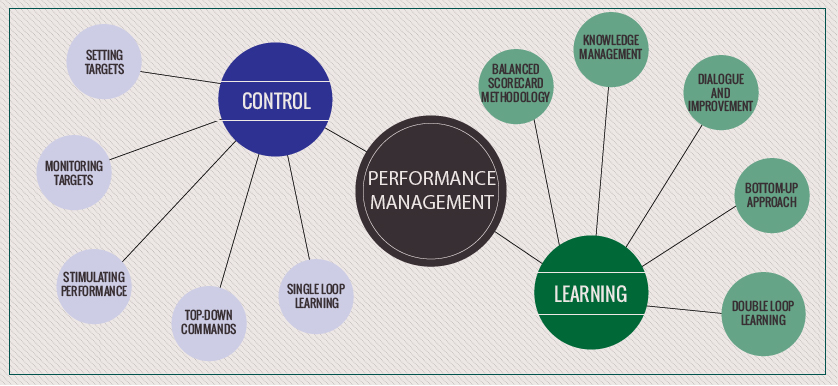

From performance management for control to performance management for learning

smartKPIs.com Performance Architect update 28/2010

The following is an excerpt from a conference paper presented at the 2009 Performance Measurement Association Conference in Dunedin, New Zealand. An edited version of the paper was published in the Measuring Business Excellence Journal in 2010 (vol. 14, No. 1), under the title: “Rediscovering performance management: Systems, learning and integration“.

Traditionally, organisational performance management has been concerned with control, by setting and monitoring achievement of targets at strategic, operational and individual levels. Measurement has its benefits as it provides valuable information and measuring in itself stimulates higher performance. The Hawthorn effect and the Westinghouse effect or “Observer’s paradox” (Cukor-Avila, 2000) demonstrate the delicate nature of the measuring process and the impact that measurement itself has on the results.

At strategic level, senior management supported by management accountants and finance professionals focus their efforts in translating organisational objectives in quantifiable targets. These objectives and targets are delegated to functional areas for implementation. Compliance with set targets is checked on a regular basis. These strategic objectives are then aligned with operational objectives and individual performance objectives. However, empirical evidence shows that the focus on the measurement and control in the context of performance management has started to diminish in the 1990s, driven by the increase in popularity of the Balanced Scorecard (BSC), Knowledge Management and Systems Thinking. Even the BSC was first presented in 1992 as a measurement tool promoted by the management accounting school and having roots in the quality movement. However it evolved quickly to become a complete management system supporting strategy implementation as a core competency. As a performance management concept, the BSC enables not only measurement and control, but also communication and learning.

This shift is supported by proponents of the knowledge management/intellectual capital school of thought who argue that “the main problem with all measurement systems is that it is not possible to measure social phenomena with anything close to scientific accuracy” (Sveiby and Armstong, 2004). They invoke Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle to illustrate the inherent imprecision in measurement that exists even in “exact” sciences such as physics. The principle states that uncertainties, or imprecision, always turn up if one tries to measure the position and the momentum of a particle at the same time (Cassidy, 1993, 1998). Neils Bohr famously stated that “Accuracy and clarity of statement are mutually exclusive” (for further details see Pais, 1994).

Measurement for rewards leaves room for interpretation in the process of setting targets and measuring results and quite often leads to abuse. Using targets for control and linking the achievement of these targets to individual performance has the risk of staff members manipulating the system to their benefit and the expense of other teams and even the entire organisation.

The alternative proposed to measurement for control is measurement for learning, as illustrated by the table below:

| Characteristic | Measurement for control | Measurement for learning |

| Measurement drivers | Management | Employees |

| Measures development | Top-down commands | Process-oriented bottom-up approach |

| Measurement role | Measuring and managing work in functional activities. | Measuring and managing the flow of work thought the system |

| Measurement focus | Productivity output, targets, standards: related to budget | Capability, variation: related to purpose |

| Results communication | Restricted | Open |

| Target driven by | Budget/political aspirations | Understanding achievement versus purpose |

| Follow-up to results | Rewards, punishment and action to improve results | Dialogue and improvement |

| Learning cycle | Single loop | Double loop learning |

| Link to rewards | Link to individual rewards and recognition system | Group rewards, based on improvement |

Table: Measurement for control compared to measurement for learning, Brudan, 2010

A mechanistic view on performance management, focused on measures and targets in isolation, pay-for-performance, control and rhetoric leads frequently to unoptimized results. Opposed to this is a Systems Thinking based view on managing performance, that coupled with the emphasis on learning, highlight the need for an integrated approach to performance management. Effective performance management requires more than measuring and reporting in isolation, more than control and rewards. It requires an organic performance architecture, that values more performance management for learning is informed by a more humanistic performance philosophy.

Stay smart! Enjoy smartKPIs.com!

Aurel Brudan Performance Architect, www.smartKPIs.com References- Brudan A.N. (2010) “Rediscovering performance management: systems, learning and integration”, Measuring Business Excellence, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 109-123.

- Cassidy, D. (1993) “Uncertainty: The Life and Science of Werner Heisenberg”, W. H. Freeman, New York, pp. 226-246.

- Cassidy, D. C. (1998) “Answer to the Question: When Did the Indeterminacy Principle Become the Uncertainty Principle?” American Journal of Physics, Nr. 66, pp. 278-279

- Cukor-Avila, P. (2000) “Revisiting the Observer’s Paradox”, American Speech, Vol.75, Nr. 3 pp. 253-254.

- Pais, A. (1994), “Niels Bohr’s Times: In Physics, Philosophy, and Polity”, Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, pp. 304-309.

- Sveiby, K. E. and Armstrong C.(2004). “Learn to Measure to Learn!”, opening keynote address at the Intellectual Capital Congress Helsinki, 2 Sept 2004.

Walker, Rob 1992, “Rank Xerox – Management Revolution”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 9 to 21

Tags: Aurel Brudan, Education and Training performance, Performance Architect Update, Systems thinking