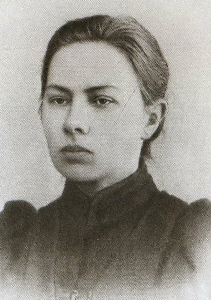

Nadezhda, Krupskaya (1869-1939)

An article written by Mihail S. Skatkin 2 and Georgij S. Cov’janov 3

Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya, the outstanding stateswoman and party activist, wife and companion of Lenin, stands at the source of Marxist-Leninist educational science. Her pedagogical legacy embraces practically all aspects of education policy, from the basic principles for the organization and management of schools, the content of education and teacher training, to adult education, eradication of illiteracy, and children’s and youth movements.

Krupskaya is renowned in many countries the world over as a theoretician and historian of educational science and as one of the main organizers of the socialist system of education.

UNESCO’s international Nadezhda K. Krupskaya Prize and diploma are tokens of the high esteem in which her work is held; they are awarded annually to countries, institutions, organizations and individuals for outstanding achievements in the eradication of illiteracy.

A life history

N.K. Krupskaya was born in Petersburg on 14 February 1869. Her parents were descended from poor landowners and shared the views of the progressive revolutionary democratic intelligentsia of the day, a fact that naturally helped to shape a progressive world view in this lively and inquisitive girl. ‘Already in those days’, N.K. Krupskaya subsequently wrote, ‘I heard a great deal of revolutionary discussion, and my sympathies were of course with the revolutionaries’ (Vol. I, p. 9).4

From her early youth Krupskaya was interested in the teaching profession. She completed her secondary education in 1886 with flying colours and began her year of teacher training. On completion of her studies, however, she could find no primary teaching post in either town or country. Compelled to tutor and give private lessons in the upper forms of a boarding school, the young teacher evinced great teaching ability, formidable learning and a conscientious attitude to her work. In 1891 she became a teacher at the workers’ Sunday evening school in Petersburg.

Krupskaya concentrated her attention on the social contrasts and upheavals of life and began to look for the causes of the injustice that prevailed, and for ways of removing it. She was an enthusiastic reader of works on society by Russian and foreign authors, and she studied the works of the founders of scientific communism, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Krupskaya joined the revolutionary movement in 1890, becoming a member of a Marxist student society. She engaged in revolutionary activity with the workers in conversation and in classwork, and acquainted herself with their living and working conditions. ‘My five years in the school’, she recalls, ‘breathed life into my Marxism and welded me to the working class’ (Vol. I, p. 37).

In 1895, Krupskaya joined the St Petersburg League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class, founding by V.I. Ulyanov (Lenin) and thereafter for almost half a century dedicated all her energy and learning to the work of the party, the service of the people and the revolutionary transformation of society. She took part in the preparations and meetings of party congresses and conferences, and devoted a great deal of attention to the publication and distribution of party literature.1

In spite of her innumerable commitments, the constant persecution, arrests and terms of exile, the level of education became an organic part of her revolutionary concerns. ‘The time will come’, she wrote in 1910, ‘when it will be possible to set up the kind of school the rising generation needs. We will have to know how to set up such a school, and for that we need experience, and we need to work on it in advance in order to understand how to approach the task’ (Vol. I, p. 142).

She made a thorough study of the work of such outstanding educationists of the past and of her own day as Y.A. Komenskii (Comenius), Jean-Jacques Rousseau, J.H. Pestalozzi, K.D. Ushinskij, L.N. Tolstoy and John Dewey5, and of the system of education in Russia and abroad—in the United States, England, France, Germany, Switzerland and other countries. She took advantage of her enforced emigration to acquaint herself with schools, libraries, teachers and the vanguard of educational experience. This enabled her to make a critical analysis of the state of education in the world, to select the best of educational theory and practice, and on that basis to ‘establish as precisely as possible the Marxist position with regard to schooling’.

By the time of the October Revolution, Krupskaya had already produced more than forty publications. The greatest of them, Public Education and Democracy (completed in 1915 and published in 1917), made an important contribution to the development of Marxist educational science. In Lenin’s estimation Krupskaya’s monograph offered a new interpretation, from the viewpoint of the working class, of the great democratic educationalists Rousseau and Pestalozzi, and was the first to acquaint Russian society with the educational ideas of Bellers and Owen, setting out in a systematic way the teaching of Marx and Engels on the link between education and productive labour. Drawing on a wealth of documentation, she showed how the substance of the idea of labour education changed in various phases of history in accordance with the class and conditions that shaped it. The concluding paragraph of the book serves as a summary of the analysis of labour education’s history: ‘As long as the organization of schooling stays in the hands of the bourgeoisie, labour school will be a weapon directed against the interests of the working class. Only the working class can turn labour school into “a tool for the transformation of contemporary society”.’

The triumph of the Socialist Revolution opened a wide range of educational activity to Krupskaya. She did a great deal of organizational, political and educational work; was deputy to the People’s Commissar (Minister) of Education; for many years was in charge of elaboration of the pedagogical aspects of the new system of education, and edited the journal Towards a New Life. In those years Krupskaya was chosen to be a delegate to all the party congresses; she was a member of its directing organs, a deputy of the higher organs of government and, from 1937, a member of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union.

Krupskaya skillfully and effectively combined her work in government, party and education with her scientific and literary endeavours. In the course of her life she published upwards of 3,000 books, pamphlets, articles, reviews, etc. (a collected edition of her works in eleven volumes has appeared). Much of her work has been translated into foreign languages and the languages of the peoples of the Soviet Union.

The quality of Krupskaya’s work in many fields has been acclaimed by the Soviet state. She was awarded the order of the Red Banner of Labour (1929) and the Order of Lenin (1933); in 1931 she was made an honorary member of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR and in 1936 she was awarded a doctorate of pedagogical sciences.

N.K. Krupskaya died on 27 February 1939. Her ashes lie in the Kremlin wall next to the Lenin mausoleum in Red Square in Moscow.

The construction of socialist education

The October Revolution brought opportunities for revolutionary reconstruction of education.

Problems of great historical importance had to be solved, and the educational monopoly of the 2 propertied classes had to be broken; it was necessary to overcome the cultural backwardness of Russia and arrange for the greatest possible number of workers to be introduced to politics, learning and aesthetic values.

Her knowledge of educational science and her organizational skills put Krupskaya on a par with A.V. Lunacharsky and M.N. Pokrovsky as a founder of the radically new, socialist system of public education. The first step in that direction, as Krupskaya wrote in 1918, had to be ‘the destruction of the old, class-ridden school system, which had become scandalously unjust, and establishment of schools that would satisfy the requirements of the rising socialist order’ (Vol. 2, p.

17). For her, the role of the new kind of school was the formation of fully-developed people with an integral view of the world and a clear understanding of what was happening around them in nature and society; people prepared at the theoretical and practical levels for any physical or intellectual work, and able to build a rational, full, beautiful and joyful life in society (Vol. 2, p. 11).

Such aims for education naturally called for the establishment of a single, all-embracing education system. When the Soviet authorities put all the country’s educational establishments under the control of the People’s Commissariat it became possible to open the doors to all the working masses, whatever their social status, nationality, creed or sex, and at the same time to establish genuine continuity between primary, secondary and higher education.

Of course, it was not easy to build a consistently democratic system of public education on the ruins of the old system, and the process was impeded by destruction and famine, the civil war unleashed by counter-revolutionary forces, foreign intervention, and mass illiteracy. The old textbooks were done away with, but new ones had not yet been written; the production of educational supplies and equipment had not been put in order; there were not enough school buildings and existing ones were not heated; a significant proportion of the teachers, of whom even earlier they had not been nearly sufficient, were moved by representatives of the old regime to sabotage the new system, and at first no new teachers were available to replace them. ‘Yet in spite of all those difficulties’, Krupskaya wrote in 1918, ‘the development of public education is set on course and will soon take the definite organizational forms that life itself dictates’ (Vol. 2, p. 38).

The key to success was in total support for party and government policy from the mass of workers and peasants with their thirst for knowledge. The organization of education became a matter for the whole people: community soviets for public education were set up everywhere, and parents’

committees were organized in schools.

A decisive role in the socialist reconstruction of education, however, was assigned to the teacher. The fact that not all of them were capable of understanding the essence of the revolutionary changes taking place in the country and the new tasks for schools was not so much their fault as their loss. Krupskaya observes (Vol. 2, p. 57):

In fact the people’s teacher is close to the people’s environment, and in most cases is connected with it in a thousand ways; the divide between the teaching profession and the people was artificially created, for a specific purpose. The new conditions are abolishing this divide, and forms of collaboration between teacher and population must be established that put an end to the unnatural division […] this rapprochement will ensure that schools flourish, and that through hard work together the cultural level of the country will rise, and that we will have a better future; it promises a renaissance of the teaching profession, whose role can now become honoured and respected.

Much was done in the Soviet Union to encourage teachers to take on the new tasks, to stimulate them with a fresh formulation of pedagogical problems, to improve their material situation and enhance their social status. Courses, seminars, teaching methods groups and other associations were formed throughout the country for the retraining of older teachers; a vast network of training institutes for teachers in secondary and higher education.

The illiteracy of a considerable part of the adult population, a legacy of the old regime, constituted another, no less difficult, obstacle to the establishment of education for all. Krupskaya 3

saw the eradication of illiteracy as a priority for Soviet education since ‘economically and culturally we can develop no further without dispelling the darkness of illiteracy’ (Vol. 9, p. 226). In 1919 the government issued a decree on the eradication of illiteracy in the 8 to 50 age group; 1920 saw the creation of the all-Russian Extraordinary Commission for the Eradication of Literacy, whose role was to concert the efforts of all organizations concerned with literacy education; in 1923 a voluntary organization called Down With Illiteracy! was formed. Its slogan, ‘Literate, Teach the Illiterate!’ brought young students, teachers and large sections of the intelligentsia to participate in the work. The result was that between 1920 and 1940 some 60 million adults were taught to read and write.

In 1925 the Soviet government began to establish general, free, compulsory primary education, which led to a sharp reduction in mass illiteracy. There were no more illiterates in the rising generation. The network of primary schools expanded rapidly. Primary-school enrolment in 1929-30 was double that of 1914-15. In the national republics (in Central Asia, Transcaucasia, etc.) there were three to four times as many primary-school pupils as before the Revolution. Peoples whose language had never had a written form were given an alphabet. Primers and other schoolbooks were written in the languages of the peoples of the Soviet Union. In 1928 books were published in seventy national languages, and by 1934, the number of languages in print was 104.

Nevertheless, Krupskaya saw literacy training as only the beginning of the adult education process. She called for the elimination of semi-literacy, the continuation of learning through self-education, and the constant enrichment through life of both general and specialized knowledge. In the many articles she devoted to self-education, Krupskaya set out the content, form and methods or organization of the wide range of assistance on offer to those who were learning independently.

She expressed her opinion that such work ought to enlist the services of all state enterprises and institutes, community organizations, educational establishments, the mass media, scientists and those who worked in culture. On Krupskaya’s initiative a network of evening and in-service general secondary schools for adults was set up, where the level of instruction took account of the age and experience of students.

The scientific foundations of teaching methods and content

An important axis of N.K. Krupskaya’s work after the October Revolution was her contribution to the radical alteration of the content of education, development of new curricula and teaching methods for school, and the writing of new textbooks. ‘It is now necessary to give new content to teaching, to link school as closely as possible with life, to bring it closer to the population, and to organize genuine communist education of children’ (Vol. 1, p. 596-7).

The knowledge imparted to children at school must prepare them for creative activity, work, and the construction of socialist society. Krupskaya wrote, ‘We must not content ourselves with teaching reading, writing and arithmetic; pupils must learn the rudiments of the sciences, without which it becomes impossible to make a conscious, active contribution to life’. She saw natural science as a fundamental discipline that afforded a materialistic understanding of natural phenomena and the ability to use the forces of nature wisely; another basic discipline was social science, which explained class relations and the ways in which society developed. Krupskaya believed that schools for the masses should provide a sufficiently high theoretical level of knowledge; and in 1918 she expressed the principal task of Soviet education as follows: ‘we must take from science all that is important, substantial, vital—we must take it and immediately apply it to life, put it into circulation’.

Surrounding herself with the best forces in education, Krupskaya in effect led the development of the new contents of school education that were based on the achievements of science. She carefully studied the curricula developed and reviewed new textbooks, and strove to establish closer thematic links between them. In this connection she wrote, ‘The workload should 4

not overwhelm pupils and should leave them sufficient time for independent work, rational organization of collective life in school, […] physical work and active involvement in daily life’

(Vol. 3, p. 44).

The development of cognitive activity in students is another important subject in Krupskaya’s educational legacy. This should be not a formalized system but ‘a fortifying understanding of things, of their very essence, which facilitates the comprehension of the development, interrelations and manifestations of phenomena—a dialectical system’ (Vol. 3, p.

544). In this way she sought to ensure that the knowledge imparted by general education would help students to form a scientific view of the world.

Krupskaya’s work on teaching methods had a considerable effect on the development of methodology and its use in Soviet schools. She considered that the principal objectives of teaching methods were to induce pupils to think independently and act collectively in an organized fashion, aware of the effect of their actions, and to develop a high degree of initiative. The teacher should also show children how to acquire knowledge by themselves, to work with books and newspapers, to express their thoughts in speech and in writing, and to form correct conclusions and generalizations. Since the old schools had not attached due significance to the development of scientific teaching methods, Krupskaya worked hard at developing a completely new approach to teaching methods and at enhancing their place in socialist schooling. She wrote that the teaching method should be organically connected with the essence of the subject being taught and with the history of the subject’s development. In an article entitled ‘Notes on Methods’ she demonstrates the special features of teaching methods deriving from the context of such disciplines as mathematics, nature science and social science.

According to Krupskaya, further criteria for proper determination of teaching methods were: consideration of the child’s personality, age and psychology; the organization of independent observations and practical activity; development of the ability to distinguish the particular and specific from the general and generic; teaching students to express and defend their own thoughts; fostering an inquisitive approach to the world outside school hours; inculcation of skills for work, research, etc.

Krupskaya was sure that well-devised methods for the organization of teaching would help obviate formalism and regimentation, passivity and insecurity in children. For this reason she believed that a teacher’s mastery of methods was a combination of creativity and craftsmanship, and she made high demands on teacher training. She maintained that Soviet teachers should not only know their subject well, but also have a perfect command of teaching methods and know the ways and means of teaching effectively.

Polytechnic education

It was Krupskaya who elaborated the idea of polytechnic education from the Marxism-Leninist classics, developing its pedagogical basis and putting it into practice in schools. She wrote that the universal implementation of the polytechnic system in education was to ‘present students with the basics of modern engineering, which all its diverse branches have in common’ (Vol. 10, p. 333).

Modern engineering was to be studied in all its aspects, that is, ‘in connection with general scientific data on the mastery of the forces of nature’, and also ‘with the organization of labour and the life of society’.

Study of the bases of production can take on a truly polytechnical character only when the theoretical leaning of the students is closely linked with their practical participation in productive work. ‘Such a combination’, Krupskaya observed, ‘will help the rising generation to comprehend the economy as a whole, without which it is impossible to become a genuine builder of socialism’.

Krupskaya did not consider the polytechnic system to be a separate subject with an independent curriculum, specialized teacher and textbook. The application of the polytechnical 5

principle was not to be confined to the school, the primitive school laboratories of those times, verbal explanations, excursions and meetings with leading workers. It was meant to be a component of general education above all—not vocational training. Krupskaya wrote,

‘Polytechnical education should be linked with mathematics, and with natural science, and with social science (Vol. 10, p. 333).

The difference between polytechnical and vocational schools is that the former’s centre of gravity is in the comprehension of the processes of labour, in development of an ability to combine theory with practice, to understand the interdependency of certain phenomena, whereas in vocational school the centre of gravity is the acquisition by pupils of working skills. [Vol. 4, p. 197.]

Krupskaya notes, however, that it would be wrong to conclude that the polytechnic system is simply a matter of acquiring an aggregate of knowledge and skill, of number of crafts, or merely the study of modern engineering. The polytechnic is a whole system that studies the bases of production in their various forms, states of development and manifestations.

Making schools polytechnic in this way allows the outlook of the rising generation to be broadened considerably, helps students to assimilate the ways in which the process of production tends to develop, and in this way enables them to become fully developed persons: the pupils do not limit themselves to the acquisition of particular skills for work, but assimilate the technical, technological and organizational bases of production, adapting easily to any innovation and working creatively and with great efficiency. With such an approach school not only helps pupils to develop harmoniously but also ‘captivates them with the romance of modern engineering’ (Vol. 4, p. 195).

Combining instruction with productive work

While studying the patterns of development of capitalist production Marx and Engels looked into the monstrous exploitation of child and adolescent labour. ‘Notwithstanding the horror of capitalist exploitation of child labour and the destruction of the old family institutions, Marx regarded the involvement of children and adolescents (as well as women) in production as a progressive phenomenon which would contribute to the establishment of higher forms of family life and serve to develop the human character’ (Vol. I, p. 310). This would of course involve only work that was within the powers of children and adolescents.

In a number of speeches and articles Krupskaya refers to Marx’s observation that the combination of instruction with productive and manageable work early in life is a powerful means of restructuring modern society and fostering the harmonious development of students. Krupskaya gives these ideas specific content, shows how they can be implemented, and analyses the first attempts at doing so.

In the early days of the Soviet regime not all schools had the wherewithal to organize productive work. Krupskaya explained that it was not necessary for the work of children to take place within the school. In those days children began their working life alongside adults early, especially in the countryside. That was real work and it had to be taken as the starting point and combined with instruction.

Later, when workshops had been set up in many schools, Krupskaya recommended that the work of schoolchildren should be of a productive nature, and the workshops were linked up with local industry.

Krupskaya considered that implementation of the polytechnic system, which provided a good awareness of the scientific bases of production, and of labour abilities and skills, was not in itself enough to solve all the problems connected with the preparation of active workers. People should love their work; also, they should have a conscious inner will to work, a deep understanding of the significance of their contribution to the common weal and a sense of responsibility for the 6

work entrusted to them. If these qualities are to develop, then the scientifically organized work of children and adolescents must contain some new, unknown element. Such work is fascinating to children; it gives a creative character to their work and prepares them for the working life ahead.

Krupskaya writes, ‘The work must be interesting and manageable and, at the same time, it must be creative and not merely mechanical work’ (Vol. 4, p. 247). The work must always be able to educate and raise the student to a higher level of development.

Another important aspect of labour education for Krupskaya was the inculcation of a sense of comradely mutual assistance and collective responsibility for the work done. To this end she advised those responsible ‘to consider to what extent the work imparted the skills of collective labour: an ability to set the principal aims, to get a measure of the work, plan it, and divide it in such a way as to ensure that each was allotted the most appropriate task within his or her powers; the ability to come to the assistance of comrades in their work, a capacity for evaluation of the work of each person in the productive process and of the results and effectiveness of the work’ (Vol. 10, p.

507).

Krupskaya saw such organization of collective work as one of the most important means of effecting the communist education of the rising generation.

Properly established polytechnic, and labour education and upbringing in conjunction with the whole range of educational and extracurricular activities contribute to the accomplishment of a further important task in society. They are the basis on which students, while still in the process of general education, freely decide their future place in society, making a fully conscious choice of vocation in accordance with their abilities.

A comprehensive approach to educational problems

Krupskaya believed the principal purpose of school education to be that of imparting to children and adolescents a scientific view of the world, communist morality and commitment to civic activity. That aim enabled her to ask and answer educational questions in a comprehensive way, not confined to interactions within teaching, but ranging much wider, with more substance and foundation. She saw great education potential in the links between school and life, in students’

participation in socially useful work, children’s self-management, and a wide range of extracurricular activity. Sharing her thoughts with Maxim Gorky, Krupskaya said: The construction of socialism does not mean only the building of huge factories and grain mills: such things are necessary, but not in themselves sufficient for the construction of socialism. People must grow in mind and heart [Vol.

II, p. 451].

Krupskaya considered children’s self-organization and self-management to be important means of character formation. In a country where the working masses had taken power into their own hands, school ‘self-management should endow students with the ability to pool resources and work together to solve the problems that arise in life’ (Vol. 3, p. 203-4).

She said that self-management in schools should aim to develop the activity of each child in study, work and socially useful tasks, in order to involve all pupils and offer them equal rights and opportunities, as well as equal obligations.

In the early years of the Soviet regime many teachers who had not yet achieved a sufficient grasp of the radical difference between the new type of school and the old, imagined that children’s self-management was a matter for the pupils alone. For this reason they keep their distance, leaving the children to their own devices and trusting in the pupils’ natural talent for self-management.

They did not understand that ‘one of the most important functions of self-management in schools must be the imparting to children of organizational skills’ (Vol. 3, p. 56) which they do not yet have. Krupskaya saw the teacher’s basic task as that of helping children to organize themselves, 7

suggesting to them in a comradely way how best to go about a given task, recommending how to ask the right questions and how to answer them, without under any circumstances doing all these things for them. The children themselves should discuss the questions collectively, take decisions and act upon them. In this way they develop a sense of responsibility for the work assigned to them, learn how to organize, and become more self-disciplined and capable of self-appraisal.

Krupskaya carefully studied and summarized all new information arising from extracurricular activity and worked out the pedagogical bases of the content, form and methods of organization of children’s free time. She considered organization of children’s technical creativity, and the study of nature, history, art and literature to be the main areas of extra-curricular activity.

Krupskaya was directly involved in the setting up of young naturalists’ and technicians’ stations, centres for excursions and tours, Pioneers’ and schoolchildren’s palaces and homes, children’s clubs, libraries and theatres, school museums, sports centres, playing fields, etc. Study groups and various types of creative association became the main channels through which children organized their own creative activities in such institutions, and they produced many distinguished scientists, civil engineers, natural scientists, managers of major enterprises, and exponents of culture. For Krupskaya, extra-curricular activity represented a most important means of broadening the polytechnic horizons of children and helping them to make a free and conscious choice of their future vocation. The name of N.K. Krupskaya is associated with the founding of the Pioneer and Komsomol organizations, and with their activities over many years. She saw the principal task of the Komsomol and the Pioneers as that of bringing up children in the spirit of communism, with a conscientious attitude to study and work.

Under socialism, the role of the family and the community in the upbringing of children is considerably enhanced. In contrast to earlier times, as Krupskaya remarked, under socialism the parents’ role is ever more closely bound up with the community’s educational activities. It was her view that the policy of encouraging parents to take an active part in the running of pre-school establishments, schools and extramural institutions, the propagation of educational information among parents, conversations and consultations with teachers and tutors on a one-to-one basis, and home visits, all would give a purposefulness to education and mutual interest to those involved in it.

She emphasized that schools and families would always have to secure the participation of industrial collectives, organizations, institutions and societies. Krupskaya insisted constantly that society become more education-conscious: the educational knowledge of parents and of the population at large had to be increased.

Conclusion

Krupskaya’s ideas on polytechnic and labour education, on the harmonious development of the personality and self-management in schools, on close links between school and daily life, the family and the community, on the people’s teacher, together with her critical survey of the classics of educational science at home and abroad, are a treasure in the heritage of Soviet educational science.

Workers in the Soviet Union hold her name in high esteem as a daughter of the Soviet people who dedicated her life to the struggle for the victory of socialism and the flourishing of Soviet culture. Many schools, scientific and cultural institutions and streets bear her name; N.K.

Krupskaya academic prizes and a Nadezhda K. Krupskaya medal have been established; a monument in the centre of Moscow is dedicated to her.

The greatest Krupskaya memorial, however, is the application of her ideas, and their further development in the ‘Basic Guidelines for Reform in the General-Education and Vocational Schools’ and in higher education being carried out in the Soviet Union today.

8

Notes

- This article was originally published in Prospects, vol. 17, no. 2, 1987.

- Mihail S. Skatkin (Russian Federation). PhD. Professor of the educational sciences and member of the Academy of Pedagogical Sciences. Worked for many years at the Institute of Theoretical Education on subjects ranging from curriculum construction to the school of the future; a member of the institute’s scientific council. Author of several publications, including textbooks for students in teacher-training institutions, particularly, Teaching Methods for Secondary School: Some Problems of Modern Teaching (1982, in Russian).

- Georgij S. Tsov’janov (Russian Federation). Candidate in educational sciences at the Academy of Pedagogical Sciences.

- Quotations from the works of Nadezhda Konstantinova Krupskaya are taken from Pedagogiceskie socienenija v 11 tomah [Educational Works in Eleven Volumes], Moscow, APN RSFSR, 1957-63.

- Profiles of Comenius, Dewey, Pestalozzi, Rousseau, Ushinsky, and Tolstoy appear in this series of ‘100 Thinkers on Education.’

Works by N.K. Krupskaya

Prepared by Y.A. Alferov

Pedagogiceskie socinenija v 11 tomah [Educational Works in Eleven Volumes]. Moscow, APN-RSFSR, 1957-63.

Pedagogiceskie socinenija v sesti tomah [Educational Works in Six Volumes]. Moscow, 1978-80. These volumes include, among others: ‘Public Education for Children and Adolescents’; ‘Children’s Self-Management in School’; ‘Problems of Polytechnic Education’ (all in vol. 4); ‘On the Pre-School Education of Children’

(vol. 5).

O politehniceskom obrazovanii, trudovom vospitanii I obucenii. Sbornik [On Polytechnic Education, Labour Education and Instruction. Collected Works]. Moscow, 1982. 223 pages.

Scritti di pedagogia [Educational Works] Moscow, Progress, 1978. 311 pages.

On Labour-oriented Education and Instruction. (Preface by M.N. Skatkin.) Moscow, Progress, 1985. 165 pages.

(Published in Spanish as : La educacion laboral y la ensenanza. Moscow, Progress, 1986. 220 pages.

Works about N.K. Krupskaya

Prepared by Y.A. Alferov

Bibliograficeskij ukazatel’pedagogiceskogo nasledija N.K. Krupskoj [Bibliography of the Educational Legacy of N.K. Krupskaya]. Moscow, 1988.

Gon arovoj, N.K. (ed.). Pedagogiceskie vzglijady I dejatel’nost’ N.K. Krupskoj [Educational Views and Work of N.K. Krupskaya]. Moscow, 1969.

Klicakov, I.A . Domokraticeskie I gunanisti eskie idei v pedogogiceskom nasledii N.K. Krupskoj [Democratic and Humanistic Ideas in the Educational Legacy of N.K. Krupskaya]. Gorlovka, 1992.

Litvinov, S.A. N.K. Krupskaya: Zizn’, dejatel’nost’, pedagogiceskie idei [N.K. Krupskaya: Life, Work, and Educational Ideas]. Kiev, 1970.

N.K. Krupskaja i sovremennost’ [N.K. Krupskaya and the Present]. Vladimir, 1989.

Obitsckin, G.D., et al. Nadezhda Krupskaja: eine Bibliographie [Nadezhda Krupshaya: a Bibliography]. Berlin, Dietz, 1986.

Rudneva, E.I. Pedagogiceskaja sistema N.K. Krupskoj [The Education System of N.K. Krupskaya]. Moscow, 1968.

Teoreticeskoe nasledie N.K. Krupskoj i sovremennost’ [The Theoretical Heritage of N.K. Krupskaya and the Present].

Moscow, 1989.

Veli kina, V.M. N.K. Kruspkaja I sovremennaja skola [N.K. Krupskaya and Today’s School]. Moscow, 1989.

Copyright notice:

The following text was originally published in

Prospects: the quarterly review of comparative education

(Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education), vol. XXIV, no. 1/2, 1994, p. 49-60.

©UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, 2000

This document may be reproduced free of charge as long as acknowledgement is made of the source.