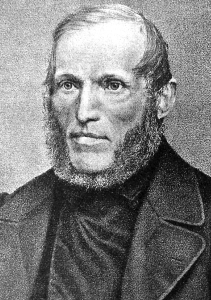

Kold, Christen, Mikkelsen (1816-70)

An article by Jens Bjerg

Around the middle of last century, Christen Mikkelsen Kold gave the Danish free school and the Danish folk high school the form they have today. Kold’s life and work must be seen against the background of N.F.S. Grundtvig’s revolutionary ideas about new ways of educating people and the need for general reforms of the Danish education system at the time.

Christen Kold was born at Thisted in north Jutland in 1816. At the age of 11 he was put to work as a shoemaker’s apprentice in his father’s shop. As he showed little or no aptitude for the trade, it was decided that he should become a teacher. Having served as a tutor on an estate, he was admitted to a teachers’ training college in 1834 and graduated two years later.

Even though he wrote practically nothing about pedagogical principles Kold’s influence was enormous. So much so that he is surrounded by an almost myth-like aura today. However, in order to understand the originality of Kold’s ideas, they must be placed in the broader context of Danish culture and society in the early nineteenth century.

The revivalist movement

The distinctive features of Kold’s pedagogy can be traced back to his conversion and revolt against the preachings of the established church. For ‘awakened’ souls like Kold the immaculate conception of Christ, his descent into Hell and ascension to Heaven were real events. Damnation and Hell were concrete and inevitable destinies for those who did not see the light in time. Baptism and Communion were actual meetings with God. Heaven was a real place, a safe haven for the awakened. In Kold’s view such matters could not, and should not, be reduced to symbolic representations of the struggle between good and evil, as the established church would have it.

Later in life Kold referred specifically to his awakening in 1834 as the source of his ideas about education:

Earlier, I thought God was a policeman, a strict schoolmaster, who watched over us and gave us a good box on the ear when we were bad. Now I realized that God loved both humanity and me, and I had this feeling that I too loved mankind – and to a lesser extent myself – and I felt joy because God loved me. I have never experienced anything like the life, the joy, the strength and power that suddenly arose in me. I was so happy about that discovery that I did not know which leg to stand on. I sought out my good friends in town and told them the wondrous news. I hardly knew what I was saying, but I managed to convey to them that God loved me and the whole of mankind despite our being sinners.6

The fact that his friends thought him out of his mind was to Kold further proof of the authenticity of his experience, the early Christians having been treated in the same way:

I saw how the power of the word could make hearts happy. It was the second time this realization dawned on me, the first being when my mother imbued me with that feeling. It soon became clear to me that God had given my words such power or put such words in my mouth that I could do the same. I made up my mind that very moment that this should be my business in life. I was not going to quit the teachers’ training college. I would endure it, but my main task in the world would be to make hearts happy with the message that, although we were sinners, God loved us through his son, Jesus Christ.

The two passages are characteristic of Kold’s style. He would use examples from his own life to encourage people or to enlighten them. Usually, it is the edifying tale about how to achieve one’s goals in life without failing in one’s obligations to oneself and to others.

In 1825 Grundtvig had started his crusade against the established church by maintaining that Christian dogma about the conception, death and resurrection of Christ were contrary to reason. The crucial point was a question of faith, not of reason. Christianity, in Grundtvig’s view, was incompatible with the kind of enlightened reasoning and rationality preached by the established church. Reason could never be the source of a Christian morality, just as faith could never be a derivative of biblical exegesis. The foundations of Christianity were the Apostles’ Creed, faith in the Holy Trinity and the renunciation of the Devil and all his works. A true Christian, Grundtvig claimed, need only follow these simple precepts to prove his sincerity. Sophisticated and hair-splitting biblical exegesis was not only superfluous, but harmful. Grundtvig’s writings had an immense influence on people’s view both of church and school. To some extent, the religious fundamentalists agreed with him, although they did not abandon the idea of the Scriptures as the basic source of inspiration for the church.

At the age of 19 Kold had been introduced to all of these issues by teachers in his college and by revival preachers who travelled round the country. The following year he graduated as a teacher, but had difficulty in finding employment as he refused as a matter of principle to use the obligatory textbook in religious instruction. He gained some support for his position from Grundtvigean clergymen, but in reality he was blacklisted and debarred from teaching in public schools for the rest of his life.

Grundtvig, Kold and the Danish school about 1830

Kold set about propagating his cause. Orally and in writing he argued against the use of compulsory textbooks and rote learning in Danish schools. Education in public schools was based on the Education Act of 1814, which did away with the widespread education of children in their homes, stipulating as it did that public schooling was compulsory – at least for the children of the populace. Till then parents had been free to use children to work on the farm, in a workshop or in trade as they saw fit, and they were equally free to give them the instruction that they thought necessary. Kold sympathized with the underlying principle of this state of affairs: his idea of a school was one that, above all, complied with parental wishes. A school should teach things to children that were in accordance with their parents’ Christian faith and particular way of life. So when for brief periods of time Kold managed to land a job as a teacher in a public school, he steadfastly refused to follow the regulations laid down by clergymen, who functioned as the official board of control. In Kold’s view, children were not to be taught to read and write until they were able fully to understand what they were reading or writing about. Instead, they were to be taught biblical history and history. Nor should they be confined to a classroom. The teacher should arrange outings and excursions and use these opportunities to give children relevant information. At the same time, children should be free to tell the teacher anything that crossed their minds. For Kold all education was centred round the act of narration: everybody has something to tell which is worth while listening to. Imaginative play with reality and the telling of stories are indispensable to the activity of learning, which is why children should be allowed to remain children for as long as possible and be given a free hand to fantasize and play.

An idea which immediately suggests itself is that Kold was familiar with the thinking of Pestalozzi. Even if Kold nowhere refers directly to him, it is a fact that Gerhard Peter Brammer, the principal of the teachers’ training college that Kold attended, was much influenced by Pestalozzi. In his ‘Lecture on the Centenary of Heinrich Pestalozzi, 12 January 1846’, Brammer said that in all his pedagogical work the image of Pestalozzi had constantly been present, sometimes as instruction, at other times as elevation and now and then as humiliation. It is true, Brammer continued, that the image of Pestalozzi was marked by deep shadows, but he would be remembered always for his love of children and his sympathy for the poor. For him teachers should not be ‘soulless censors’, but bearers of the ‘living word’. Education was a matter of oral presentation, and private schools were infinitely preferable to public schools. Incidentally, Pestalozzi was required reading in Danish teacher training colleges at the time.8

Such ideas stood in sharp contrast to the dominant enlightenment ideology of the Danish church and school. The clerical view was that rote learning was the central element in the education of a child and that the measure of successful education was how much pupils had learnt by heart.

Kold was an instinctive follower of Grundtvig in his crusade against the rationalist ideology of church and school, and from personal experience he was convinced that Grundtvig was right in stressing the importance of narration and dialogue in any educational process. The single most important element in Grundtvig’s falling out with church and school was the issue of whether faith should be grounded in the reading of books or based on personal experience. For Grundtvig it seemed obvious that if reading became the crucial factor, lay people and the populace at large would have to submit to the clergy and the professional classes, whose judgement was at best doubtful. This anti-authoritarian attitude appealed immensely to Kold.

In a broader context, Kold’s ideas, as they were articulated between 1835 and 1870, fell into a hiatus between an autocratic ancien régime and the beginnings of a bourgeois society that opened up vistas of social mobility and individual liberty. Kold’s ideas had an immediate appeal for many farmers and peasants, who were struggling to gain economic and, above all, political influence. Though numerically impressive, they were badly organized and had little political clout.

The main reason for the success of Kold’s ideas is to be found in the convergence of Grundtvig’s and his own ideas combined with a widespread animosity, especially in rural areas, towards the Establishment in all its forms.

The national awakening

In the spring of 1838 Kold took up a job as a private tutor in North Schleswig after he had once again been denied a teaching post at a public school. Partly as a result of his own and partly as a result of the efforts of the Reverend Ludvig Daniel Hass (1808-81), an supporter of Grundtvig, Kold became a potent symbol for the struggle between rote learning and Grundtvig’s ‘living word’, even though Kold himself never thought of himself as a fully committed Grundtvigean.

The following year, as a direct result of the growing tension between Denmark and Germany over the border between the two countries, Kold started a series of meetings with the declared intent of setting in motion a popular and national awakening. The main fare of each meeting was the retelling of Danish historical romances for young people fashioned in such a way as to make possible a worldly (national) awakening, in the same way as he himself as a young man had experienced a religious awakening. As far as the education of children was concerned, he was quite explicit about this mixture of secular and religious motives in so far as his aim was ‘to enlighten them and imbue them with such a desire, energy and vigour as to make them believe in the love of God and the happiness of Denmark, and to make them work for this end to the best of one’s modest abilities.

Kold was now convinced that children could learn anything if teaching took the form of narration instead of the reading of books. In his own work as a tutor he concentrated exclusively on oral narrative and gave up rote learning in all its forms. And, more importantly, he was now sure that his mission in life was to work as a teacher, both for children and adults. This was his destiny, inspired partly by Grundtvig and partly by his own religious awakening.

However, he was still kept out of the public schools. Frustrated and unhappy, Kold eventually accepted an offer from Hass in the autumn of 1841 to accompany him on a missionary trip to Turkey.

Hass and his family settled in Smyrna. Kold had expected to work together with the priest, but in this he was disappointed. His job was to wait on the family, which he did until he managed to set himself up as a bookbinder. He stayed in Turkey for five years. When he decided to return to Denmark, he sailed first from Smyrna to Trieste in Italy. There he bought a push-cart for his belongings and proceeded to walk on foot the 700 miles to Denmark. During his stay in Turkey he had managed to save up money which he was determined should be used to start his own free school.

The establishment of free schools and their pedagogy

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, pedagogical thinking was heavily influenced by the philosophy of the Enlightenment. Key figures were Rousseau, Basedow and Kant, who based a series of lectures on the education of children in 1776/77 on Basedow’s Elementarwerk, published two years earlier. According to Basedow, children were to be treated as children, not as small adults, and school work should be a matter of bringing out the best in young inquiring minds through play and imaginative exercises. The Danish Education Act of 1814 had been inspired by such ideas. However, the established church saw to it that a rigid framework of compulsory measures and regulations accompanied the Act, above all in the shape of rote learning and the learning of the catechism by heart. Another reason why the Act could not live up to its enlightened ideals was that the national finances were in disorder and teacher training was of mediocre quality.

To Kold the philosophy of the Enlightenment was a disastrous step backwards. He was convinced that in the long run it would lead to the dissolution of the Danish nation State, as it ignored the past and the specific cultural norms and common efforts and dreams that made up the national identity. The conflict with Germany over Schleswig-Holstein in 1848 and again in 1864 seemed to Kold a stroke of good fortune in that it brought about a national awakening and kindled the sense of a Danish national identity.

In the 1830s Grundtvig had consistently tried to work out plans for a new type of school, which resulted in the publication, in 1836, of the Danish Foursome, and, in 1838, of his School for Life and the Academy in Soer. His ideas were clearly spelt out: he wanted a new type of school and university for young people of all classes to take the place of the classical Latin schools and the university, which were the domains of a privileged elite.

Kold did not see things in the accepted way. His immediate concern was the establishment of schools for the children of ordinary people, especially in rural regions. The children of the poor would attend these schools from the age of 7 to the age of 14. Whether or not they retained their original social status afterwards was not of the slightest importance to Kold. The important thing was that, through the spoken word, these children would become enlightened and awakened in the same way as he himself had been. This was a far cry from the philosophical ideas that had inspired the Education Act of 1814 and his programme had little in common with Grundtvig’s School for Life and the Academy in Soer. The central point for Kold was the enlightenment—in a religious/national sense – of children. The main obstacle to the achievement of that goal, as he saw it, was the emphasis on rote learning in schools, and so he started to experiment.

In the morning I started right away by telling the children a piece of biblical history, which they loved to hear.

However, the problem was whether they would be able to remember it once they were called on to do so at their confirmation or at an exam. So for a fortnight I told them the story about Joseph, which to me seemed the best place to start. Then I set out to check whether the children could remember the story, and much to my surprise they were able to repeat it word for word the way they had heard it from me. Children have this strange ability that they can repeat things that they have heard word for word, and once one gets to know children, it is easy to understand why.

We adults cannot do the same thing because in admitting what we hear into our hearts, we cannot but refashion it a little bit according to our own heart before we pass it on. But when children admit something into their hearts, they pass it on in the very same form in which they have heard it. I reflected on this and saw that now we had found the method to teach all Danish children and the best means to recreate Denmark such as it once was.10

On November 1, 1849, Kold took up a job at Ryslinge in Funen as a private tutor in the household of the Reverend Vilhelm Birkedal (1809-92), a keen supporter of Grundtvig’s ideas. Most of his spare time was spent making plans for the private school he was determined to set up. Birkedal supported him actively and saw to it that he was given financial aid by people who for one reason or another were critical of public school education. Kold also applied for and obtained a State grant for his project.

On 1 November 1851, Kold’s school at Ryslinge started with ten students between 15 and 20 years of age. Kold and a friend, Anders Christian Poulsen Dal (1826-99), were to teach the young men for two winter terms, that is each year from 1 November until 1 April. Kold and Poulsen Dal lived under the same conditions as their students, ate the same food as they did and slept beside them at night in the loft above the classroom. Some ten years later, a Swedish visitor to Kold’s folk high school at Dalum described the man and his teaching in these terms: People had talked to me about the eccentricity of the man, but I wasn’t really sure what kind of a person I was going to meet. In front of me stood a middle-aged man with fine, clear-cut features dressed like a farmer in a homespun coat and with a little cap on his head. […] And then he started his lecture. The students were sitting in a circle around him like intimate friends, and he began to tell them how a mysterious force that would not leave him alone had driven him to carry out his plans. His mind had warned him in vain of the debts he would incur. His spirit had insisted with equal force: You must! The funds will be found as they are needed. And this had come to pass. […] He related all this in a simple and straightforward manner, without the least trace of pompousness and with frequent references to things and conditions that were familiar to his audience – all in order to give them confidence and courage in their efforts to reach for higher things. Again and again there were instructive examples from the Bible. One could feel and sense his conviction that he had received a special calling, and this conviction communicated itself to his apprentices. It was just a little bit overwrought. Be that as it may, it had none of the morbid exaggeration so characteristic of the truly self-absorbed. It was more like the spark from a holy flame found in all powerful characters who have contributed to the betterment of the world. Except for the strongly felt presence of Kold’s personality there is nothing in the school that makes it different from other Grundtvigean schools or folk high schools in general. There are the same relaxed teaching methods, the same lack of compulsory homework, self-instruction through the reading of first-rate authors, essay-writing and, finally, a fresh and vigorous song.11

Kold himself wanted his students to think of their experience in the following way: We are a group of young farm lads, who are staying for some months at the home of Christen Mikkelsen Kold, a farmer in Hjallelse. We lend him a helping hand in his work, we have conversations inside and outside, we listen to talks, we improve our writing, arithmetic and such things, and when those months are over, we go each his own way, resume our usual tasks and are the same plain farm lads as we were before.12

Kold insisted that a school ought to resemble the pupils’ home as much as possible in order that they might feel receptive and relaxed. The classroom, for instance, should look like an ordinary living room. This, however, did not imply that the bringing-up of children was in any way the responsibility of the school, let alone the State. Parents alone were responsible for the upbringing of their children, and the task of the free schools was to emulate the kind of education and training that used to take place at home before the Education Act of 1814. This became part of the official programme when, in the spring of 1852, Kold and Poulsen Dal set up the first free school for children in the small village of Dalby, at the same time as their high school for young men was moved from Ryslinge to Dalum.

The last and biggest school that Kold built was a high school at Dalum near Odense, which was opened on 1 November 1862 with an intake of fifty-eight students, all of them male. The following year eighteen young women were admitted to the school. Here Kold spent his last years.

In 1866 he married Ane Kirstine Jacobsen and became the father of two daughters. He died on 6 April 1870, aged 54.

From around 1850, when he set up his first school, until a few years before his death, Kold had constant economic problems. He received help from sympathizers, but it was only after he had settled at Dalum that he managed to repay all his debts as the schools became economically viable.

He also had altercations with principals of other emerging high schools, whose teaching methods differed from his ‘Christian, historical and poetic’ pedagogy. Kold’s aim was always to enlighten, encourage and awaken while the programmes of other schools were more in accordance with Grundtvig’s idea of enlightened instruction through the spoken word. Also, Kold’s overwhelming personality reduced his fellow teachers to little more than stand-ins, which was one reason why the high school at Dalum closed only a few years after his death.

Kold was a man of the people who remained loyal to his social origins. His ambition in life was to create a school of and for the children and youngsters of the lower classes. As it turned out, it attracted pupils mainly from better-off farming communities and never managed to gain any kind of foothold among the growing industrial workforce in the cities. That set the limits to Kold’s achievement. At the same time, it goes some way towards explaining the endurance and success of his ideas. The fact that the free schools and, at a later stage, the folk high schools managed to establish themselves as an integral part of, and yet as an alternative to, the established education system was to a large extent due to Kold’s personal efforts and zeal.

Kold’s pedagogical theory14

All pedagogical theory is based on a number of assumptions about human nature and the meaning of life. Many of Kold’s talks are attempts at making these assumptions explicit. In his view human beings were governed by two basic emotions: that of Christianity and that of the people or the nation. These emotions constitute the basic social make-up of any individual. Only through a simultaneous recognition of these emotions can the individual arrive at an understanding of ‘the true conditions of life’, as he put it. To Kold such an understanding was a precondition for the life of the individual and the survival of the people and the nation. The individual must have an awareness of its origins, its destiny in life and ultimate fate once its existence on earth comes to an end. Otherwise he/she will be unable to live a meaningful life and fulfil his/her destiny. The prerequisites, according to Kold, are Christianity and history. Christianity provides man with answers to such fundamental questions as the creation of the Universe, the fall of man and the road to salvation and, consequently, reveals the tasks that confront the individual and the community, the people and the nation that he or she is part of. History traces the long journey of the nation and the people, demonstrates how mistakes were made, rectified, and people and communities spurred on to new efforts. The philosophy of the Enlightenment in its Danish version was to Kold’s mind one of those mistakes that would lead to new insights and a change in national consciousness.

To Kold intelligence and professional knowledge were inferior to the power of the imagination and empathy – the ability to transcend the given and combine elements of reality in new ways. Imagination and empathy were the driving forces behind associative and combinatory processes. As such they were clearly distinct from what he called emotion, which was the source of existential choice and commitment to a cause. Imagination and empathy were primordial qualities; intelligence came later. The purpose of the human capacity for understanding was for man to perceive the ‘true conditions of life’. The crucial point in Kold’s view was that cognition of this sort could not be achieved by rational means. It was to be found in particular forms of narrative—biblical or historical—and could only be arrived at through an imaginative effort. Consequently, the source of cognition would have to be ‘the spoken word’—the oral narrative, the heartfelt conversation—and not denotative or rational types of discourse. The individual seeking the truth was by definition serious and enthusiastic—or as Kold himself put it ‘enlightened’—and enlightenment was a necessary precondition for a change of direction in people’s lives.

So biblical history, Nordic mythology and Danish history became core subjects in Kold’s schools and the mode of teaching was predominantly oral narration. Since a child has only a limited stock of experience to draw on, Kold argued, ‘it is the duty of the school to place it right in the middle of events by means of the powers of the imagination so that he can get a clear notion of the race he is part of and gather the experiences necessary for the continued life of the race.’15 This quotation is from the only pedagogical pamphlet Kold ever wrote. Incidentally, it was not published in his lifetime, but only in 1877. In the following paragraphs we shall take a closer look at this little treatise.

In Denmark there is a current debate over the aims and purposes of primary education.16

The present Act dates from 1975. It is based on a three-fold division of the school’s aims:

In co-operation with the home, the school should ensure that pupils are given the opportunity to acquire knowledge, skills, working methods and forms of expression that may contribute to the individual’s all-round development.

In all its activities, the school should seek to create such opportunities for experience and personal activity as will increase the pupil’s desire to learn, to exercise the imagination and train the ability to assess, appraise and reach independent judgements.

The school should prepare the pupils for active participation in a democratic society and a shared responsibility for the carrying out of common tasks. Instruction and everyday life in school must be based on intellectual and spiritual liberty and democracy.

In 1850 Kold reflected on the purposes of primary education and wrote:

It would be foolish of me to deny that a government may not have good reasons to want the population to be well-informed; any father would want the same for his own children; but not knowledge which is dead. Education, says professor Sibbern, is more than instruction [in dead knowledge] and goes on: How many people do we not see who are well-read, proficient and in possession of fine skills, but in whom these things do not appear as the basis of their existence. They have not become flesh of their flesh, blood of their blood. They possess them, but they have not acquired them. And more than both instruction [in knowledge] and education, is refinement of the spirit. One wants to see one’s children well-instructed; one wants more; one wants them to be educated; but ought one not to wish for even more? Ought one not to wish to see them moving along freely and sprightly in life with open minds and brimming with certain fundamental ideas and interests, which might infuse all that has been instilled into them by instruction and all that they have acquired through education, and make it bear on fine and healthy lives so that all will not stagnate in them?’

Drawing on Sibbern, Kold here defines primary education as a mixture of instruction, education and refinement of the spirit. The three concepts reappear in the present Primary Education Act although in a different order and under other names: the first paragraph talks about instruction, the second about the refinement of the spirit, and the third about education.

To Kold it seemed self-evident that there must be a dialectic between the three concepts.

The refinement of the spirit was the ultimate goal at the same time as it was the precondition for and most efficient means of bringing to fruition the processes of instruction and education. He was convinced that if he succeeded in awakening the spirit, instruction and education would follow of themselves. The awakening was both an end and a means in his pedagogical thinking, and the three processes of instruction, education and refinement of the spirit would ideally grow out of the same teaching method.

Kold’s reflections on children’s needs and abilities led him to conclude that, as far as instruction was concerned, ‘content must take priority over form, the inward over the outward.

One must have something to write about before one learns to write. One must have a desire for knowledge before one learns to read, in order not to take appearance for reality, the means for the end and the sign for the thing.’18 Another important principle was that children should not be taught skills and given knowledge until they themselves understood the reasons why and could see ‘the necessity of the information given to them, in that they can apply it immediately, be it for business or for pleasure.’19 Skills and instruction that could not be put to immediate use he called dead knowledge, ‘false and illusory opinions that have no bearing on people’s thoughts, let alone their lives.’20 Homework, exams, the catechizing and grilling of pupils in the classroom were necessary only in connection with the checking of dead knowledge, Kold said, which was why there was no need for them in his schools.

The widespread criticism of the public schools and their teaching methods resulted in a new Primary School Act in 1855. For the free schools the most important provision was the right for parents to decide for themselves the kind of instruction that they wanted for their children. The immediate result was a growing number of pupils in the free schools and more freedom for the teachers to practise the method of oral narration. Through the spoken word (Grundtvig wrote), ‘which is the natural way, formed and made available to us by the Creator, through the ear to the heart, in contrast to the artificial way of writing, children shall become aware of their own existence by hearing about their ancestors’ lives.’ At first they may not grasp the connection, but only find it amusing. Later they will be able to see more deeply.

To Grundtvig ‘the living word’ was a unity of something sensual and ethereal. As a grateful recipient of God’s love and mercy, he was more than willing to talk about sensuality. For Kold it was almost impossible because sexuality and the sensual touched on deep-seated fears in him. In Grundtvig’s view, love of the world was a precondition for a cognition of the love of God. Kold, on the other hand, had to suppress it to come to terms with God. Grundtvig made a sharp distinction between the human and the divine to prevent men from striving in vain to suppress their sensuality, whereas Kold was so obsessed by his love of Jesus that his own sensuality was a lifelong source of loathing and fascination to him. Kold was familiar with the works of Søren Kierkegaard, and it is pure Kierkegaard when he talks about the fear of a punishing God as the touchstone for all human actions or the importance of the choice if freedom is not to become a burden. Born and raised in widely different circumstances, Kold and Kierkegaard had nevertheless both of them experienced a religious awakening and both of them were haunted by the fear of damnation.

Grundtvig’s brand of Christianity was a different thing altogether.

The fundamental event in Grundtvig’s life was the realization that human existence could not, and should not, be regulated according to a Christian ideal, since the essence of Christianity was the Gospel and not a set of laws to be broken or obeyed. This was the point of departure for his attacks on the established church and the education system. He wanted to challenge all pious orthodoxies, classical education, the death, as he saw it, of a living culture. In the face of this, life could not but be right, life as we experience it, in ourselves, in people and in the march of history. It was for this purpose Grundtvig wanted to use the folk high schools. He wanted ordinary people to discover the same insights and reach the same conclusions as he had. ‘We need a People’s Enlightenment, an enlightenment of Life, to fight death in whatever form it takes: the authoritarian coercion, the snobbery for everything foreign, the contempt for all that is one’s own, all spiritual domination, the hopelessness […].’ To Grundtvig Christianity was one thing, humanity another.

God had created the world as a place for man to live in. Good works should be of use to people in this world. They were not to be understood as some kind of preparation for a life to come. It is in this light that Grundtvig’s ideas about education should be understood. The school should be of use to life on this earth. It should be a school ‘for life’, as he himself put it, not for eternity. Kold never understood Grundtvig’s approach to Christianity and, consequently, he never fully agreed with his views on education. The decisive moment in Kold’s life was the realization that ‘God loves humanity’ and that changed his life. From then on his main preoccupation was the struggle for salvation and eternal life, not just for himself but on behalf of all men. This was why the 8notion of ‘awakening’—in a religious sense—became of crucial importance in his schools. It is true that Kold and Grundtvig to some extent used the same vocabulary—‘enlightenment’ and ‘encouragement’—to describe what they were trying to accomplish. But their ultimate goals and visions were, if not incompatible, at least very dissimilar, something which is still noticeable in the different kinds of folk high schools found today.23

It was Kold who gave the free schools and the high schools the form that they have today.

Students spend five months at a school in continuous contact with the principal and the teachers, eating at the same table, sharing the same amenities, etc. ‘Kold made it all very down-to-earth, having realized that one had to be oneself and that things had to be plain in order to be true. He founded his high school on a discovery that gave him the courage to be himself: the discovery of God’s love.’24 In different circumstances and on the basis of a different philosophical stance, other pedagogical thinkers have reached almost the same conclusions as Kold. For instance, John Dewey’s ideas about education have many affinities with Kold’s thinking, and even today they seem to have a genuine appeal.25

The folk high school today

Today there are about 200 free schools and 100 folk high schools in Denmark. They represent the heritage of Grundtvig and Kold, especially in the question of parents’ right to decide the kind of instruction that they want for their children. In that respect, both Grundtvig and Kold have left their imprint on the public system of education. At the same time the teaching methods and programmes of the free schools and folk high schools have changed—some would say that they have been diluted—so that today there is a broad range of different approaches and subjects on offer.

The high school today is many different things, perhaps as many and as different as there are high schools. They come in all shapes and forms, from the most boringly reactionary—constantly harping about genuine peasants and the good old days—to the opposite extreme, the opportunistic, trendy school whose main ambition seems to be to attract more students. And in the middle of all this there are still schools with a sober and responsible approach to problems and issues from the past and the present. There are schools where nothing seems to have changed since the time of the popular enlightenment in the nineteenth century, and schools that under the impression of the present confusion have discarded Danish poetry and Danish history and seem set on students’ creativity as the only patent medicine. Classes in ceramics, drawing, embroidery—with a total disregard for quality—have taken on a religious function. But there are also schools, whose point of departure is today’s living conditions and the problems that we face, which do their best to open up young people’s eyes by confronting them with more genuine experiences and broader philosophies of life than can be found in the products of the endlessly triumphant entertainment industry.

Be that as it may, Danish scepticism of any form of spiritual and political authority is closely connected with the ideas of Denmark and a particular Danish national identity that developed from the 1840s to the 1940s. The source of that scepticism is to be found in the ideas of Kold and Grundtvig. The latest evidence of the tenacity of that tradition came in 1992 with the Danish referendum and the refusal by the population to ratify the Maastricht Treaty of the European Community.

Notes

- Jens Bierg (Denmark). Senior professor of educational psychology at Roskilde University Centre. Previously worked as a school-teacher, school psychologist, and professor at a teacher-training college. His research and published works have concentrated on educational development and pedagogical theory, particularly regarding educational practice in Denmark. He is currently undertaking research on European education systems and curricular studies.

- The author wishes to express his gratitude to Professor Gunhild Nissen of Roskilde University Centre for numerous useful suggestions, and to Henning Silberbrandt, lecturer at Roskilde University Centre, for the translation of this article into English.

- A profile of N.F.S. Grundtvig also appears in this series of ‘100 Thinkers on Education.’

- Except for a few brief texts, Kold only wrote one treatise, Om Børneskolen (1850) [On the Children’s School], published posthumously in 1877.

- In 1866 Kold gave a lecture at a two-day meeting in Copenhagen. His manuscript is lost, but the lecture was later published on the basis of a short-hand account. It is one of the most important sources for an understanding of his life and work. Grundtvig introduced Kold to the audience and said among other things: ‘And so I have asked Kold, the main inspiration of the popular enlightenment in Funen, to be so good as to tell us how he originally came to embrace his fruitful career and in what light he regards the whole issue of education, both the children’s school and the school for adults. And I have only one further remark to make, one that I usually never address to any speaker, which is that I hope that he won’t be too brief. This man has remained silent for so long that he probably has a good deal to tell us, and I believe that we have all the time in the world to listen to him.’

- Klaus Berntsen (ed.), Blade til mindekransen over højskoleforstander Kristen Kold [Leaves in the Memorial Wreath for High School Principal Kristen Kold], 2 ed., Odense, 1913, p. 11.

- Ibid., p. 12-13.

- Johannes Pedersen, Fra friskolens og bondehøjskolens første tid [From the First Days of the Free School and the Folk High School], Copenhagen, 1961, p. 23.

- Berntsen, op. cit., p. 14-15.

- Berntsen, op. cit., p. 16.

- Berntsen, op. cit., p. 62-64.

- Niels Højlund, Folkehøjskolen i Danmark [The Folk High School in Denmark], Copenhagen, 1983, p. 29.

- There are at least two accounts of Kold’s life and work in English: Thomas Rørdam, The Danish Folk High Schools, Copenhagen, 1965, p. 58-64; and Steven M. Borish, The Land of the Living. The Danish Folk High Schools and Denmark’s Non-Violent Path to Modernization, Nevada, 1991, p. 186-92.

- For the following text, I am indebted to Carl Aage Larsen, Kolds pædagogiske teori. In: Johannes Hagemann, et al., Christen Kold 1. Pædagogik [Christen Kold 1. Pedagogy], Copenhagen, 1967, p. 49-61.

- Johannes Hagemann and Harald Sørensen (eds.), Christen Kold 2. Udvalgte tekster [Christen Kold 2. Selected Writings], Copenhagen, 1967, p. 34.

- Jens Bjerg, ‘Provincial Reflections on the Danish Educational System’. Compare, vol. 21, 1991, p. 165-78.

- Hagemann and Sørensen, op. cit., p. 63. F.C. Sibbern (1785-1872) was professor of philosophy at the University of Copenhagen from 1813 to 1870. He was inspired by the German romantics’ rejection of the philosophy of the Enlightenment, especially by Fichte, Schiller and Schleiermacher.

- Hagemann and Sørensen, op. cit., p. 43.

- Hagemann and Sørensen, op. cit., p. 51.

- Hagemann and Sørensen, op. cit., p. 64.

- Hanne Engberg, Historien om Kold [The Story about Kold], Copenhagen, 1985, p. 329-30.

- Kaj Thaning, Grundtvig og Kold [Grundtvig and Kold]. In: Johannes Rosendahl (ed.), Højskolen til debat [The Debate on the Folk High School], Copenhagen, 1961, p. 80-82.

- Ibid., p. 85-86.

- Ibid. p. 92.

- Cf. the renewed interest in Dewey’s ideas, as in Richard Rorty’s lecture at the seventy-fifth annual meeting of the American Association of Colleges, 5 January 1989, ‘Uddannelse, socialisation og individuation’ [Education, Socialization and Individuation], Kritik 95, Copenhagen, 1991, p. 88-99.

- Bjerg, op. cit.

- Ole Wivel, Højskolens nederlag [The Defeat of the Folk High School]. In: Johannes Rosendahl (ed.), Højskolen til debat [The Debate on the Folk High School], Copenhagen, 1961, p. 151.

Writings by Christen Kold

Kold, Christen. ‘Skjærbæk Fattighus’ [The Poorhouse at Skjærbæk]. Dannevirke, no. 37, 5 February 1840.

——. ‘Spørgsmål til en Sagkyndig’ [Questions to an Expert]. Dannevirke, no. 43, 26 February 1840.

——. ‘Et Par Ord til Jyden i Sjælland’ [Some Words to the Jutlander in Zealand]. Dannevirke, no. 59, 22 April 1840.

——. Rejsen til Smyrna [The Journey to Smyrna]. Copenhagen, 1979. (Christen Kold’s diaries 1842-47.)

——. Om Børneskolen [On the Children’s School]. Copenhagen, 1877. (Posthumously published treatise.)

——. Historien om den lille Mis [The Story about the Little Cat]. In: Læsebog med Billeder for Småbørn [Illustrated Reader for Small Children]. Copenhagen, 1865.

10

——. Tale ved ‘Det kirkelige Vennemøde’ 10.-11. september 1866 i København [Speech at the Annual Congregational Meeting in Copenhagen, 10-11 September 1866]. Køster, K. (ed.), Copenhagen, 1866.

——. Breve 1849-1870 [Letters 1849-1870]. In: Skovmand, R. (ed.) Højskolens ungdomstid i breve [The Beginnings of the Folk High School in Letters]. Vol. 2, Copenhagen, 1960, p. 167-246.

A number of these texts can be found in: Hagemann, J.; Sørensen, H. (eds.), Christen Kold. Udvalgte tekster

[Christen Kold. Selected Writings], Copenhagen, 1967.

Writings about Christen Kold

Berker, Peter. Christen Kolds Volkhochschule. Ein Studie zur Erwachsenenbildung im Dänemark des 19.

Jahrhunderts [Christen Kold’s Folk High School. A Study of Adult Education in Nineteenth Century Denmark]. Münster, 1984.

Borisch, Steven M. The Land of the Living. The Danish Folk High Schools and Denmark’s Non-Violent Path to Modernization, Nevada, 1991, p. 186-92.

Goodhope, Nanna. Christen Kold. The Little Schoolmaster Who Helped Revive a Nation. Blair, NE, 1956.

Röhrig, Paul. ‘Impressionen und Reflexionen aus dem Mutterland der Volkhochschule’ [Impressions and Reflections from the Motherland of the Folk High School]. Neue Sammlung, 19. Jahrgang, Berlin, 1979, p. 457-70.

Rørdam, Thomas. The Danish Folk High Schools. Copenhagen, 1965, p. 58-64.

Simon, Erica. Réveil national et culture populaire en Scandinavie. Paris; Uppsala, 1960, p. 545-62. (Doctoral Thesis) Wartenweiler-Haffter, Fritz. Aus der Werdezeit der dänischen Volkhochshule. Das Lebensbild ihres Begründers Christen Mikkelsen Kold [An Account of the Danish Folk High School. The Life of its Founder: Christen Mikkelsen Kold]. Erlenbach-Zürich, 1921. Second edition: Ein Sokrates in dänischen Kleidern. Christen Mikkelsen Kold und die erste Volkhochschule [A Socrates in Danish Costume. Christen Mikkelsen Kold and the First Folk High School]. Erlenbach-Zürich, 1929.

Copyright notice

The following text was originally published in Prospects: the quarterly review of comparative education(Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education), vol. XXIV, no. 1/2, 1994, p. 21-35.

Reproduced with permission. Read the PDF version of the article here.