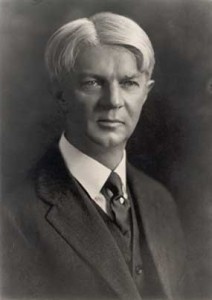

Kilpatrick, William Heard (1871–1965)

In the context of American education, William Heard Kilpatrick may be best known as a colleague of, and collaborator with, John Dewey, with whom he worked at Teachers College, Columbia University. Kilpatrick’s development and advocacy of ‘the project method’ is another accomplishment for which he is widely recognized. Yet the ideas, life and commitments of William Heard Kilpatrick go well beyond these relatively cursory understandings. In this essay, I describe and analyze some of the central features of Kilpatrick’s ideas and activities, while trying to develop a more complete picture of this important figure in the history of progressive education.

William Heard Kilpatrick was born on 20 November 1871, the first child of the Reverend Dr. James Hines Kilpatrick and his second wife, Edna Perrin Heard; they were married on 20 December 1870. Before that marriage, Reverend Kilpatrick, a widower, cared for the three sons and two daughters who had been born to him and his first wife. The elder Kilpatrick had moved to White Plains, Georgia, in 1853, after graduating from Mercer University, with the express purpose of teaching in school. After teaching one year, however, he became pastor of the White Plains Baptist Church, a position in which he continued until his death in 1908. More than simply an influential member of the clergy, the Reverend Kilpatrick was a central figure in the political, civic and legal activities of this small agricultural town. Indeed, he is even said to have ‘pulled teeth for anyone who came to his home’—a skill he had developed as the owner of a 1,600 acre plantation that included at least thirty slaves, an inheritance from his father.3 His religious convictions, as well as his personal and temperamental attributes, were to influence William strongly, and even, in certain ways, to permanently shape his character.

Kilpatrick’s father was stern, meticulous, serious-minded and essentially without humour. The Reverend Kilpatrick instilled in his son a commitment to detailed record keeping that would stay with him throughout his life. William kept a daily diary that in 1951 numbered some forty-five volumes, and wrote numerous letters to his family and friends. He also acquired from his father a penchant for clear, meticulous, well-developed thinking and the habits of hard, sustained work. As a result, William was widely known later in life for spending more time than most academics on his work activities; he often felt the pangs of guilt associated with commitments to teaching and scholarly investigations that took him away from his wife and children. He was also known, even as a young man, for wanting to become successful and a leader of some prominence. William also learned first from his father to speak out against inequities, and to express unequivocally even unpopular ideas about which he felt strongly.

William’s mother provided a counterbalance of sorts to the stern, humourless demeanor of his father. ‘Heard’ (the name which she lovingly used for her first son) learned from his mother the value of a sense of belonging, while becoming self-secure and self- confident. Of his mother Kilpatrick said, ‘she helped me early to learn not to be selfish, that I must give to others their just due; thus helping me early in life to balance the personal demands that might have been selfish against the rights and the demands of the other people.’ The relationship between William and his mother was apparently one that also helped fundamentally shape his dispositions and character—and even his teaching. He repeatedly attributed whatever success he had in teaching ‘to the fact that [his mother] inculcated in him a “fine sensitivity” to people—not to hurt anyone no matter how lowly.’ It may well be the case that Kilpatrick’s close, advocacy-oriented relationship with his students, discussed below, was prompted initially by that ‘fine sensitivity’ he saw in his mother.

William Heard Kilpatrick’s first venture into higher education took place in 1888 when he enrolled in courses at his father’s Alma Mater—Mercer University in Macon, Georgia. His experiences there, however, were less inspirational than they apparently had been for the Reverend Kilpatrick. Even as he began his junior year, William was without strong professional ambition and, in a larger sense, lacked a direction for his life. While he excelled first in ancient languages and then in mathematics, he had no firm sense of who he might become, having decided, like his brothers, not to pursue theological studies and become a member of the clergy. During his junior year, however, Kilpatrick stumbled upon a book that would have a long-lasting impact on his personal and professional life. Given the ideological contours of the strict religious household in which he had grown up, Kilpatrick had heard only that The origin of species was to be despised—a book which only wicked non-believers would take to heart.6 Yet Kilpatrick’s curiosity led him finally to borrow the book from a Mercer library. It proved to be a text that would shape in no small measure his general philosophy of education, and his own orientation to teaching. Concerning his initial reading of this work, Kilpatrick said,

The more I read it the more I believed it and in the end I accepted it fully. This meant a complete reorganization, a complete rejection of my previous religious training and philosophy. By accepting Darwin’s Origin of species, I rejected the whole concept of the immortal soul; of life beyond death, of the whole dogma of religious ritual connected with the worship of God.

Clearly, his exposure to the ideas in The origin of species was a monumental event in the young Kilpatrick’s life. He understood well the repercussions his changed orientation would have on his relationship with his parents, especially his father. Yet there was an important sense in which William’s moral convictions would continue in spite of his rejection of the religious creed that had been a part of his childhood. Foreshadowing his future commitments and activities, Kilpatrick noted that his denunciation of religion ‘did not change in any way my moral outlook. I now had no theology, by my social and my moral life continued in exactly the same way.’

After graduating from Mercer, Kilpatrick borrowed $500 from one of his brothers so that he might pursue graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University—an event that, like the reading of The origin of species, was to change the course of his thinking, and his life. Of his initial experiences at Johns Hopkins, Kilpatrick was to later say,

Even by breathing the air I could feel that great things were going on. I have never been so deeply stirred, so emotionally moved before or since. I had the feeling that here was the intellectual center of America. And I was eager to join this exciting new world; I too wanted to merge myself in this avid pursuit of truth. […] This institution had the power to influence a youth of twenty beyond anything now known in America.

It was Kilpatrick’s discovery of the domain of modern, evolutionary science, and his attraction to open-ended intellectual inquiry at Johns Hopkins, that led him to reject the religious orientation he had acquired in White Plains. These educational experiences led him to embrace the ideas and outlook of modern science and to become committed to the pursuit of secular truth. Later studies in philosophy at Johns Hopkins would reawaken his interest in religious ideas. Yet that interest re-emerged as part of his larger search for understanding and clarity that philosophical analysis might provide, and not as some commitment to particular religious dogmas or practices of the sort that had shaped his childhood. Kilpatrick’s fascination with science and inquiry helped provide that direction for his life that had been absent during his undergraduate days at Mercer. They also provided the impetus for many of his educational ideas, as he developed a philosophy of education that went beyond the individualism and the pseudo-scientific technicism of educators like John Franklin Bobbitt, Edward L. Thorndike, W.W. Charters, David Snedden, and others.

After completing one year of graduate work at Johns Hopkins, Kilpatrick returned to rural Georgia to accept a position as an algebra and geometry teacher, as well as co-principal of the Blakely elementary and high school. Since he had taken no courses in pedagogy as a part of his previous education, Kilpatrick was required to attend a summer normal school session at Rock, Georgia. One of the events in which Kilpatrick took part at the summer institute that was to affect his own thinking in significant ways was a lecture on the educational ideas of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi. This was perhaps his first inkling that a key to valuable education was the provision of meaningful, interesting experiences for students in which they could truly develop responsibility. Such an orientation rejected the popular view that the key to learning lay in mastery of remote knowledge from a book, and in its connection to discrete and disconnected lessons, recitations and examinations. Within this dominant view, genuine understanding was less than essential, and perhaps even a hindrance to that ‘toeing the line’ rigidity that would ensure scholastic success. Instead, Kilpatrick saw the need to get students involved in things that were meaningful to them, and became committed to devising activities that would build on students’ interests. Asked decades later about which ideas he was developing that first year of his teaching life that were to remain vital, Kilpatrick replied, ‘it was trusting the child, getting him in on what was happening. I wanted each child to feel that I was trying to help him. […] I wanted no division: the teacher on one side, the children on the other.’ Kilpatrick saw, during his early teaching experiences in Georgia, the importance of identifying with, and caring for, his students. Perhaps in part because of the nurturing relationship he had enjoyed with his mother, he could in later years remember virtually each of his former students, and enjoyed a fatherly relationship with many of them late into life. The provision of meaningful experiences for students that were connected to their intrinsic interests was more than a ploy to get students to pay attention or to complete assignments. It was rather the expression of a deep-seated commitment to, and respect for, his students as autonomous, self-directed people.

Another early influence on Kilpatrick’s educational thinking was Francis Parker, who had studied the writings of Pestalozzi, Herbart and Froebel at the University of Berlin. Kilpatrick attended a lecture by Parker in 1892, and came to regard him as the first American progressive educator, as well as a forerunner of John Dewey. As Principal of the Cook County Normal School, Parker was able to help others recognize the value of a sense of experience in education—an emphasis that was continuous with Kilpatrick’s commitment to providing meaningful experience for his students. Of his influence, Kilpatrick has said:

Francis Parker was the greatest man we had to introduce better practices into the country’s schools. I would now say that he took Pestalozzi’s ideas and improved and enriched them and carried them forward. He preceded Dewey, but Dewey came along with a much finer theory, a much better worked-out theory.

In spite of his clear devotion to teaching and to his students, Kilpatrick’s central interest in mathematics continued, and led him to return to Johns Hopkins in 1895. That experience, in contrast to his initial studies there, proved to be disappointing in most ways. Yet, during that time he took a variety of courses in philosophy, which provided another seminal experience that opened new areas of exploration. Together with his commitment to science, inquiry and clear thinking, his exposure to philosophical ideas and forms of reasoning was to have a direct bearing on his understanding of education and teaching.

Kilpatrick’s developing educational and philosophical ideas

After leaving Johns Hopkins for the second time, Kilpatrick in 1896 accepted the position of principal of the Anderson Elementary School in Savannah, Georgia. He taught the seventh grade and was responsible for supervising nine teachers and upwards of 400 students. At Anderson Elementary, Kilpatrick was able to extend his view that there should be no division between the student and the teacher—that is, that there should be a reciprocal relationship between the two—and that students should know that their teacher is their advocate. Such a relationship, Kilpatrick had thought for some time, was eroded by the practices of grading students and sending home report cards to their parents. As a result, he convinced the superintendent to make an exception to the usual evaluation activities that took place at the Anderson Elementary School; no report cards would be sent home to the parents of students in Mr. Kilpatrick’s classrooms. Parents did receive a note concerning their children’s absences and tardiness, but no evaluation of their classroom work per se.

Summarizing Kilpatrick’s orientation to teaching and to his students at the time, he said of his experiences at Anderson:

The important thing is for the teacher to understand each child, so he can give him recognition for the good things in him; and so to conduct his class that every child has an opportunity to show off those good things which he can and is able to do. I treated those children with a kind of affection. I never scolded them; I never used harshness or reproof. I tried to teach so that the children could get some good out of it and in such a way that they could see they were getting good out of it. I trusted my children. I appealed to the better in them. I respected them as persons and treated them as persons […] I appealed to the better in the children and I gave them an opportunity to act on that better self and then gave them recognition and approval for such behavior.

Rather than searching for a ‘system’ to manage and regulate student behaviour—what we now call a ‘classroom management’ orientation that typically regards students as requiring manipulation and control—Kilpatrick expected the best from his students, regarded them as people, recognized their accomplishments, and respected their interests while building on and enlarging their experiences.

Though he had planned to travel to Europe to study mathematics during the summer following his teaching at Anderson Elementary, the President of Mercer University told Kilpatrick that there was an opening for a professor of mathematics and astronomy at Mercer; Kilpatrick accepted an offer to fill that post, which began in 1897. While serving in that capacity, Kilpatrick met with prospective elementary school-teachers during weekly, voluntary meetings. For those meetings, Kilpatrick had his students read both Herbert Spencer and William James, among others. He also responded to students’ expressed interests by expanding the readings to include work on philosophy, using texts by such figures as Plato, René Descartes and David Hume. In general, during his teaching at Mercer, Kilpatrick lived out his desire for sustained, demanding work, and considered favourably the idea that such activities would provide the framework for his life. He studied the writings of Nicholas Murray 5 Butler, of Columbia University, and even had during this time a premonition that he would someday become the president of a major university.

At the end of his year on the faculty of Mercer, Kilpatrick enrolled in a summer school session at the University of Chicago. One of the courses he took during that summer of 1898 was offered by John Dewey. Contrary to what one might expect, Kilpatrick did not think highly of the teaching of Dewey in this course. As Kilpatrick later confided, regarding his initial interactions,

as I heard Dewey lecture, I thought of him as a very capable man. I honoured and respected him, but I failed to get from him the kind of leadership in thinking that I wished. Professor Dewey is not a good lecturer, and he does not always prepare the ground, so that a newcomer can follow him.

Kilpatrick’s feelings toward Dewey, of course, were not permanent. After studying and working with Dewey at Teachers College, Kilpatrick was to say that, ‘the work under Dewey remade my philosophy of life and education.’ and that as a philosopher Dewey is ‘next after Plato and Aristotle and above Kant and Hegel as a contributor to thought and life’. High praise indeed!

Kilpatrick’s studies with Charles DeGarmo, as part of a summer course in 1900 at Cornell University, were more inspirational that his first encounter with Dewey had been. Of DeGarmo’s book, Interest and effort, Kilpatrick remarked:

This book opened up a whole new world to me, as no book ever before. No other book had ever meant as much to me. I was stirred and moved. It coalesced all my feelings and aspirations; it showed me that there was no conflict between interest and effort; that they were not divergent forces but that they were inextricably allied; that effort follows interest. In other words, the more an individual becomes interested in something, the more effort he will put into it. Hence, the starting point in all education—the crux of the educational process—is individual interest; further, that the best and the richest kind of education starts with this self-propelled interest.

Building on his earlier ideas concerning children and the need for teachers to ‘get them on their side’, as well as to provide meaningful experiences and treat them as people with significant accomplishments, Kilpatrick saw the key role of interests in teaching. Students’ interests could change, be connected to related ideas and further interests, and developed with the aid of a sensitive, attentive teacher. Such ideas were to become central to his general educational philosophy and to his views and practices concerning teaching.

Agreeing to teach algebra and mathematics classes during a summer session at the University of Tennessee in 1906, Kilpatrick—true to his workaholic tendencies—audited two courses taught by faculty from Teachers College: Percival R. Cole and Edward L. Thorndike. The latter advised Kilpatrick during that summer session to apply for a scholarship from Teachers College. Kilpatrick took that advice and started out for Teachers College, in the fall of 1907, with a scholarship paying $250 per year. While a student there Kilpatrick was greatly influenced not only by John Dewey, but by such professors as Thorndike, the historian of education Paul Monroe, Frank McMurry, and Dean James E. Russell. At least as important, at Teachers College Kilpatrick became immersed in an institutional culture that embodied and furthered the zeal for education he had developed, and one that made the study of educational ideas and issues respectable. In short, Teachers College provided the sort of stimulating, theoretical and practical, diverse environment that had been lacking at Mercer University and even, at least for the most part, at Johns Hopkins. It was an environment that shaped Kilpatrick’s interests and substantially formed his life’s work.

Kilpatrick’s thought in maturity

Characteristic of Kilpatrick’s efforts to understand ideas and practices holistically, and to come to grips with their significance in social and political spheres, he came to think of philosophy as helping to form a generalized ‘point of view’ or ‘outlook on life.’ In his Philosophy of education, for example, Kilpatrick compares democratic with dictatorial points of view. He follows this by discussing the different educational agendas that follow from such basic political emphases.

The autocrat [Kilpatrick says] wishes docile followers […] Democracy wishes all the people to be both able and willing to judge wisely for themselves and for the common good as to the policies to be approved; it will accordingly seek a type of education to build responsible, thinking, public-spirited citizenship in all its people.

While the particular analysis of political ideas here is rather superficial, it demonstrates the commitment of the author to seeing educational practices, ideas and philosophies as integrated with larger, in this case political, contexts. It is these contexts that educators often fail to consider when they discuss the meaning of educational actions and decisions, and when they make educational choices regarding the school curriculum and classroom activities.

An avowed commitment to democratic values and principles fundamentally underlies Kilpatrick’s orientation to education and school practice. Like Dewey, Kilpatrick argued that the meaning of democracy extends far beyond issues and actions related to a government, and instead denotes a way of life that has both moral and personal consequences. For Kilpatrick, democracy,

means a way of life, a kind and quality of associated living in which sensitive moral principles assert the right to control individual and group conduct. It is worthy of note that […] democracy involves control, the control of both individual and group conduct for the good of all affected […] [this] control is internal, the demand of intelligence and conscience upon the individual himself to obey and serve the varied calls of a social morality […] [It is] always to allow expression of individuality as effectively as possible in all relationships.

Clearly, for Kilpatrick, a democratic society must impose a number of constraints and responsibilities on its citizens. While individualism is selfish and egocentric in its orientation, individuality is to be valued in part because it may serve the interests of social critique and social change. The responsibilities to maintain individuality but constrain individualism must be the special concern of educators, whose activities will either advance or thwart democratic ideas and actions. In a genuinely democratic society,

it is essential that both leaders and people have a clear philosophy of life and a clear philosophy of education. Any citizen then, who values democracy, who thinks much, feels deeply, and accepts responsibility for his acts will try to build a consistent and defensible outlook on life and on education. And the higher and finer the character the more likely will the person seek to build through the years a philosophy which has been thought out (so that he knows what values he stands for) and scrutinized for its defensibility (so that he knows how it affects the values of others).

Going beyond the realm of political principles and actions, we can think of education in even more expansive ways, Kilpatrick says. All people, perhaps as a part of what it means to be human, have points of view or attitudes, or operate—whether consciously or otherwise—with the aid of particular perspectives. What matters in the development of such perspectives is the forms of reasoning, and the specific reasons offered, that help us make decisions about educational policies and practices. A basic question here is how teachers and others are to decide among competing points of view, and how they are to develop a rational basis for choosing among such views. There are several ways we might make educational decisions. We can, when confronted with a range of options, rely on generally accepted customs or the received wisdom of our time. Or we can choose those options with which we are personally most comfortable, or that are least disruptive to our way of life and presuppositions. Yet such ‘choices’ are not the result of conscious, reflective deliberations, and therefore are not really choices at all. Such ways of determining one’s course of action are not philosophically defensible.

A more promising approach to making decisions in classrooms and other settings is to base them on the extent to which the resulting actions coincide with our expressed values. This, however, leaves aside the important prior question of what basis there is for justifying certain values rather than others, and substitutes instead a more or less technical orientation to making choices that is founded on consistency. The actions of a dictator may be consistent with his/her values, but they are not on that basis warranted. The process of making decisions itself can be critiqued, as when I ask myself if I have fully considered a comprehensive range of factors in making my decisions. Yet this approach, too, fails to consider the normative dimensions of both the choices we make and the actions which they promote and prohibit. In the final analysis, making decisions must, for Kilpatrick, be connected to the values my actions have, and ultimately based on such fundamental value questions as what constitutes the criteria for being good, doing good, etc. These are the very questions with which philosophy is concerned. Thus philosophy, and a philosophy of education, leads us to examine not only our values, but to search for more adequate values that can be examined and, if not ‘proven,’ at least rationally defended. The ‘stubborn search for more and more adequate’ values is what Kilpatrick identifies as philosophizing.

Such a conception of philosophy makes clear its essential role for teachers. A comprehensive philosophy of education should not only help us think through abstract issues and questions, but also help us make decisions about both general educational policies and specific school practices. In this understanding of philosophy, it amounts to something like a self-conscious, rationally defensible, orienting point of view that affects what people think and value, and how they act, in day-to-day situations and in all social institutions—including schools. Philosophy is thus associated with a range of possible outlooks or orientations, and is inherently connected to a range of political ideas and platforms. As Kilpatrick put this point:

(i) any distinctive social-political outlook, as democracy or Hitlerism or Communism or reactionary conservatism, will wish its own kind of education to perpetuate its kind of life; and (ii) each distinctive kind of teaching-learning procedure will, even if the teacher does not know it, make for its own definite kind of social life […] [As a result,] school people—teachers, superintendents, supervisors—must ask themselves very seriously (i) what kind of social outlook their school management and teaching tends to support; (ii) what kind of social life they ought to support; and (iii) what kind of school management and teaching-learning procedures they ought to adopt in order to support this desired social life.

In Kilpatrick’s view, teachers and others involved with schools must have some perspective, some point of view that grows out of the development of a philosophy of one sort or another, which can serve to ground the various choices they must make. Contrast this to a common contemporary perspective according to which what matters most for teachers and prospective teachers is ‘what works’ in classrooms, often understood as whatever maintains classroom decorum, raises students’ standardized test scores, meets the standards of state and national accreditation and licensing agencies, or simply fits with accepted practices or the dominant culture of schooling. Asking teachers to become philosophers, Kilpatrick sees teaching as a social and political undertaking that requires our deepest, most comprehensive, clearest thinking.

This orientation to philosophy, obviously, is not to be equated with abstract metaphysical speculation or analyses that are removed from day to day life. Indeed, the activities associated with everyday living provide the arena for philosophical questioning and analysis, with the goal of leading a better life, having fuller experiences, and developing one’s capacities for further growth. Such views are central to the pragmatic tradition that William James, Charles S. Peirce, John Dewey, and others articulated and that is still influential in contemporary educational debates. In looking at Kilpatrick’s views on what he calls ‘the life process’ and its relationship to philosophy, we can see the ways that The origin of species, discovered at Johns Hopkins, and modern science generally, are related to this pragmatic orientation.

As noted already, Darwin’s book in some ways undermined older humanist traditions that focused on realities that were assumed to be changeless and eternal. With the publication of The origin of species, change became the basic fact of biological and social life. Such a perspective affected people’s conception of knowledge, as well as their views on ethical and political practices. Two implications of this change are especially important for understanding Kilpatrick’s views on education. One is that change is the constant, in individual and social life—something to be expected and anticipated, even prized, rather than viewed as symptomatic of some inadequacy and avoided. A second implication of the new scientific outlook is that action or behaviour within an environment becomes the key for the study of the ‘life process’ for both individuals and groups.

For Kilpatrick, an active, satisfying life involves striving, desiring, acting, or more generally what he calls ‘purposing’. He emphasizes the importance of ‘behaving’, which for Kilpatrick has a much different meaning than the ideas associated with behaviourism. Consistent with his earlier fascination with the ideas of Charles DeGarmo regarding effort and interest, Kilpatrick says that behaving involves the response of an organism to a situation. That response often elicits ‘wants’ or desires that in turn create an aim or goal, followed by efforts to realize that aim. In the process of attaining that aim, people develop related interests and experience positive enjoyment. The key to understanding the ‘life process’ is thus to be found in effort and interest, followed by further interest. In other words, the life process of human beings is intimately connected to interactions with social and physical environments in which our interest is peaked, resulting in the creation of desires from which we articulate an aim that is pursued. The life process is, hence, essentially interactive and social. The ‘true unit of study’ as Kilpatrick puts it, is ‘the organism-in-active-interaction-with-the-environment’.

It is within this context that we may understand more fully Kilpatrick’s project method, as well as its justification. What is crucial within the project method is that there be some dominating purpose—which of course may not be observable—in which students wholeheartedly participate. Consider a boy who wishes to make a kite:

the purpose is the inner urge that carries the boy on in the face of hindrance and difficulty. It brings readiness to pertinent inner resources of knowledge and thought. Eye and hand are made alert. The purpose acting as aim guides the boy’s thinking, directs his examination of plan and material, elicits from within appropriate suggestions, and tests these several suggestions by their pertinence to the end in view. The purpose in that it contemplates a specific end defines success: the kite must fly or he has failed. The progressive attaining of success with reference to subordinate aims brings satisfaction at the successive stages of completion […] The purpose thus supplies the motive power, makes available inner resources, guides the process to its preconceived end, and by this satisfactory success fixes in the boy’s mind and character the successful steps as part and parcel of one whole.

The project method, in unifying students’ interests with action in the world and emphasizing ‘the hearty purposeful act’, provides one example of the way in which ‘education’ and ‘life’, 9 knowing and doing, are continuous. Beyond this, the ability and determination to engage the world through such acts allows people to control their lives, and to act with care in bringing to fruition worthy activities; these traits, in turn, allow people to exercise their moral responsibility. Such a person, Kilpatrick remarks, ‘presents the ideal of democratic citizenship’.

Modern science, in dispelling the notion that there are invariant ‘essences’ that are central to understanding the nature of the universe, provided additional grounds for supporting the view that people must be seen in context, as well as grounds for valuing acts of purposing that are central to moral undertakings and citizenship. In promoting an interactive view of the universe according to which ‘being’ and ‘environment’ are two sides of the same coin, interconnected and mutually influential, we allow for people’s actions in that world changing both ourselves and the larger world. While Kilpatrick mentions the technological advances made possible by modern science, he clearly thinks its cultural implications are more important, helping develop new outlooks on life and how we think, feel and act as a result. An interactive orientation leads to a new humanism with people rather than abstract essences at the centre, with a view toward the intelligent direction of affairs. Such intelligent direction was especially needed during the time Kilpatrick was writing many of his treatises, given the economic, military and social crises in which the United States of America was engulfed or that were about to develop.

Human activity in this view must be understood as actions-in-context, as enmeshed in environments that both affect, and are affected by, our actions. Among other things, this view denies the existence of autonomous individuals whose ‘nature’ is fixed and unalterable. The importance of the context of experience also runs counter to the deeply held assumption of ‘radical individualism’ that has been a central feature of Western industrialized nations.31 Such a focus on individualism, Kilpatrick reminds us, is also inconsistent with the requirements for democracy. As he puts it:

the essence of democracy is to be concerned about each individual and his welfare. This is regard for individuality or personality, not a belief in individualism. In individualism there is too much of each man for himself regardless of others, or even at the expense of others. Such an attitude true democracy cannot accept. On the contrary, democracy will test each social institution and program by whether in its working it makes for the welfare and happiness of each one of everybody, all together, on terms of substantial equality.

The meanings of progressivism

By the time Kilpatrick retired from Teachers College in 1938, his ideas and activities had been widely discussed among academics and school-teachers. Kilpatrick continued to enjoy a reputation as a first-rate teacher and was therefore beloved by his students. As Herbert M. Kliebard has remarked, Kilpatrick became ‘the most popular professor in Teachers College history’.

Further testimony to the depth of his educational commitments can be seen in the fact that Kilpatrick helped found Bennington College in Vermont, and served on its Board of Trustees for seven years. His social commitments are reflected in his Presidency of the New York Urban League from 1941 to 1951.

The educational ideas and orientations of Kilpatrick continued to be timely, even after his death on 13 February 1965, in New York City. A special issue of Educational theory was dedicated to Kilpatrick shortly thereafter in which several of his colleagues wrote movingly about both the man and his ideas.34 Kilpatrick’s personal love for teaching and the depth and popularity of his ideas concerning educational matters continue to be worth pondering. But his personal appeal and his particular agenda for American education are only part of the story.

What Kilpatrick makes clear is the depth of inquiry and the dedication to clear thinking that are necessary for all those concerned with educational matters. In addition, Kilpatrick’s ideas—along with Dewey, and a host of others, now and then—continue to offer educational alternatives to the emphases on efficiency, standardization, control and manipulation. He offered a way to make learning and living really unified, and to change the nature of public school classrooms.

In recognizing the need for philosophical reasoning and reflection, and for underlining the political purposes and possibilities of education, Kilpatrick’s ideas also continue to be pertinent. This is especially relevant for discussions that have taken place in the last few years, as many have struggled to conceptualize democratic life, the democratic purposes of schooling, and the need to link those purposes with social and moral actions.

Discussions regarding the possible role of United States schools in promoting a democratic social order are as old as attempts to establish a system of publicly supported education. From Thomas Jefferson’s proposals for a system of schools in Virginia, to Horace Mann’s call for school reform in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, to the report of the National Commission on Excellence in Education, to the recent recommendations of the Eisenhower Leadership Group, America’s schools have been called upon to advance a variety of purportedly democratic purposes.

One problem—both conceptual and ideological—that has repeatedly plagued discussions about schooling and democracy is that the meaning of democratic discourse, practice and values continues to undergo substantial, periodic revision. Curricular changes have, in fact, been initiated in an attempt to clarify or change the meaning of democratic life and the social and political choices that are consistent with it. Certainly Kilpatrick’s ideas fit within such efforts at change.

Beyond the considerations outlined by Kilpatrick in this regard, a variety of contemporary interest groups and those in positions of power have suggested one vision of democracy or another that is consistent with their larger ideological agenda. Powerful segments of United States society affiliated with what has been called ‘the conservative restoration’37 and the ‘Republican revolution’ are attempting to reassert an agenda that caricatures or simply denies the existence of those progressive strands of democratic thought and practice which they oppose. Clearly, important conceptual and ideological differences exist among those urging that we adopt or invigorate democratic practices, values, and institutions. Understanding these differences is crucial if we are to articulate a vision of social possibility for schools. For making this point abundantly clear, we have a serious debt to Kilpatrick and other student-centered progressives.

Kilpatrick is insightful in clarifying how daily classroom decisions carry political import and meaning. As he makes clear, questions and issues regarding pedagogy and curriculum intersect with the political, moral and social domains of our worlds. Educational choices frequently respond to, and help reinforce, some set of values, priorities and perspectives that have the effect of furthering some interests while hampering others. Teachers as a result confront several difficult, complex issues: What values should guide the establishment of some kind of classroom climate? What modes of analysis, ways of thinking and kinds of experiences should be encouraged, which hampered? What attitudes and expectations should be encouraged or altered among students? What modes of interaction should be promoted or curtailed in the classroom? What forms of knowledge are most worth perpetuating? In short, for teachers there is no neutral place to stand, as decisions that are made every day in classrooms—or, just as likely, made by others outside classrooms—support certain normative beliefs and assumptions, ideals and convictions. Such beliefs and assumptions must, as Kilpatrick says, be critically scrutinized and analyzed by teachers, and by those preparing to teach.

The normative dimensions of education differentiate teaching from most other professions. Even when their autonomy is constricted, teachers can influence the students in their care, and those students’ futures, in ways that speak in the broadest sense to the political nature of teaching and schooling. In addition to ‘providing a service’ to the public, and beyond an obsession with ‘the bottom line’ that currently infects both the ‘private sector’ and an increasingly privatized neo-public one, teachers affect the hopes, dreams, attitudes, and perspectives of their students, and because of that the future of the society in which they and their students live.

In this context, Kilpatrick’s insistence that democracy is larger than the actions of government is critically important. In his words, democracy ‘means a way of life, a kind and quality of associated living in which sensitive moral principles assert the right to control individual and group conduct’. Democracy provides a moral and broadly social framework that has implications for interpersonal as well as institutional actions and decisions that must be made on a day-to-day basis. The way we live with each other, the way we treat one another in our daily interactions and relationships, is central to this understanding of democracy and its implications. Thinking about democracy as only a way of making electoral choices or instituting governmental policies allows undemocratic practices like those associated with inegalitarian economic and cultural practices seem outside the pale of democratic inquiry—as if a democratic critique of economic and cultural realities involves making something like a category mistake.

Beyond the crucial need for clear thinking, reasons for choices and action, philosophical acuity, and purposeful, wholehearted activities tied to interests, any sort of wideranging participatory democracy is only possible if we reinvigorate a sense of community. This in turn requires, and is supported by, a grasp of the possibilities for a common good, collectively decided by people engaged in open, moral discourse with others, within which a commitment to equality is central. We need a broadly based cultural vision for democratic practice in which daily activities and interactions, a search for the common good, the reinvigoration of community, and an openness to dissent and difference, mutually support each other, and allow for new forms of life and decision making to emerge.

A democratic community must, finally, enable people to develop values and ideas that outline alternative social possibilities. Equally important, such a community must generate concrete practices that enact a moral vision—a vision not reducible to any set of present realities and yet not simply an ‘idealist’ construction.

A democratic community encourages its members to become participants in civic discussions that require concerted, collaborative actions in the name of social justice and structural change. Kilpatrick, like Dewey, understood knowledge to be the outcome of past and present human efforts to come to terms with the worlds in which we live. For progressives generally, as can be seen in Kilpatrick’s ‘project method’, children are people who are, and ought to be, actively engaged in attempts to understand and become more skilful in the world in which they live. What is inadequately emphasized by many progressives, including Kilpatrick, is an articulated direction in which this educational endeavour should head. Early on, Counts criticized the progressive movement as lacking this sense of direction:

If an educational movement, or any other movement, calls itself progressive, it must have orientation; it must possess direction. The work itself implies moving forward, and moving forward can have little meaning in the absence of clearly defined purposes […] Here, I think, we find the fundamental weakness, not only of Progressive Education, but also of American education generally. Like a baby shaking a rattle, we seem to be utterly content with action, provided it is sufficiently vigorous and noisy […] The weakness of Progressive Education thus lies in the fact that it has elaborated no theory of social welfare […] In this, of course, it is but reflecting the viewpoint of the members of the liberal-minded upper middle class who send their children to the Progressive schools—persons who are fairly well-off […] who pride themselves on their open-mindedness and tolerance, who favor in a mild sort of way fairly liberal programs of social reconstruction, who are full of good will and humane sentiment […] who are genuinely distressed at the sight of unwanted forms of cruelty, misery and suffering […] but who, in spite of all their good qualities, have no deep and abiding loyalties, possess no convictions for which they would sacrifice over-much […] are rather insensitive to the accepted forms of social injustice, [and] are content to play the role of interested spectator in the drama of human history.

When we add a more encompassing and fleshed out societal context to a progressive educational agenda, and a set of moral, political and cultural values that provides the direction Counts advocated, we have a more encompassing basis for articulating a direction for education.

This direction builds on the ideas of Kilpatrick and yet, in some important ways, goes beyond them. It is guided by a commitment to radical democracy as it may provide avenues for reconceiving social institutions and practices, guided by a populism in form, and dedicated to structural change. Such change may be brought about by a reinvigoration of communities in which genuine participation, moral discourse and the common good fuel actions in the world. Seeing the various components of our worlds as susceptible to alteration through collaborative actions that build on our sociability; articulating moral values in open settings in which dissent is expected and valued that can guide those actions; and altering hierarchical structures and inequalities that demean and disempower, and that deny liberty and opportunity, form basic elements of an enlarged progressive direction.

In this vision we bring together the child, the curriculum and the society. It is consistent with the emphasis on a progressive democracy founded on participation, moral reasoning, social justice and action in and on the world. It provides hope for those now harmed by the inequalities that continue to thrive and grow in the United States. It also offers hope for significant change in society and in classrooms where democratic values may be enacted.

For pointing to the need for educators to see their actions as embedded in, and helping further, social, political and philosophical perspectives, we owe much both to William Heard Kilpatrick and to the progressive tradition in which he was so influential. Especially in schools, where it is still all too common for students’ interests to be squashed and their accomplishments ignored, the advice to get students and teacher ‘on the same side,’ and to create classroom environments within which the joys of genuine exploration can be felt, is critically important. To accomplish this, and to help create a social context of the sort that will allow the student to participate in similar ways as an adult, requires progressive political action of a somewhat more directed, encompassing sort. That action must be more attuned to the particular dynamics of the sort of society we have, and productive of a vision of what a better society would look like. How to get from the one to the other, and what that process implies for schooling and teaching, is perhaps the fundamental problem that must be confronted by contemporary educators who are committed to a new progressivism.

Notes

- Landon E. Beyer (United States of America) Associate Dean for Teacher Education at Indiana University, Bloomington. His interests include developing alternative approaches to teacher education, curriculum theory and development, the social foundations of education, and the arts and aesthetics. His most recent publications include: Creating democratic classrooms: the struggle to integrate theory and practice (1996); Curriculum in conflict: 13 social visions, educational agendas, and progressive school reform (1996) (with Daniel P. Liston); and The curriculum: problems, politics, and possibilities, (second ed., in press) (with Michael W. Apple). He is currently working on books dealing with teaching and schooling, and the role and significance of popular culture in society and classrooms.

- See William H. Kilpatrick, The project method, Teachers college record (New York), vol. XIX, no. 4, September 1918, p. 319–35. For an early example of the project method as used in the public schools, see Ellsworth Collings, An experiment with a project curriculum, New York, The Macmillan Company, 1923.

- Samuel Tenenbaum, William Heard Kilpatrick: trail blazer in education, p. 4, New York, Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1951.

- Ibid., p. 5.

- Ibid., p. 6.

- Charles Darwin, On the origin of species by means of natural selection, New York, Appleton, 1887.

- Tenenbaum, op. cit., p. 13.

- Ibid., p. 14.

- Ibid., p. 15.

- For example, see John Franklin Bobbitt, Some general principles of management applied to the problems of city-school systems, Twelfth yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, Part I, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1913; and The curriculum, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1913; Edward L. Thorndike, The psychology of wants, interests, and attitudes, New York, AppletonCentury Crofts, 1935; W.W. Charters, Job analysis and the training of teachers, Journal of education research (Washington, DC), vol. 10, 1924; and Curriculum construction, New York: Macmillan, 1927; and David Snedden, Sociological determination of objectives in education, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1921. An incisive critique of these movements is found in William Heard Kilpatrick, Remaking the curriculum, New York, Newson & Company, 1936.

- Tenenbaum, op. cit., p. 23.

- Ibid., p. 26.

- Ibid., p. 31.

- See Landon E. Beyer, Uncontrolled students eventually become unmanageable: classroom discipline in political perspective, in: Ronald E. Butchart and Barbara McEwan, eds., The democratic and emancipatory potential of public education, Albany, New York, State University of New York Press, in press.

- Tenenbaum, op. cit., p. 37.

- From Kilpatrick’s diary entry of 18 March 1935, as quoted in Tenenbaum, op. cit., p. 75.

- Charles DeGarmo, Interest and education: the doctrine of interest and its concrete application, New York, Macmillan, 1903.

- Tenenbaum, op. cit., p. 37.

- William Heard Kilpatrick, Philosophy of education, New York, The Macmillan Company, 1951.

- Ibid., p. 5.

- Ibid., p. 127.

- Ibid., p. 6.

- Ibid., p. 9.

- For an interesting contemporary treatment of the role of philosophy in education that has some affinity with Kilpatrick’s position, see Tony W. Johnson, Discipleship or pilgrimage: the educator’s quest for philosophy, Albany, State University of New York Press, 1995.

- Kilpatrick, Philosophy of education, op. cit., p. 11–12.

- For contemporary approaches to education and teaching that suggest similar emphases, see Johnson, op. cit., and Landon E. Beyer, Knowing and acting: inquiry, ideology, and educational studies, London, Falmer Press, 1988.

- See, for example, Herbert M. Kliebard, The struggle for the american curriculum, 1893–1958, New York, Routledge, 1986; Cleo H. Cherryholmes, Power and criticism: poststructural investigations in education, New York, Teachers College Press, 1988; Jim Garrison, The new scholarship on Dewey, Boston, Kluwer Academic, 1995; Brian Patrick Hendley, Dewey, Russell, Whitehead: philosophers as educators, Carbondale, IL, Southern Illinois University Press, 1986; and Harriet K. Cuffaro, Experimenting with the world: John Dewey and the early childhood classroom, New York, Teachers College Press, 1995.

- Kilpatrick, Philosophy of education, op. cit., p. 14.

- Kilpatrick, The project method, op. cit., p. 325. 14

- Ibid., p. 322.

- See Robert N. Bellah, Richard R. Madsen, William M. Sullivan, Ann Swidler and Steven M. Tipton, Habits of the heart: individualism and commitment in American life, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press, 1985; and Steven Lukes, Individualism, New York, Harper & Row, 1973.

- William H. Kilpatrick, Introduction: the underlying philosophy of coöperative activities for community improvement, in: Paul R. Hanna, Youth serves the community, p. 3–4, New York, D. Appleton-Century Company, 1936. For a discussion of the incompatibility of classical liberal individualism and democracy, and of the contradictions between democracy and capitalism, see Landon E. Beyer and Daniel P. Liston, Curriculum in conflict: social visions, educational agendas, and progressive school reform, New York, Teachers College Press, 1996.

- Kliebard, op. cit., p. 159.

- See Educational theory (Champaign, IL), vol. 16, no. 1, January 1966.

- See, for example, Benjamin Barber, Strong democracy, Berkeley, CA, University of California Press, 1984; and An aristocracy of everyone: the politics of education and the future of America, New York, Ballantine Books, 1992; Samuel Bowles & Herbert Gintis, Democracy & capitalism: property, community, and the contradictions of modern social thought, New York, Basic Books, 1987; Jean Bethke Elshtain, Democracy on trial, New York, Basic Books, 1995; Ann Bastian, et al., Choosing equality: the case for democratic schooling, Philadelphia, PA, Temple University Press, 1985; Amy Gutmann, Democratic education, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1987; and Landon E. Beyer, Creating democratic classrooms: the struggle to integrate theory and practice, New York, Teacher College Press, 1996; and Michael W. Apple and James A. Beane, Democratic schools, Washington, DC, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 1995.

- See Gordon C. Lee, Crusade against ignorance: Thomas Jefferson on education, New York, Teachers College Press, 1991; National Commission on Excellence in Education, A nation at risk: the imperative for educational reform, Washington, DC, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1983; Eisenhower Leadership Group, Democracy at risk: how schools can lead, College Park, MD, Center for Political Leadership & Participation, May 1996.

- See Michael W. Apple, Official knowledge: democratic education in a conservative age, New York, Routledge, 1993.

- Kilpatrick, Philosophy of education, op. cit., p. 127.

- George S. Counts, Dare the schools build a new social order?, New York, The John Day Company, 1932, p. 4–5.

Works by William Heard Kilpatrick

- The Montessori system examined. New York, Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Froebel’s kindergarten principles critically examined. New York, Macmillan.

- Source book in the philosophy of education. New York, Macmillan.

- Foundations of method: informal talks on teaching. New York, Macmillan.

- Education for a changing civilization. New York, Macmillan.

- Education and social crisis: a proposed program. New York, Liveright, Inc.

- The educational frontier ( in collaboration with others). Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press.

- A reconstructed theory of the educative process. New York, Bureau of Publications, Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Remaking the curriculum. New York, Newson & Company.

- Group education for a democracy. New York, American Association for the Study of Group Work.

- Selfhood and civilization: a study of the self-other process. New York, Macmillan, 1941.

- Intercultural attitudes in the making: parents, youth leaders, and teachers at work. New York, Harper, 1947.

- Modern education and better human relations. New York, Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith.

- Modern education: its proper work. New York, John Dewey Society.

- Philosophy of education. New York, Macmillan

Copyright notice

This text was originally published by PROSPECTS: the quarterly review of comparative education (Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education), vol. XXVII, no. 3, September 1997, p. 470-85.

Reproduced with permission. Read the PDF version of the article here.

Photo source: Georgia College